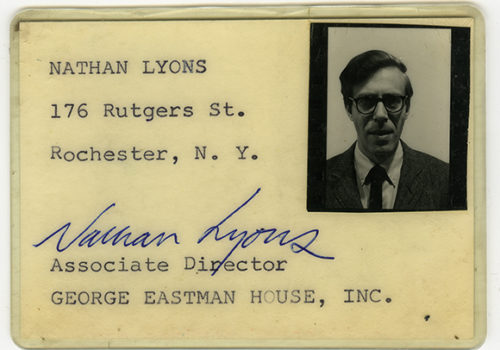

A generation of photography pillars is frittering away. On Wednesday August 31st 2016, Nathan Lyons (1930-2016), co-founder of the Society for Photographic education (1962 and 1963), assistant director at the George Eastman House (until 1969), and mostly known as the founder and director of Visual Studies Workshop and its international magazine, Afterimage, (1969-2001) passed away in Rochester NY.

Rather than a straight-forward biography which can be read on Wikipedia or the New York Times website, I would like to evoke the memory of a man who changed the course of my life, as he did for so many. I met Nathan Lyons for the first time in 1988 in Arles (France) where he was teaching a 5-days’ workshop–to which I had registered–at the local photo festival, Les Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie (first created in 1970). The topic of the workshop was, broadly speaking, visual literacy, and more specifically how to read photographs and organize them in meaningful sequences and series, one of Nathan’s favorite subjects. As, then, a certified professor of English, a free-lance photo-journalist for a regional newspaper, and a secretary of a regional committee for photography, the topic and Nathan’s short biography must have convinced me to register and spend five days of my summer vacations studying with him. The workshop was taught in English.

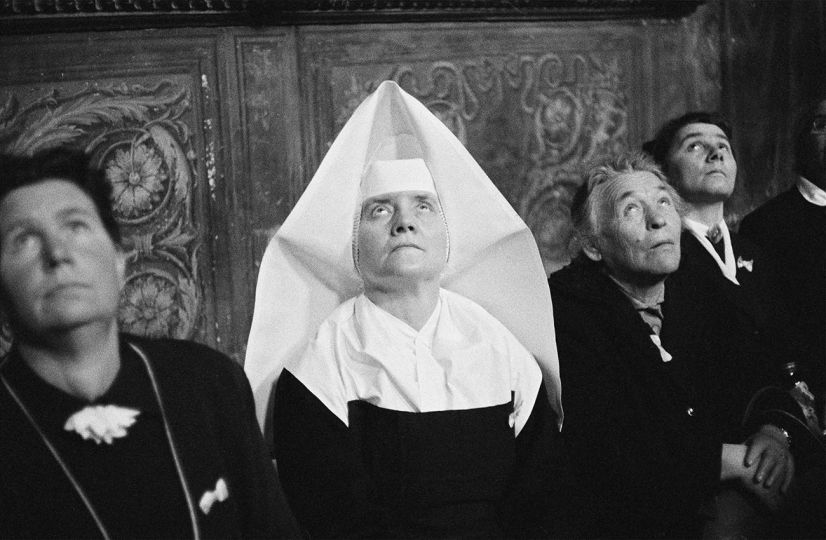

Nathan did not speak any French, Stuart Alexander his remarkable assistant did, a little, so a young English student, having just spent a year in France, had been appointed by the festival to help with the translations. The problem was that we also spoke “photography,” she did not. Soon I found myself assisting the assistant, which allowed me to have a few conversations with Nathan, especially during his regular cigarette breaks. One day was entirely dedicated to the study, analysis, and to a following discussion on Robert Frank’s The Americans. That day was a revelation to me. Nathan quietly explained how the themes in the book were interwoven, how the structure of the book, the relationships it established between groups of photographs duly “flagged” by photographs including the American flag, created meaning beyond the sum of the meaning of each photograph.

The Americans was in fact an amazing analysis not just of American culture in the 1950s, of its “social landscape,” but also of the medium at that point of its history. It also proposed a different, if not radical, solution to the structuring of photographic books, going far beyond a simple if not simplistic accumulation of photographs, or a linear narrative structure. Reaching beyond the accumulation of images to create a system that explored the work further than its obvious content, clarifying the author’s “voice,” collaborating with the photographer to adapt the work to the space (book, exhibition, slide show,…) in which it was displayed was in fact the real goal of a curator, a publisher, or a gallery-owner. It was the role and more, the duty, of a teacher to bring his/her photo-students to this level of understanding and practice of the medium.

It would take me another similar workshop the following year with Régis Durand (at the time photo-critic for Art Press, soon to become the director of the Centre National de la Photographie in Paris), and two or three years of analyzing and processing the situation of photo-education and visual literacy in France. At the time, the lack of exposure to and study of photography as a cultural phenomenon of our times and as a full-fledged means of expression in the French educational system, from middle school to college, frustrated me. I felt that if the educational institutions did not embrace photography, I had to bring photography to them. I had already been doing that at K-12 level and in various photo-clubs. I decided to go back to college and register in a Ph. D. program, in an English department where my research would be on English and American photography. Once my course-work done, my plan was to write my pre-dissertation (DEA memoir) on Bill Brandt and my dissertation on contemporary American photography–the latter for personal reasons too as my own practice had shifted from traditional French street/humanistic photography to landscape used as a metaphor.

My next step was to contact Nathan Lyons and ask him for advice regarding where I should do my research. His answer was that New York City sounded like an obvious answer, but there access was not always facilitated, and the cost of life was superior to what it was in Rochester. Between the George Eastman House library and archive, the Rochester Institute of Technology, the University of Rochester, and of course Visual Studies Workshop, I had probably more than I could research and use. I could not then imagine how right he was and how his advice would radically change my life. The George Eastman House and even more, Nathan’s Visual Studies Workshop became my favorite research centers, not just because of their physical resources, but, above all, because of their human ones. Between conversations with Nathan himself and Bill Johnson, then in charge of VSW’s research center,Bill is a bottomless well regarding the history of photography, including its anecdotes–numerous meetings and interviews of photographers in Upstate New York (which I jokingly came to nickname the Bermuda triangle of photography with its unbelievable wealth of photographic knowledge spreading between Syracuse (Lightwork), Rochester (GEH, RIT, U of R, VSW), and Buffalo (CEPA, SUNY Buffalo, “Buff. State”, Albright-Knox Gallery)) I realized and identified the limits of my photographic experience and was given the tools to expand my expertise until the day in December 2002 when I became both a member of the teaching staff at VSW and the editor of Afterimage.

I had then learnt that Nathan Lyons had come to Rochester by chance after spending three years of the Korean war as an intelligence photographer. After graduating from Alfred University in 1957 with a BA in English literature–thence I suppose his fascination for both photographs and words–Nathan was on his way from Alfred to Chicago. As he was visiting Rochester, he stopped and met Minor White at the George Eastman House. The museum had just opened its doors in 1949. Beaumont Newhall, its first curator of photographs had recruited Minor White on the recommendation of his friend Ansel Adams. White was in charge of the museum’s publication, Afterimage. He asked Nathan if he would be interested in becoming his assistant. Nathan agreed.

Three years later he would be appointed assistant director and would, with like-minded people around him, accomplish an unmatched work for photography: developing teaching and training programs, resources for teachers (books, catalogues, compilations of historical texts on photography, sets of slides for schools and universities), co-founding the Society for Photographic Education (1962-63), promoting the medium through a program of traveling exhibitions, promoting young photographers. Six years after his hiring he would have not only exhibited Lee Friedlander for the first time but Bruce Davidson, Carl Chiarenza, Ken Josephson, Eugene Meatyard, Ray Metzker, Duane Michals, Pete Turner, Jerry Uelsmann, Garry Winogrand, Paul Caponigro, Jerome Liebling, Art Kane, William Klein, Art Sinsabaugh not to mention Boubat, Brassaï, Burri, Clergue, Gardin, Gautrand, Giacomelli, Harbutt, Hosoe, Mayne, McCullin, Riboud… It can probably be said that when he resigned from the GEH in 1969, in solidarity with a co-employee fired for alleged “sorcery,” his role and impact regarding American photography eclipsed John Szarkowski’s at the Museum of Modern Art (New York).

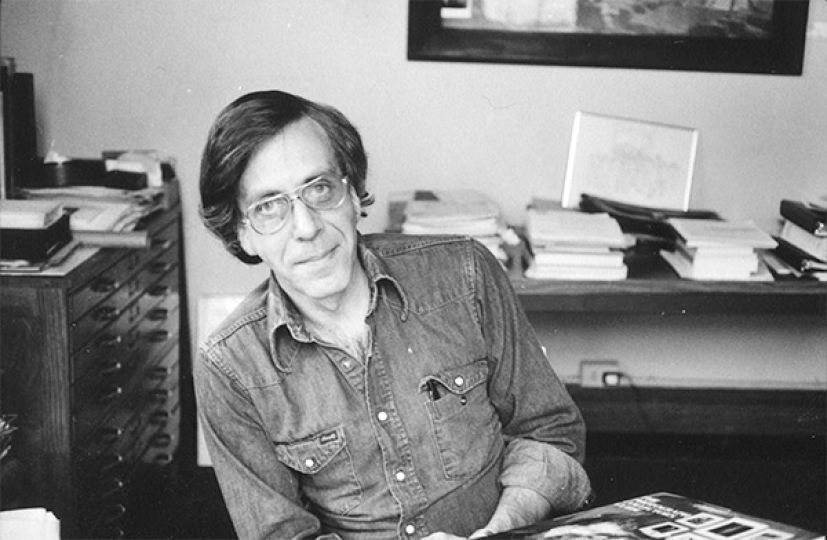

Following his unexpected departure from the GEH, Nathan Lyons decided to create his own (alternative) institution, a block away from the museum, in a carpenter’s workshop on Elton Street. With his convincing the State University of New York at Buffalo to let him create a Master’s of Fine Art program for them in Rochester, Visual Studies Workshop was born… in an empty shell, in 1969. From its very inception a tradition was established at VSW that the teaching staff and the students were responsible for the creation and maintenance of the place. Everyone had to be involved in the communal teaching/learning experiment. Over forty years later, in 2001, as Nathan was going to retire, I happened to find him one morning still sweeping away the autumn leaves that the northwest wind usually blew into the lobby every time someone walked into 10 Prince Street (the second and current location of VSW). From the end of 2002 to the beginning of 2005, while a member of the VSW faculty and an editor of its magazine Afterimage (founded in 1972), I, in turn, would sweep away the leaves, maintain my office, participate in the general cleanings or paintings.

After chairing the Society for Photographic Education, Nathan would be asked to sit at many a committee throughout the country, National Endowment for the Arts included. Nathan’s former students can be found on the rosters of most prestigious American institutions in the arts (MoMA, Metropolitan Museum, International Center of Photography, George Eastman House,…), teaching in universities throughout the country, the recipients of NEA grants and Guggenheim Fellowships, leading amazing projects such as Mark Klett and the three Rephotographic Surveys, or Anne Tucker, one of Nathan’s very first students who recently (June 2015) retired from the Houston Museum of Fine Arts while one of the finest American if not world curators, building an incredible collection of photographs (including the whole set of The Americans), creating seminal (often traveling) exhibitions (Richard Misrach, Women in Photography, the History of Japanese Photography, Brassaï, Ray Metzker, Robert Frank, the Photo League,…).

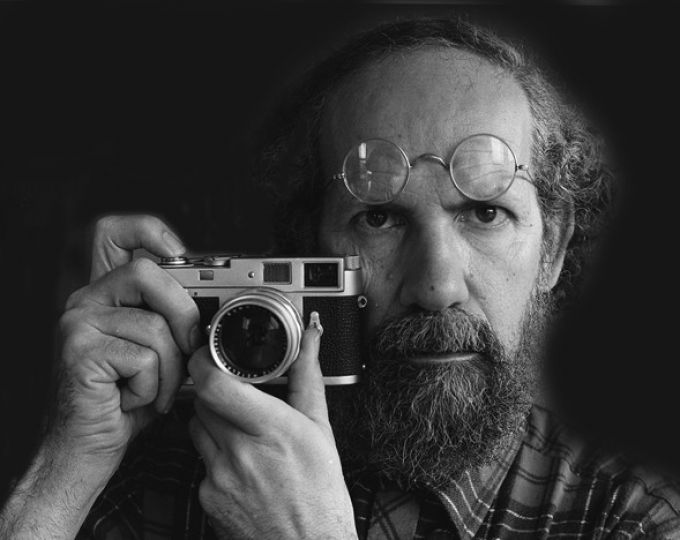

Until his last breath, Nathan remained attached to and active not just in the local photographic scene but across the country and the world, writing, lecturing, exhibiting, always opening his door to anyone eager to speak about photography. After exhibiting over some sixty years–including inclusions in John Szarkowski’s famous shows, The Photographer’s Eye and Mirrors and Windows–and a well-deserved retrospective at the George Eastman House in 2000, and after his retiring from VSW at the age of 71, Nathan went back to work,on his own personal photographic work, producing and exhibiting new projects, publishing new books and portfolios. His first book, a classic now, Notations in Passing, came out back in 1974. Since then, he has published Riding First Class on the Titanic (1999), After 9/11 (2003), and Return Your Mind to Its Upright Position (2014). Although famous for his black and white photographs, he was working on a series of digital color images.

Nathan Lyons brought a feast to the photographic table; he dedicated his whole life to the medium. Even those of us in photography who never met him, never even suspected his existence and work for the field, owe him far more than they know; in fact, they have been using his legacy without even knowing it. He is a great man in the history of photography, one who left us discreetly, without fuss, as he had always lived, surrounded by his family and dear friends… photographers.

Bruno Chalifour, Rochester, Sept. 5, 2016.