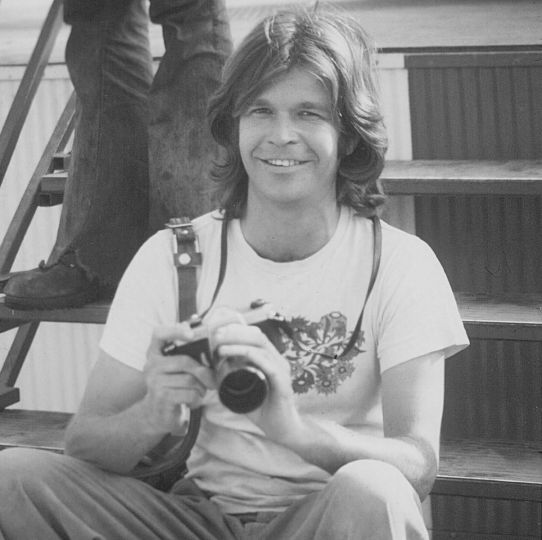

As chief of photo operations for The Associated Press in Saigon for a decade beginning in 1962, Horst Faas didn’t just cover the fighting — he also recruited and trained new talent from among foreign and Vietnamese freelancers.

The result was “Horst’s army” of young photographers, who fanned out with Faas-supplied cameras and film and stern orders to “come back with good pictures.”

He and his editors chose the best and put together a steady flow of telling photos — South Vietnam’s soldiers fighting and its civilians struggling to survive amid the maelstrom.

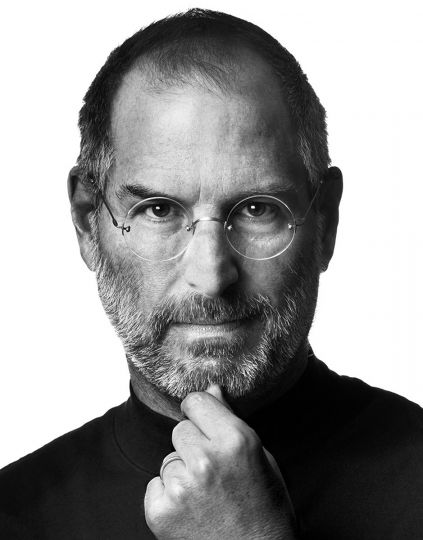

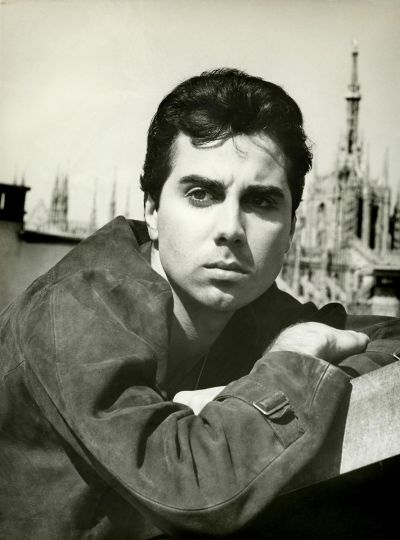

Faas, a Pulitzer Prize-winning combat photographer who carved out new standards for covering war with a camera and became one of the world’s legendary photojournalists in nearly half a century with the AP, died Thursday in Munich, said his daughter, Clare Faas. He was 79.

A native of Germany who joined the U.S.-based news cooperative there in 1956, Faas photographed wars, revolutions, the Olympic Games and events in between.

But he was best known for covering Vietnam, where he was severely wounded in 1967 and won four major photo awards including the first of his two Pulitzers.

“Horst was one of the great talents of our age, a brave photographer and a courageous editor who brought forth some of the most searing images of this century,” said AP Executive Editor Kathleen Carroll. “He was a stupendous colleague and a warm and generous friend.”

Among his top proteges was Huynh Thanh My, an actor turned photographer who in 1965 became one of four AP staffers and one of two South Vietnamese among more than 70 journalists killed in the 15-year war.

My’s younger brother, Huynh Cong “Nick” Ut, followed his brother at AP and under Faas’s tutelage won one of the news agency’s six Vietnam War Pulitzer Prizes, for his iconic 1972 picture of a badly burned Vietnamese girl fleeing an aerial napalm attack.

Faas was a brilliant planner, able to score journalistic scoops by anticipating “not just what happens next but what happens after that,” as one colleague put it.

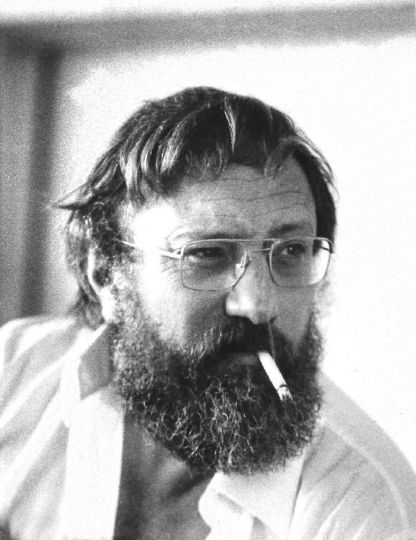

His reputation as a demanding taskmaster and perfectionist belied a humanistic streak he was loath to admit, while helping less fortunate ex-colleagues and other causes. He was widely read on Asian history and culture, and assembled an impressive collection of Chinese Ming porcelain, bronzes and other treasures.

“Horst Faas was a giant in the world of photojournalism whose extraordinary commitment to telling difficult stories was unique and remarkable,” said Santiago Lyon, AP vice president and director of photography.

“He was an exceptional talent both behind the camera and editing the work of others and even in the grimmest circumstances he always made sure to live life to the fullest,” Lyon said. “He will be sorely missed by scores of colleagues, especially that reduced group with whom he covered conflict, particularly the Vietnam generation.”

In later years Faas turned his training skills into a series of international photojournalism symposiums.

Faas also helped to organize reunions of the wartime Saigon press corps, and was attending a combination of those events when he became ill in Hanoi on May 4, 2005.

He was hospitalized first in Bangkok and then in Germany, where doctors traced his permanent paralysis from the waist down to a spinal hemorrhage caused by blood-thinning heart medication.

Although requiring a wheelchair, he continued to travel to photo exhibits and other professional events, mainly in Europe, and collaborated in the publishing of two books in French — about his own career and that of Henri Huet, a former AP colleague in Vietnam. Faas also made two arduous trips to the United States, in 2006 and 2007.

His health deteriorated in late 2008. Hospitalized in February for treatment of skin problems, he also underwent gastric surgery.

Faas’ Vietnam coverage earned him the Overseas Press Club’s Robert Capa Award and his first Pulitzer in 1965. Receiving the honors in New York, he said his mission was to “record the suffering, the emotions and the sacrifices of both Americans and Vietnamese in … this little bloodstained country so far away.”

Burly but agile, Faas spent much time in the field and on Dec. 6, 1967, was wounded in the legs by a rocket-propelled grenade at Bu Dop, in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. He might have bled to death had not a young U.S. Army medic managed to stem the flow. Meeting Faas two decades later, the medic recalled the encounter, saying, “You were so gray I thought you were a goner.”

On crutches and confined to the bureau, Faas was unable to cover the February 1968 Tet Offensive, but directed AP photo operations like a general deploying troops against the enemy. AP photographer Eddie Adams came back with the war’s most famous picture, of Vietnam’s national police chief executing a captured Viet Cong suspect on a Saigon street.

“Generally we had to go pretty far into the field but this was a situation in which the war came to us. It was right next door,” Faas recalled.

He often teamed with Pulitzer Prize-winning AP reporter Peter Arnett to produce powerful and exclusive reports such as the 1969 story of Co. A, an Army unit that balked at orders to move against the enemy. Faas witnessed the “combat refusal” incident during an effort to reach the site of a helicopter crash that had killed seven U.S. soldiers and AP staff photographer Oliver E. Noonan.

Born in Berlin on April 28, 1933, Faas grew up during World War II and like all young German males was required to join the Hitler Youth organization. Years later, he wrote that Allied air raids and “the fascinating spectacle of anti-aircraft action in the sky” were part of daily life, as was being required “to stand at attention in school and listen to an announcement that the father or older brother of a classmate had died for fuehrer and Fatherland.”

As the war ended in 1945, the family fled north to avoid the Russian advance on Berlin and two years later escaped to Munich in West Germany.

During the postwar Allied occupation, Horst became the 15-year-old drummer for a black GI jazz band in Munich. Asked recently where he learned the drums, he said, “I didn’t know how. I just played them.”

In 1960, at age 27 and an AP photographer for four years, Faas began his front-line reporting career in the Congo, then Algeria. In 1962 he was reassigned to the growing war in Vietnam where he landed on the same day as Arnett.

Faas for a time shared a Saigon villa with the late New York Times correspondent David Halberstam, who said of Faas, “I don’t think anyone stayed longer, took more risks or showed greater devotion to his work and his colleagues. I think of him as nothing less than a genius.”

Faas left Saigon in 1970 to become AP’s roving photographer for Asia, based in Singapore, ranging widely on assignments. He teamed with New Zealander Arnett on a cross-country reporting tour of the United States as seen by foreigners, and covered the 1972 Munich Olympics where he photographed a ski-masked Palestinian terrorist on the balcony of the building where Israeli athletes were being held hostage, hours before they were murdered at the airport.

The same year, he won a second Pulitzer Prize, along with Michel Laurent, for gripping pictures of torture and executions in Bangladesh. Laurent later became the last journalist killed in the Vietnam War, two days before the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, while working for the French Gamma photo agency.

In 1976, Faas relocated to London as AP’s senior photo editor for Europe, until he retired from the news agency in 2004.

He was co-editor of “Requiem,” a 1997 book about photographers killed on both sides of the Vietnam War, and was co-author of “Lost Over Laos,” a 2003 book about four photographers shot down in Laos in 1971 and the search for the crash site 27 years later.

Survivors include his wife, Ursula, and his daughter.

Richard Pyle covered the Vietnam War for five years and was AP Saigon bureau chief 1970-73.

Copyright © 2012 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.