Stephen Dater Gallery reported the passing of Marvin E. Newman in those words:

We are so sad to report that gallery artist, and long-time friend, Marvin E. Newman, has passed away at the age of 95. Marvin was one of only a few photographers who attended both the Photo League in NY and the Institute of Design, Chicago. He was the first graduate to obtain a master’s degree in photography from the ID. He was one of the most influential mid-century humanist photographers, and went on to be one of the great sports photographers. – Stephen Dater Gallery

Back in 2018, we published the following article by Lyle Rexer.

Marvin Newman : A taste for modernity

Marvin Newman, the storyteller, Marvin Newman the inventor. Marvin Newman, the charmer. At the age of ninety, with a mischievous glint in his eye, Marvin E. Newman casually drops a thousand tales that tell the story of American photography from the end of the Second World War to the present day. He’s an inquisitive man who embraces the world and never takes himself too seriously. He has photographed everything with great enthusiasm: from street reporting to advertising and sports, from night life to high fashion. The gallery Les Douches, in Paris, is offering him an exhibition.

In career terms, photography is an odd game, perhaps the oddest there is. The artist and the working professional employ the same device (a camera), make similar decisions (framing, lighting, lenses, point of view), and confront the same need to bend the medium to their intentions—to find ways to make a picture that hasn’t been seen before. Yet the artist is supposed to pursue self-expression, while the professional is all about fulfilling the assignment. Marvin Newman never accepted the division. He once remarked, “No matter what I shoot, I always photograph for myself.” It explains why, among American photographers, he has made innovative work in surprising places.

The model of the working photographer, Newman has shot almost every kind of commercial and professional photograph there is, from reportage and advertising to street photography and sports — indelible images, in the classic sense, of the streets of Chicago, the nightlife of Las Vegas, and Inuit ceremonies in Alaska. He even shot fashion, and in the magazine’s heyday, Playboy bought his photographs.

At the same time, his work has also been included in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the International Center of Photography, and many galleries, including Roy DeCarava’s legendary A Photographer’s Gallery. Two decades before conceptual photography made its appearance in the United States, Newman created serial images that dealt with photographic representation as theme and variation. But the very diversity of Newman’s work and the fact that so much of it appeared in popular magazines, including several that no longer exist, also explain why it has taken until now for his photographs to be recognized as a singular oeuvre and for Newman himself to be acknowledged as a major American postwar photographer.

One person who also believed that photography is one tree with many branches was the artist who would have a profound influence on Newman, even though he never met him. Émigré László Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which later became the Institute of Design, where Newman would come to study in 1949. Moholy-Nagy saw no fundamental distinction among any of the medium’s uses. For him, the technology opened up new ways of perceiving and representing reality, and the point was to apply that new vision in every situation. This is precisely the gospel that Newman would follow throughout his career, starting under the tutelage of the institute’s two most accomplished faculty members, Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. As Newman put it, “They taught you to keep your mind open and go further, and always respond to what you are making.”

That single idea of pushing boundaries threads through Newman’s career; therefore, his early projects in Chicago, especially his graduate thesis, demand a closer look. They predict the kind of approach he would take to all of the photographs he has since made. Its Bauhaus-inflected title was: “A Creative Analysis of the Series Form in Still Photography,” and it united Newman’s interest in social photography with an impulse to explore the medium. Exhibited, praised, but never published, these terse black-and-white series now look prescient. Angled shadows of pedestrians cut by the grid of sidewalk concrete, shop window displays, manhole covers in close-up, people sleeping on park benches — the photographic groups straddle a line between inventory and musical composition, and between social document and formal experiment. At the same time, Newman also worked for Hull House, a pioneering social welfare organization. He photographed on the street and made portraits of African Americans that, within the confines of social documentary, display an unusual range of approaches. Newman was never one to break visual rules for the sake of breaking them, as Robert Frank did, but Newman’s street photographs often anticipate Frank’s incisiveness about race in America.

During his early years in Chicago, Newman also met Yasuhiro Ishimoto, a fellow student, and together they made the documentary film The Church on Maxwell Street, about a revival meeting in Chicago. The influence of film on the early series projects is exciting. Rhythmically they read almost as filmstrips. The graduate faculty committee of the Illinois Institute of Technology, which had absorbed the Institute of Design, did not see it quite that way and wasn’t inclined to award him a degree. As Newman tells it, Harry Callahan was unsure if he could present the thesis. “Aaron Siskind went to Callahan and said, ‘Harry, these people will always be trouble. Fight for the kid.’” He did, successfully.

The other defining experience of Newman’s years in Chicago was color film. The model language for all art photography at the time was black and white. But Arthur Siegel, a formal pioneer whose contributions to photography are not yet fully acknowledged, was shooting with color film at the institute. For Newman, color was a revelation that made perfect sense. “We see in color, so black and white is technically a handicap for representing the world.” Color photographs would not begin to be accepted in the world of art photography for 20 years, but it was already becoming the lingua franca of picture magazines such as Life, Look, and a few years later the fledgling Sports Illustrated. Newman’s images would be associated with all three. Even before he graduated, he began a career of innovation in color photography, starting with Kodachrome, that would cross the boundaries between commercial and art practice.

Now that Newman’s work is being gathered and presented in this survey, these accomplishments stand out like islands in a broad stream. First and most importantly, he took color photography where it was not used to going: into the street. In the heyday of American street photography, from roughly 1940 to 1965, Americans had become used to a noir world of urban encounters, with sharply etched portraits, quirky scenes, and a dramatic play of light and shadow. By the time Newman left the institute he had already mastered the idiom. But when he applied color, he transformed it. Newman never needed to “translate” from the graphic forms of black and white to the complex temperatures and emotional undercurrents of color. He grasped the need for new compositional strategies. His color is active, even chaotic, challenging the eye as reality does. When he shot his first photographs in Times Square and Broadway in the 1950s, Newman treated the billboards and marquees as the visual carnival they were. He used a backpack strobe to light people on the street and tungsten film for the various light sources. The result has the effect of literally raising a visual curtain on Broadway and on Times Square. What the images lose in mood and graphic contrast they gain in activity and theatricality. In these photographs, lurid and dazzling, a new kind of beauty is born.

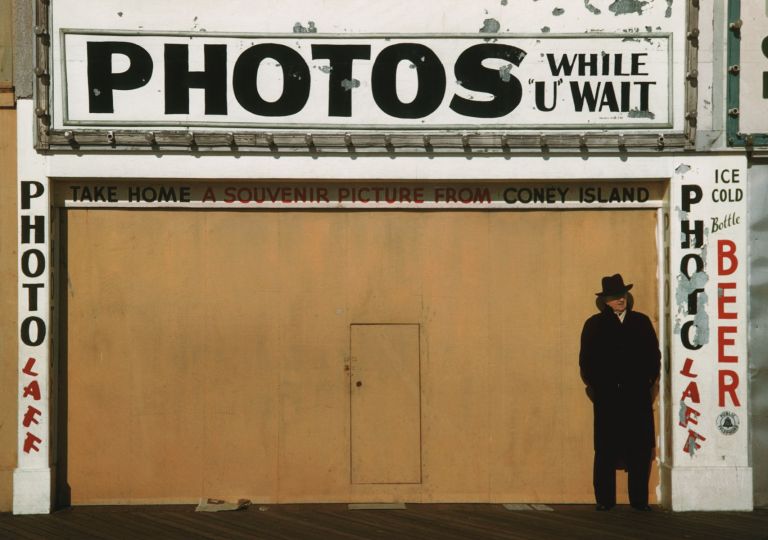

During the same period as his more hectic street work, he visited Coney Island in the winter. Shooting with a 35-millimeter camera, he managed to impart to his images of people on the semi-deserted streets the stateliness of large-format photography. To some degree, the sharp-etched shadows and zones of color resemble Harry Callahan’s work, and the architectural quality of still observation is akin to Walker Evans’s. But Newman could not be content with the austerity of their formalism. Form, yes, but human content was just as important. As he later remarked, “I was thinking of Walker Evans, but I wanted life in my photographs, people— and the written word, signage, just like the Farm Security Administration of the 1930s.”

With the renewed interest in street photography among a young generation, the rediscovery of Marvin Newman’s work has already begun. His formal intelligence in the service of human sympathy, his acute sense of life’s irony and beauty, provide touchstones for photographers. And not just for them, but for everyone seeking to understand, amidst the rising tide of images in the digital age, what photography can communicate about the lives we lead and the world around us.

Lyle Rexer

Lyle Rexer is a New York–based writer, curator, and art critic. This is an introduction of the book Marvin E. Newman published by Taschen in 2017.

Marvin E. Newman, le goût de la modernité

March 9 to June 2, 2018

Galerie Les Douches

5 Rue Legouvé

75010 Paris

France