This is the farewell exhibition of François Cheval at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce: Henri Dauman and Stephen Shames. Until his show in Paris two years ago at Palais d’Iéna, Henri Dauman had remained unrecognized. However his work on the United States is impressive. Today’s edition is dedicated to him.

The life of Henri Dauman deserves to go down in history. Or in the movies. Since his dream was to become a filmmaker… Although not a household name, this “war orphan” lived through the major conflicts of the twentieth century and the heydays of photojournalism. Aged 84, he is still making news with a forthcoming documentary film retracing his adventurous life and with an ambitious retrospective, The Manhattan Darkroom. Focusing on his career in the United States, the exhibition at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce covers sixty years of the archives of this Stakhanovite of photography.

We met in late January at a café in the Upper East Side, his home neighborhood in New York. Smiling and well dressed, Henri Dauman cut a handsome figure. “My apartment is a mess,” he apologized. The next day he was leaving for France where the Musée Nicéphore Niépce is hosting the ambitious traveling retrospective launched in 2014 at the Palais d’Iéna in Paris, which welcomed over 12,000 visitors. Henri Dauman is very busy but he has made himself available. Gazing with keen, unflinching eyes, sparkling with playful candor, this great neglected photographer seems to be amused by the sudden attention he is receiving.

In addition to the exhibition, he is assisting in the making of a biographical feature film in Paris, slated for release in 2018. Entitled Looking Up, the film is produced by the American Peter Jones and directed by his partner and Henri Dauman’s granddaughter, Nicole Suerez. For the purposes of the film as well as the exhibition, they needed to turn back the clock and revisit the past. They spent hours digging up the dead and rekindling memories in order to tell his story…

A painful past

Henri Dauman was born in 1933 in Montmartre. He was only nine when the yellow star badge was made compulsory in Vichy. One day in 1942, there came a pounding at the door. The French police was trying to get into the Parisian apartment he shared with his mother. Double-locked since his father’s arrest, the door held for better or worse. Terrified, Henri and his mother heard some neighbor lending his axe to the police to help break it down. As luck would have it, it was lunchtime. The police decided to come back later. In France, even in wartime, the lunch break is sacred…

Henri and his mother took the opportunity to slip away, narrowly escaping the Vel’d’Hiv roundup. Henri’s father, a French citizen of Jewish origin, born in Warsaw, was less fortunate. Interned in Pithiviers, he was later deported to Auschwitz. Henri never saw him again. Hiding with different families in Limay in the department of Yvelines, then near Alençon in Normandy, the boy was reunited with his mother in Paris only after the Liberation. Their reunion was short-lived. In 1946, the mother died, one of eight victims of poisoning by un unprincipled corner druggist selling black-market baking soda. The powder turned out to be rat poison. “I think we can call it willful homicide,” declared Henri Dauman, holding back emotion.

There followed four “bleak” years in an orphanage, as the young man had become a ward of the state. He took refuge in the movies, “in particular films noir,” and began dreaming of America… But for the moment, he became an apprentice at a photo studio in Courbevoie, then assistant fashion photographer in Paris. He also did portraits of celebrities for Radio Luxembourg and Agence Bernard, which specialized in entertainment photography. He bought his first camera, a cheap medium-format twin-lens reflex, and set out to photograph Parisian street scenes.

America upside down

Was it fate? His uncle, the last surviving member of his family, who had immigrated to the United States before the war, invited Henri Dauman to come and stay with him in the Bronx. Without giving it a second thought, Henri Dauman boarded the liner Liberté, alone with his camera, and went to meet his “American uncle.” As is often the case with Henri Dauman, the end of a sentence marks the beginning of an anecdote. And so here is one… A few hours before arrival, his Rolleiflex case containing the camera and his passport had disappeared. “I thought I would never be able to set foot on the American soil,” he recalled, still bewildered by the incident. The crew and passengers turned the ship upside down. The bag reappeared mysteriously just before the ship reached the American promised land. Nothing short of a miracle.

The young photographer disembarked in Manhattan in the dead of winter. The United States was at the height of its power. Hollywood mythologies were taking over the world. But for Henri Dauman, daily life meant the assembly line. He began by packaging women’s lingerie and enrolled in English courses. Resourceful, he soon got hired as a press photographer for the journal France-Amérique. “I photographed visiting political and cultural figures and the life of the French community in New York.”

Married at 20, he became a father at 21. To set aside enough money to buy a Leica, he saved on meals. His modest menu included “potatoes and butter, sauté potatoes, or fried potatoes.” To supplement his income, the young photo reporter devoured the news. He followed world headlines, scoured society columns, and hunted for events that he could cover for a pittance.

Calling himself a “One-Man Agency,” he shot by day and developed his films at night. He transformed his kitchen into a darkroom. Negatives hung with clothes pegs over the bathtub. He produced his own prints, which he sent around to all the French newspapers —the Figaro, Paris Match, and France Dimanche—. His determination appealed to the Americans. Eight years after his arrival in New York, he published his first story in Life Magazine on the marriage of Jean Seberg and the French lawyer François Maureuil in Marshalltown, Iowa.

A cinema enthusiast, Henri Dauman takes pride in his “cinematic vision.” New York streets are his “open air film set.” In the street, he would exploit the towering architecture of the city. He came up with the idea of placing his Leica with its wide-angle 21-mm lens, purchased thanks to his potato diet, directly on the ground. The low-angle shots reinforce the verticality of skyscrapers and the impression of the viewer’s own vulnerability and vertigo. You almost feel like Jack Arnold in Grant William’s 1957 film The Incredible Shrinking Man. In 1963, the MoMA acquired Dauman’s series on American architecture, entitled Looking Up.

An experimenter, Henri Dauman enjoyed playing with “sequences,” series of snapshots, very cinematic in character, taken on the move, which seem to plunge the viewer right in the heart of a bustling scene: one of his best pictures captures Liz Taylor entranced by a 1960 boxing match between Ingemar Johansson and Floyd Patterson. Inspired by films noir, Dauman multiplied the effects of light and shadow, reflections and cross-fades.

A star reporter at Life Magazine

One of his first photographic exploits consisted in capturing the dramatic expression of Jackie Kennedy, underscored by her black mantilla, as she walked during the funeral procession behind John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s coffin. This was November 20, 1963. In Washington, DC, some million Americans had come to pay their last respects to the assassinated president. Emotions ran high as the casket, draped over with the star-spangled banner, made its way towards St. Matthew’s Cathedral. In the crowd, Henri Dauman instinctively stepped aside for a few seconds to take a picture of the woman whose grief resonated across the nation.

Five pages of his color images—which was a first for a photographer who had previously shot only black and white—were showcased in the prestigious Life Magazine. The symbolic power of the image didn’t go unnoticed to Andy Warhol who appropriated the photo and used it in his silk-screen print Sixteen Jackies. Years after Warhol’s death, Henri Dauman sued the artist’s estate, archive, and museum for misuse of his image, which was being reproduced on calendars, posters, and other related products. “One of his silk-screen prints sold for over 300,000 dollars at Sotheby’s in 1992,” he noted. Henri Dauman’s lawyers negotiated a settlement for the suit which had lasted seven years.

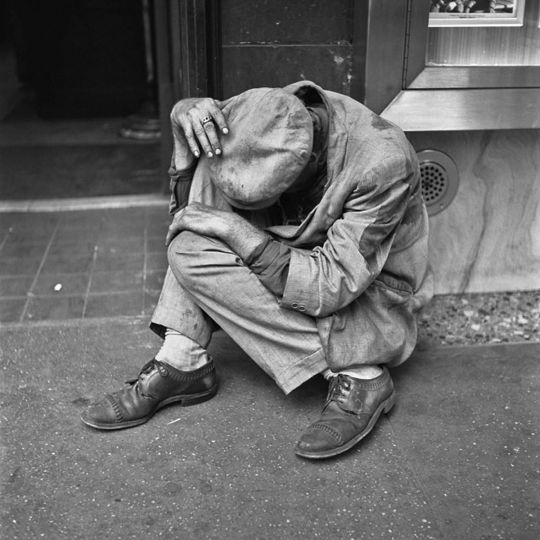

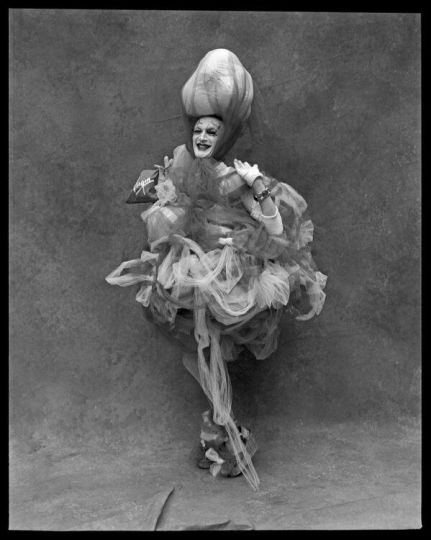

Having become one of the star reporters of Life Magazine, as well as Newsweek and the New York Times Magazine, he hunted for the scoop in the street and off-stage; he took a swipe at street gangs in the Bronx as well as at the idle petty bourgeoisie at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami, at political leaders as well as show-biz stars and the world of art. From civil rights protests in Washington to the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, to feminist movements, Henri Dauman “unwittingly” pictured the transformations of the American society as seen through the eyes of an exile. He was both at the center and on the margins of history. “I was lucky to create a series of reportages which, at the end of the day, showed the evolution of the United States. I was not aware of it at the time; I was caught up in the moment,” he explained, sometimes trying to find the right word as he switched between French and English, his adoptive language.

In the name of professional freedom, he declined the offer of a permanent post at Life. “Becoming part of a team would have meant giving up my independence. Not on my life,” Henri Dauman summed up, suddenly very serious. While he admits that such a contract would have gained him great notoriety, sacrificing his autonomy was never an option. He might as well sold his soul to the devil. “It affected me and led to reduced activity, but I have no regrets. I’m the happy owner of all my images,” he asserted.

“The whole science of photography is in the eyes”

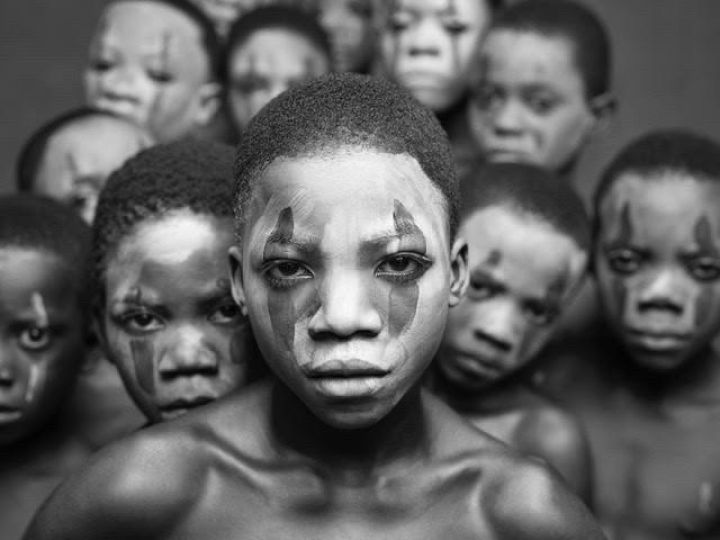

In the 1960s, Henri Dauman turned celebrity portraits into one of his trademarks. He bypassed the exercise of the “posed” portrait, privileging instead the “created moment”: a moment of true complicity, which brings out the deeper self of the subject, rather than his or her public image. Dauman photographed his models “frontally, in close-up.” “The whole science of photography is in the eyes,” he remarked. Seeking to capture an intimate moment, he would get closer and closer to his subjects. “Close enough to feel Fellini’s breath on my face,” he noted with a smile. Fellini was one of his masters, and Dauman risked sticking his lens right up to his nose just to get a reaction. The result was surprising. Fellini seems to be wondering where did the photographer get the gall to touch his face. “My assistant nearly choked watching me do this. But the result is quite interesting, don’t you think?”

Without any affectation, Henri Dauman immortalized Marilyn Monroe’s sex appeal against the reflection of cinema marquee lights at the premiere of Some Like It Hot. With similar spontaneity he captured Elvis Presley’s snazzy pout, the youthful figure of Alain Delon, the nude back of Brigitte Bardot whom he met during the shooting of Louis Malle’s film A Very Private Affair in 1961. The photographer caught the beautiful actress sitting in bed, bathed in natural light, lost in thought and gracefully nestling a lit cigarette between her fingers. Between shots, the reporter played himself on the set—a photographer lost in a crowd of paparazzi. There is a photo that immortalizes Henri Dauman and the 27-year-old star as she gives his Nikon, equipped with a 180-mm Zeiss lens, a caressing look. It’s a rare moment of camaraderie, as the photographer normally prefers keeping a respectful distance from his subjects once the shot has been taken, “so as not to be influenced.” A free spirit, as ever…

A modern narrator

In the 1960s, the modernity of photography depended in part on a skillful arrangement of photographs on the printed page. Henri Dauman took close interest in the work of magazine art editors. The TV industry was flourishing but this was still “the age of lead,” and Dauman was well familiar with the pitfalls of printer’s ink. But necessity is the mother of invention. And thus, “for the supplement to The New York Times, which normally came out on cheap newsprint, I got the idea of planting a small portable electronic flash behind the subjects, in order to throw more light into the portraits and make them come out better on the page. This lent added depth to the photo.” This technique has been widely used since by other photographers.

When Life Magazine assigned ten renowned photographers (including one Gordon Parks and Cornell Capa) to make an image illustrating the concept of loss of individuality in industrialized American society, Dauman produced his own photo experiment. “My image included rows of identical windows of a Park Avenue skyscraper, and three figures, fighting or falling, silhouetted in the foreground against red and green neon arrows.” His modern sense of narration received recognition, and the image was selected for the cover of the April 21, 1967 issue of the magazine. The similarity between this image and the opening sequence of the TV series Mad Men, representing a black and white silhouette of a man falling from a skyscraper, did not go unnoticed. “I think that they were inspired by my photo, but the series is so well done, I didn’t say anything.”

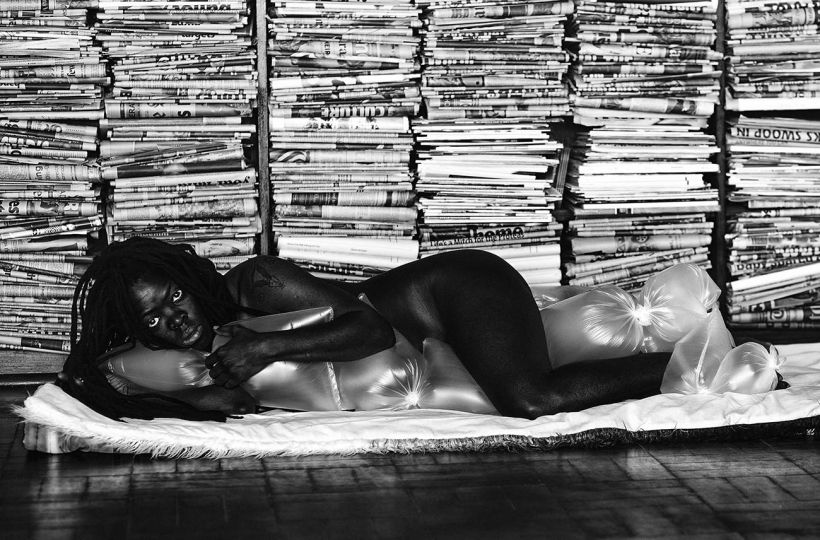

The quantity and value of his images today exceed the time and space Henri Dauman is able to invest in them within the four walls of his apartment. He dreams of having some foundation or an American university offer the archival space and digital resources this future heritage deserves. At home, he has thousands of negatives, as many contact sheets, and hundreds of vintage prints just waiting to be discovered. “Less than 1% of my archives have been exploited,” he points out. His pictures of artistic avant-gardes alone—he was among the first to photograph the minimalists and early Pop Art—are worthy of an exhibition. Or a book. “I was the only photo reporter to cover the Pop Art exhibition The American Supermarket in 1964,” he stated with a sparkle in his eye. These photos reveal the boyish face of as yet unknown Andy Warhol, and his early reproductions of Campbell’s soup cans.

While he acknowledges the “magazine” quality of his photos, Henri Dauman makes no distinction between images hanging today in museums and those made yesterday for the printed page. “Originally, my photos were not made to be exhibited. Seeing them on a wall is disturbing,” he declared upon visiting his very first exhibition, conceived by Vincent Montana, Henri Dauman’s producer and friend, and curated by François Cheval and Audrey Hoareau at the Palais d’Iéna in Paris in 2014. These photographs, which yesterday were sized to the page of a magazine, are now taking on a new life.

Guénola Pellen

Guénola Pellen is editor-in-chief of the magazine France-Amérique, a French-language publication in The United States. She lives and works in New York, USA.

Henri Dauman, The Manhattan Darkroom

February 11 to May 21, 2017

Musée Nicéphore Niépce

28 Quai des Messagerie

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

France