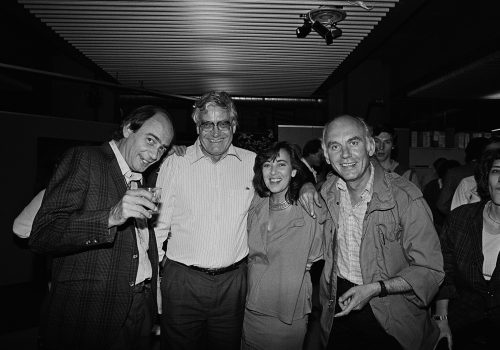

Interview with Hubert Henrotte, founder of the Gamma and Sygma agencies, published in the book “40 years of photojournalism – Generation Sygma” Interview with Jean Louis Gazinière.

In May 1973, your divorce with Gamma, which you founded, was consummated. How are the first steps of Sygma, your new agency going?

HH: To be honest, after six years of hard work for Gamma, I especially want to take a step back. But the photographers, led by Henri Bureau, finally convince me. The agency was officially created on May 14. I continued to fight to ensure that the golden rules I imposed on Gamma applied to Sygma: crediting photographers and the agency, monthly statements, advance fees and films. It was not easy. Unlike Gamma where we started at five, this time we are about thirty and penniless! The newspapers and the editorial staff trust us: Roger Thérond at L’Express, for example, assures me that he will continue to work with me and gives me a minimum monthly guarantee. At that time, there were great professionals in the newspapers who had an instinct for photojournalism, an eye, a culture. We now have three major French photo agencies: us, Gamma, which remains world famous, and Sipa, now well established in the landscape.

What is the field of competition between these three agencies?

HH: That of the scoop! Newspapers buy exclusivity. Being first is a top priority. So sometimes we send two photographers at the same time when there is a big news story: one takes pictures for an hour, jumps on a plane to bring them back to Paris in order to distribute them the next day. The other covers the event for a few more days. All means are good. Some film packages have even mysteriously disappeared, victims of this fierce competition between agencies.

When it comes to people photography, Sygma is quickly taking a step ahead of its competitors. How do you explain it?

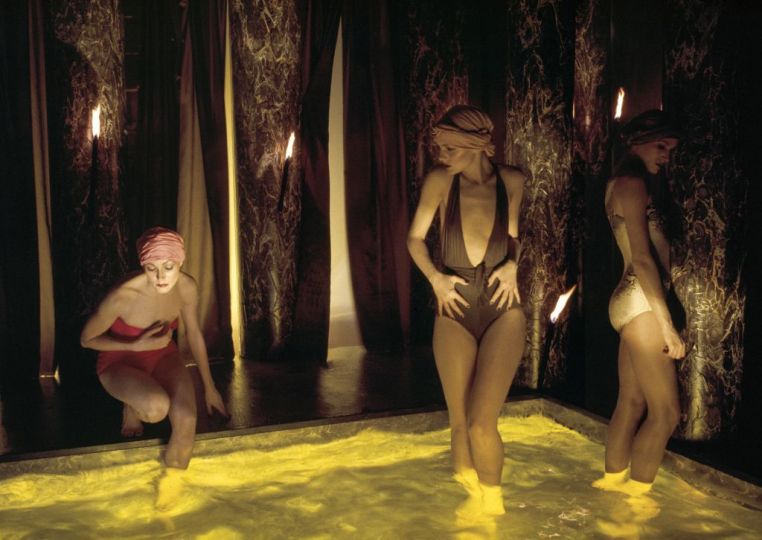

HH: It is a specificity of the agency and the reserved area of Monique Kouznetzoff. From the start, we decided to create a “people” department and another “news” department. A third dedicated to the magazine will be created a little later. Very quickly, Sygma had to rely on the ” people” to ensure its financial balance. Monique decided to open an office in the celebrity capital of the world, Los Angeles. She chose photographers whose work is dedicated to celebrities, big names like Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Dominique Issermann, Bettina Rheims or Helmut Newton. She plays the matchmaker between them and the stars. We also decided to mount special operations like that of Brigitte Bardot on the ice floe, fighting for the cause of baby seals. The idea behind the idea was the actress herself. She wanted to strike a big blow and asks us to co-organize the expedition. I said yes to everything: the private jet, the living expenses and even the TV crew whose film we will be producing. And I put a condition: to have the exclusivity of the images. Bet won. The photos went around the world.

And the news in all this?

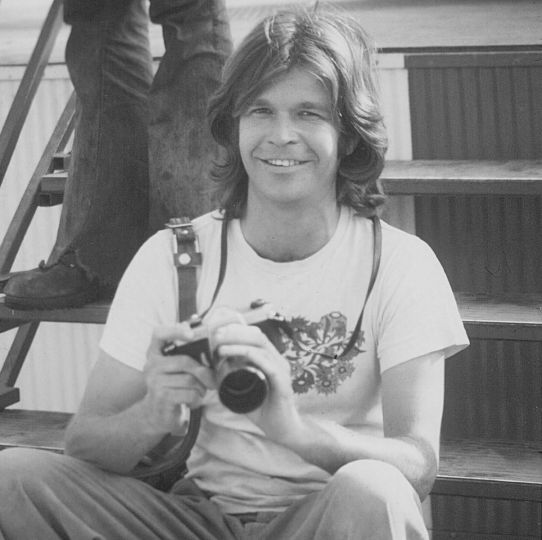

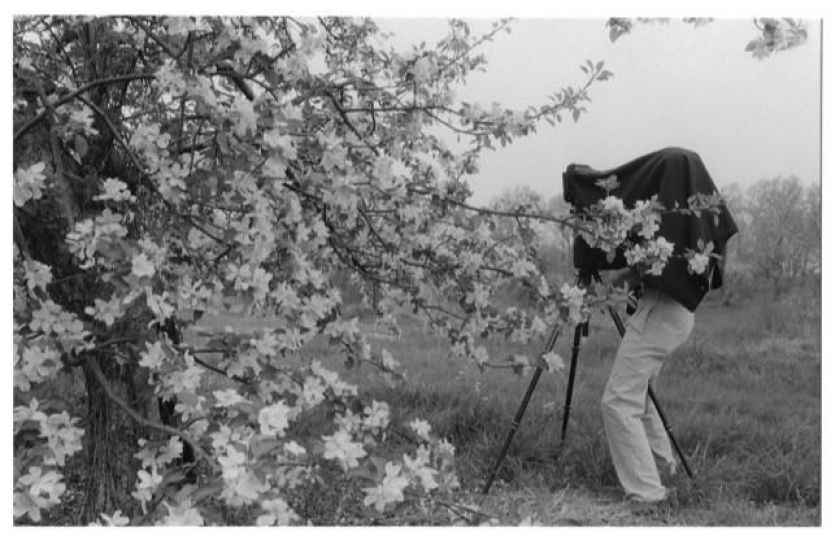

HH: People make huge sums of money – almost half of Sygma’s turnover – but news is the agency’s first identity card, the historic showcase of photojournalism. Unlike today, photo agencies then have the hand: they create, make the event. At Sygma, we focus on major prestige issues. Like this incredible long-term reportage on the scandal of children at work by Jean-Pierre Laffont. We’re also pulled a nice scoop on Red China billionaires. We find guarantees for these topics: fees were paid and sometimes there was an advance on copyright. A photographer and an editor can investigate in the field for several months.

How did the Sygma machine work?

HH: Like an editorial department. Each of the departments – people, news and magazine – is headed by an editor. their role is essential. He must not only find the right information, have flair, but also serve as a conduit between the photographers in the field and the agency. You have to reassure them sometimes, convince them to do this or that subject, often. Some only get started on the strong news, those that pay off immediately and dodge the rest. The agency operates from 5 am to 10 pm, seven days a week. So we are setting up weekend hotlines. Competition between photographers is fierce. We also have five top editors and editors for texts and captions. Added to this is an English translation service and of course a sales service, always on the alert.

How is the geographical position of Paris an asset for the development of the agency?

HH: At the time, Paris was the capital of photojournalism because it was geographically at the center of the world. Take the case of the Vietnam War: events take place at one end of the planet while American magazines, hungry for photos, are at the other end. We were in the middle, at the crossroads of communication routes. Not to mention the time difference that works in our favor: the photos sent the day before from Paris, by freight, arrive the next morning in New York for the opening of newspapers. And then, we developed a real network of offices – in New York, Los Angeles or London – but also of correspondents abroad: photographers and salespeople. Today, it is irrelevant with the Internet.

How is the agency adapting to technological challenges?

HH: We have always tried to be on the cutting edge. At the end of the 1970s, we created Sygma TV, the audiovisual production department. Monique Kouznetzoff produced a celebrity show for Antenne 2, a genre never before seen at the time. Then a daily show from 1983, for Canal +. But the adventure faded in the 1990s. We are also pioneers on the digital front. During the first Gulf War, the photos are still film but we used digital transmission, by satellite. It’s a revolution for an agency like ours. But we cannot keep pace with the technological challenges: the financial investments are huge and the demand for newspapers has decreased a lot with the economic crisis. This is why I decided to take a financial partner.

How do you view photojournalism and the profession today?

HH: Everyone thinks of themselves as a photographer today. And technically, the photos are indeed good because everything is automatic. There is nothing more to fix, no more fine-tuning to do. That’s a big difference: back in the day, you had to be a journalist and an excellent technician. If technique is no longer an issue, Mr. Everybody still lacks journalistic training. A photojournalist is above all a journalist. He must know how to write in pictures. The profession therefore still exists. Working conditions, on the other hand, have deteriorated drastically. See the insane risks some young independent photographers took during the Arab Spring or the war in Syria. But we also need distribution media for these quality photos. For the moment, magazines and newspapers, strangled by the crisis, are in a logic of low prices, minimal cost. For now … I think everything has to be (re) created. For that, it would be necessary to accept to slow down the rhythm of the images – fifteen to twenty thousand images received per day in the newsrooms today! -, to have real good subjects with reportages built over time. Against today’s cult of immediacy. Is it possible ?

The agency trilogy is still available. With as co-authors Marie Cousin, Sylvie Dauviller and a whole team of young journalists from CFPJ and myself

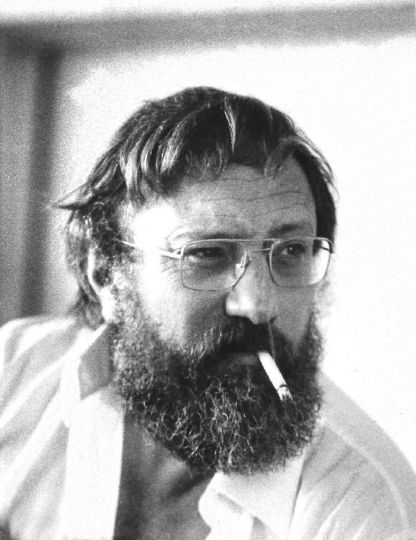

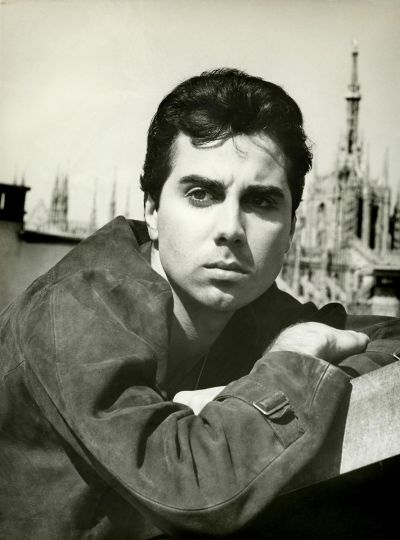

Michel Setboun