It’s 7am in a trailer park in Clinton, Missouri. Photographer Ingetje Tadros stands amidst the detritus of broken televisions, discarded furniture and rusting cars that are features of the park’s unkempt landscape. Dogs are barking hysterically. Suddenly a trailer door swings open spilling light into the gloom silhouetting a man in his early twenties. “Shut the fuck up!” he screams. Tadros catches his eye. “Who are you?” he snarls. “Who are you?” she replies boldly in English that is heavily laced with her native Dutch accent. She steps forward and introduces herself.

This was how Tadros started her first day at the 63rd Missouri Photo Workshop in 2011, which is renowned for its high standards and tough love. But there is little that unnerves Tadros, particularly when she is focused on getting the story, which is just as well as much of her documentary work centres on confronting subjects that involve minority groups and social injustice.

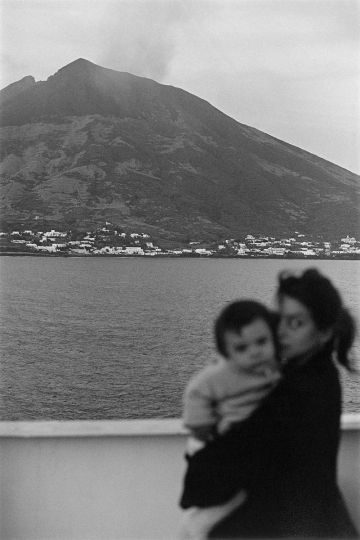

Since her teen years Dutch-born Tadros has taken photographs. In the early days she travelled extensively, and her particular interest was tribal communities in Africa. But she didn’t confine herself to that continent, and over the decades she’s travelled to more than 55 countries. It has only been in the last few years that she’s turned her focus to photojournalism throwing herself in the deep end and her trajectory has been nothing short of stellar.

In 2015 Tadros went to Visa Pour L’Image to promote ‘This is My Country’ her in-depth documentation of Kennedy Hill, an Aboriginal community in Broome, Western Australia. She came away with a book deal with FotoEvidence, as well as interest from magazines such as Stern, which recently ran a major spread. In 2015 she won the Nikon-Walkley Feature/Photographic Essay Award for the same body of work, which was on show at this year’s Head On Photo Festival in Sydney. At Visa Pour L’Image this year she took out the ANI Award and ‘This is My Country’ is also part of the projections at Angkor Photo Festival in Cambodia in December.

But this isn’t a story just about good fortune or being in the right place at the right time. It is a story about one woman’s dogged determination to be the best photographer she can be and the lengths she has gone to do that.

For the past four years Tadros, who lives in Broome with her husband where they run a restaurant, has focused on documenting the lives of the indigenous community at Kennedy Hill. But before she got to the point of turning her camera on her own backyard, Tadros attended numerous workshops around the world honing her skills including the aforementioned Missouri workshop.

“That was really tough,” says Tadros of her week in Clinton, Missouri. “In two days you have to come up with three stories, your main one and two back ups. And you can’t start on your story until the lecturer approves it. There’s a population of 10,000 and there’s 64 photographers running around trying to get stories so you can imagine it was crazy!”

Not to be outdone, Tadros decided to go to the “worst part of town” and that’s how she ended up in the trailer park. When she saw the man open the door of the trailer and yell at the dogs she thought, “that’s my boy! I told him what I was doing and said, honestly I can’t say why but I feel you are an interesting subject. So we started talking and he was the same age as my son and somehow we connected.” Tadros discovered he lived in the trailer with his wife and baby. She asked him to run the idea by his partner and said she’d be back.

By the time classes started that morning Tadros had her three stories lined up. When she pitched the trailer park story as her primary choice the lecturer said it was too hard. “He told me I needed permission from the wife also, so I went back. She was really nice and young. You know I’m a mother so I can relate to that age. I told them I had to stalk them for four days and wasn’t allowed to direct them. I was just going to document their lives, so if they sat around doing nothing that’s what I was going to photograph. And they agreed. So I went back and the lecturer said, no we can’t give you permission, it is going to be too hard for you. I got really shitty with them, I didn’t know debating the idea was part of the lesson,” she laughs at the memory. “They let me talk for about ten minutes, and I was arguing with them about why this was a good subject, what I could see happening with the story, and then they said okay you can do it. So it was like a test!”

Since that time Tadros has created numerous self-funded projects that focus on confronting, humanist themes including mental health in Bali, where she shot a photo essay on caged humans during her second Momenta workshop, a story that was picked up by the media, published widely and also exhibited in Asia.

While she isn’t driven by the need to make a living out of her photojournalism Tadros does work as a stringer for various agencies and newspapers mostly working on local stories. In recent years there’s been plenty happening in Broome and Tadros has been busy, but she says, “I don’t want to do it for the money, I really want to do it for pleasure, to learn and to also raise awareness. I know I am very privileged”.

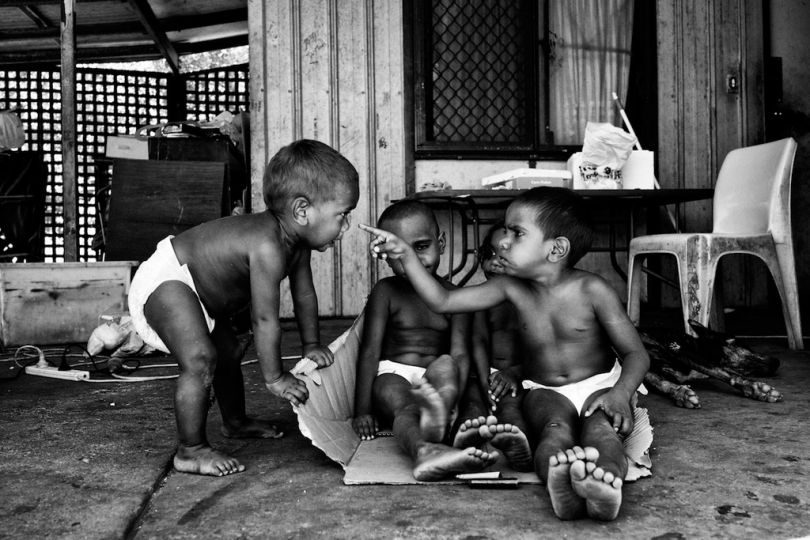

It is this desire to raise awareness around stories that are seldom told, and rarely get mainstream media coverage, that led Tadros to look at her own backyard and the indigenous community at Kennedy Hill. “Have you ever walked into a really dysfunctional Aboriginal community? “ she asks. “It’s really, really full on, but I’m a strong woman. I walked in and asked them who was the boss. I talked to them about what I’d been doing and what I wanted to do and slowly I built up a rapport and relationship. I had to learn the body language and how to deal with the women who are very strong and also with the men. You have to be aware of your environment and take it slowly”. There have only been a couple of times when she’s felt the vibe was too heavy for her to stay.

“You know in the community there’s binge drinking and it’s full on and often the music is very loud. I speak really rough with them, but I always stay on the same level or go lower and sit in the shit, I don’t care. I asked them one time ‘how come you always let me in?’ They said, ‘last week there was this guy with a big lens at the fence and he was making photos over the fence and we chased him all the way back to his car. We don’t chase you because you always sit with us and you always ask to make photos.”

As the months became years Tadros built an amazing library of images that captured life at Kennedy Hill, the good and the bad. The more she integrated, the greater the access and community members began to allow her to photograph many personal moments. “I don’t use all the photos in my work, it is important to give back and they don’t have nice photos of their families and kids, so it’s wonderful to help in that way. I always give them prints”.

In the past year her work has become even more political as the Western Australian government has earmarked Kennedy Hill for closure as federal funding has been withdrawn. A few of the houses have already been condemned and fenced off and Tadros says what’s happening at Kennedy Hill is indicative of what is happening with tribal people all over the world.

“By closing communities, ancient knowledge that has been passed down through generations will get lost and people will be lost because of this disconnection (to the land) that nurtures them physically, emotionally and spiritually,” says Tadros. “That’s my drive, to draw attention to what’s happening. I’ve always wanted to do something with tribal people and the Aboriginals are tribal. I live in their backyard.”

The Kennedy Hill work is shot in black and white, which Tadros says was a conscious choice as the beauty of the landscape around Broome can be distracting and she wants the audience to focus on the people in her pictures. And every picture tells a unique story made possible through the access that Tadros has, access that comes through an extraordinary investment in time and the building of trust with each member of the community.

Even though she has a solid body of work now on Kennedy Hill, the story isn’t over for Tadros who still visits the community almost everyday when she’s in Broome. Her most recent photographs are of squatters from the bush who have come into town from desert communities that are dry or from cattle stations. “They told me come and we’ll cook damper for you. Come at 4am! So I got up early, brought flour and eggs with me and took some beautiful images of them making damper”.

Alison Stieven-Taylor

Ingetje Tadros, This is my country

Published by FotoEvidence

$100 (signed copy)