Received during the weekend from Robert Pujade.

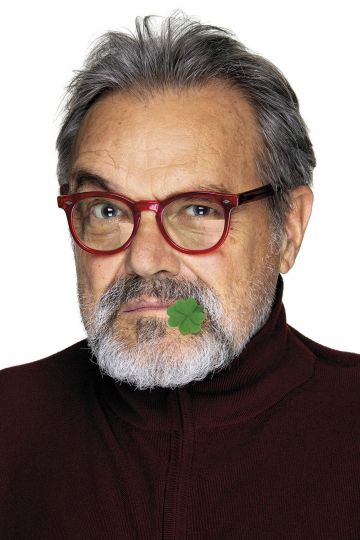

I allow myself to send you some documents relating to the work of Jean-Baptiste Carhaix who died on March 7th in Lyon.

His photographic work, haunted by death and criticism of religiosity is, as you know, considerable. In the early 80s, he produced a unique report on the “Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence” in San Francisco, of which he depicted the courageous but radiant, sinister but joyful epic. This report was followed by a heroic staging of the founding “Sisters”, almost all of whom are now dead from AIDS. In 1994, Lucien Clergue allowed me to exhibit his sometimes scandalous images during the Rencontres de la Photographie. Last year, Le Mucem paid him a brilliant tribute in the exhibition devoted to the AIDS years.

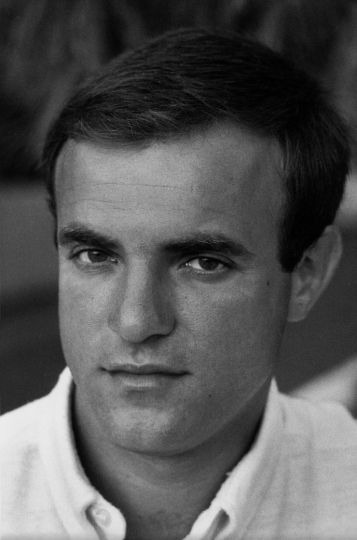

Jean-Baptiste was one of my great friends. I met him more than thirty years ago on his return from the United States and in recent years, knowing that we were doomed, we have worked together for a monograph which I will publish soon.

Robert Pujade

The Conjuration of Idols.

(About the photographic work of J.B. Carhaix)

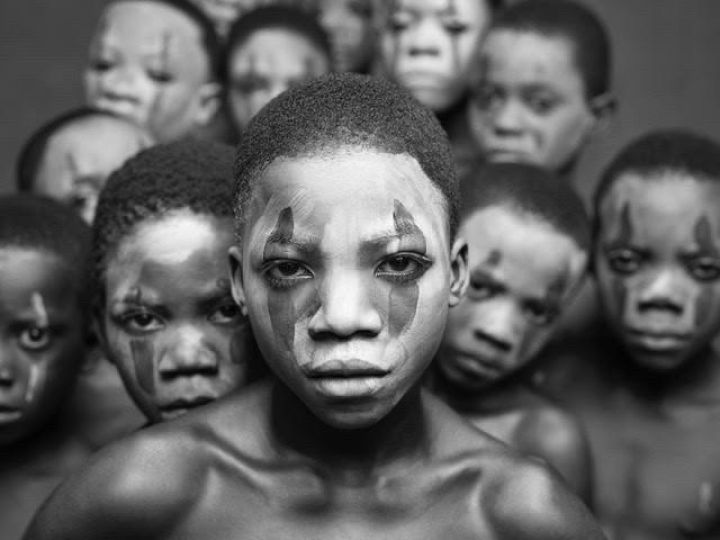

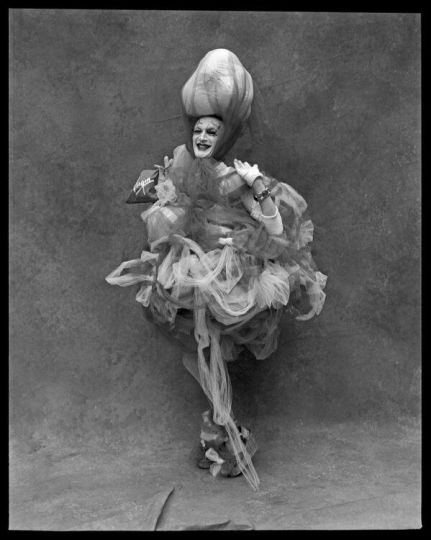

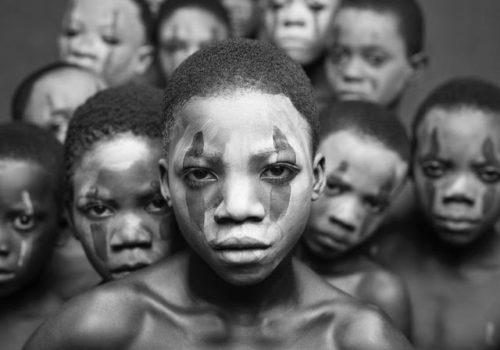

The project carried out by Jean-Baptiste Carhaix with the “Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”, between 1983 and 1993, resounds in the world of photography like a “Chant Nouveau”. He develops with grandiose emphasis a fresco on human destiny which is fulfilled on the borders of reportage and legend.

The “good sisters” of San Francisco and their heroic destiny constituted the framework of a painful epic linked to the history of the AIDS years, and the photographs evoke the exuberant aspects of this choir of transvestites in individual or group portraits. which manifest both their singular appearance in public and their gradual disappearance from the scene of existence.

But the work of the photographer could not be limited to this single report of the event which was, moreover, the subject of assiduous reporting between 1979 and 1983.

Jean-Baptiste Carhaix composed, from these characters who are already images in themselves, a baroque staging where enjoyment and death are summoned with a view to a meticulous photographic exploration. This exploration unfolds through a series of “pious images”, as their author calls them. Indeed, in these images, the figures made by the transvestites correspond more to movements of enthusiasm than to their natural attitude and they express faithful and ritualized attention to essential human concerns.

The ten years of research with the “Sisters” decline an oratorio in three acts which reveals the stages of a mystical journey during which photography is located in close proximity to the unrepresentable of sensation and death.

The first act is set in San Francisco. In the fullness of their difference, the nuns evolve on the heights overlooking the bay, or in streets marked with distressing graffiti: in a beautiful black and clear disorder, the photograph demonstrates the essence of ecstasy.

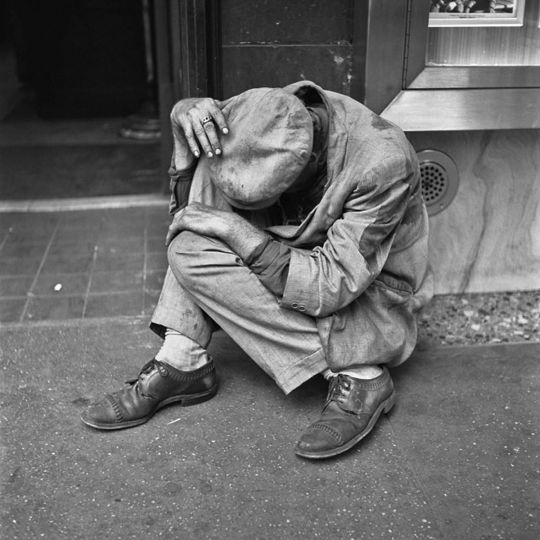

In the second act, Jean-Baptiste Carhaix engages in an essay on death: the series of dances of death and trophies that he composed in the studio, – at a time when many of his models were decimated by the epidemic still life studies strive to explore the depths of human anguish and attempt to progress further down the obscure path traced by the mortuary symbols of darkness and bones.

The third act discovers the rebirth of the choir of nuns: a “third day” casts its light on the renewed group, more majestic and higher than ever on the heights of the city of San Francisco.

In each of these moments, the staging of the characters, like the composition of the still lifes, impose their stylized presence which obeys a musical spirit. The photograph seems in direct contact with the lyrical drama.

All these images conspire to exclude themselves from any recognized genre: we are no longer in the report and yet, the true story of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence makes the game to which they lend themselves even more pathetic. In the triptych where she “rehearses” her death in ecstasy, Sister Marquise de Sade drags in her convulsive fall the extinction of the light on the city she dominates.

We are not in the portrait either, since we do not have access to the faces, but to the luxuriance of make-up, to the mask of the idols.

The photographic approach of Jean-Baptiste Carhaix is a spiritual journey that cultivates the level of the idol, understood as an image carrying a divine distinction. Dionysian excess and madness preside over the staging. On a horizon that ends in the open sea, Sister Dana Van Equity, drunk with joy, raises in a crucifixion the large veil of mourning drawn by her dress tossed by the winds.

In this sense, the good sisters of San Francisco are not a scoop, but available appearances from which the author drives his tragic vision. The snapshot is no longer the reporter of an event. It summons, through formulas of images, the essence of a feeling targeted by the project manager, by theatricalizing the posture of the models to give them the appearance of spiritual exercises.

In this scenography where person-images lend their light to the body of the image, a conjuration of idols is accomplished with a view to an autonomous expressiveness.

To achieve this singular expression, the photograph that does not say a word moves here towards a language of the body. As Jacob’s injury to the hip is the only visible mark of his encounter with the Angel, the ecstasy, the intense contemplation, the shocked contortions provide music of meaning with the range of its own language. The photographic as such delivers its own intelligence of human destiny.

In turn, each of the nuns freezes into a martyred figure that immobilizes the ecstatic transport. Their superb and obscene getup, their precise and overabundant make-up, in contrasting opposition to the angles of the city, testify to a profound truth of the freedom of pleasure, in the neighborhood of a god, and against a backdrop of bacchanalian ruckus.

Jouissance, as it is played out here against a backdrop of surprising death, shines through from these photogenic contiguities between the liveliness of pleasure drawn on a body and the social reserve delimited by the landscape.

By metaphor, one could say that Jean-Baptiste Carhaix proposes a metaphysics of enjoyment and death; it would only be a way of indicating how far his gaze goes. The use he makes of the sole resources of photography deploys a form of knowledge approaching the essential, like “hyperphysics” which would remain the exclusive domain of manifestation through the image.

It would be necessary to recast this pretty name of hyperphysics, to extract it from the Kantian terminology, because it exhausts in it all human claim to know, and, in this particular claim, to make it signify: physical presence of a gaze attentive to the supersensible. It would then be fully suited to this level of the image, cultivated for itself in the sense of a progressive ascent of sensitive vision towards the essences of pleasure, pain and death.

Robert Pujade