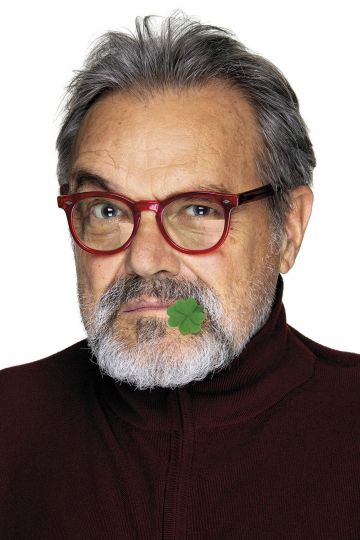

Oliviero Toscani passed away yesterday. Today’s edition is entirely dedicated to him, made from a selection from our Archives. Paola Sammartano, our correspondant in Italy knew Oliviero. After receiving the sad news, she wrote this text for The Eye of Photography:

He was foolish, in the positive sense of the word: as someone who challenges conventions, who sees further. Stubborn and able to anticipate issues and problems in society, he confronted it (and all of us) with powerful images, so disruptive and disturbing that they forced us all to think.

He challenged, often contested, controversial aspects that society tended to keep under wraps. He slammed them on the front pages (of the best-known and most popular fashion magazines and newspapers) and on those large billboards we used to see in our cities – they were so huge, they pierced the urban landscape so strongly – forcing us to take note of highly uncomfortable issues that were peculiar to those years and yet to our own.

He did so in a way that involved, monopolising the sense of sight, at a time when we were not yet in the presence of that “fury of images” (according to Joan Fontcuberta’s definition) that grips us today. At the same time, they were a very effective tool, a language, a technique to break indifference.

He did this by creating these photographs for advertising (his creative adventure and collaboration with Benetton lasted almost twenty years), breaking the rules of the advertising image. He replaced the glamour with irreverence and provocation. Social criticism photography was communicated through fashion: its channels were reaching a vast audience, always in search of different and new points of view, far from stereotypes and conventions.

This is how irreverent campaigns were born, designed to sell products, but also to convey messages.

Such as those for Jesus and Benetton (to name a few of the brands he has worked with). They are campaigns that also provoke debate, often bringing to light dramas such as anorexia, AIDS, the fight for human rights, against racial discrimination: think of the campaign for the brand Nolita, whose protagonist was the French actress and model Isabelle Caro; Sentenced to Death (2000) or the breastfeeding woman (1989). Or the 1996 campaign, for United Colors of Benetton, featuring three (human) hearts with the inscription White, Black, Yellow, demonstrating that we are all equal.

His portraits of personalities who ‘changed the world’, such as Mick Jagger, Lou Reed, Carmelo Bene, Federico Fellini and the great protagonists of culture from the 1970s and beyond, also point in this direction.

The same goes for his projects on the survivors of the massacre of Sant’Anna di Stazzema, the Nuovo Paesaggio Italiano or the Razza Umana, with over 10,000 portraits collected by travelling around the world with an itinerant studio (a bit like the photographers of the 19th century) taking pictures of whoever was available. It’s perhaps the largest existing archive on the morphological and social differences of humanity, an archive whose summa, in fact, leads to the uniqueness of the human being through the coexistence of differences.

Communicating was one of his missions: he was one of the founders of the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio, taught visual communication in various university faculties and wrote books on communication. In the 1990s he came up with something way that was far ahead of his time, such as Colors (from 1990), the world’s first global magazine, and he conceived and directed Fabrica, a research centre for creativity in modern communication and a point of reference for youth culture in the 1990s.

The most recent exhibition dedicated to him and his work is ‘Oliviero Toscani: photography and provocation’, which ended a few days ago at the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, with vintage prints that Oliviero has selected from his archive and new stories to discover. He wanted to be there for the opening.

I met Oliviero many years ago, when I was a young journalist, talking with him about photographs of horses (his beloved Appaloosas) and wolves (the one in an ad for Benetton). Then I talked with him more times about photography. Now, at the age of 82, he passed away, leaving behind, I believe, a legacy to young photographers and all those who use the language of images, the idea of the importance of the message in breaking down indifference, of the power of photography to force us to see, to take note of what is wrong and, if possible, to put it right. And the fact that our strength lies in imagination, which is freedom and the engine for creativity and commitment. That’s a human power that no computer can match.

Paola Sammartano

Paola Sammartano is a journalist specialized in arts and photography based in Milan, Italy.