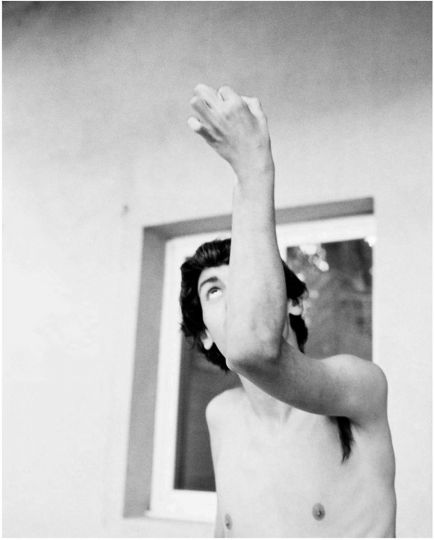

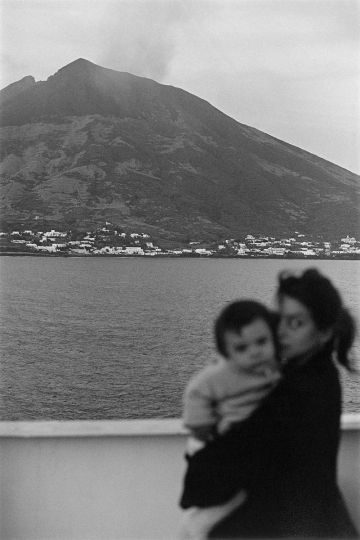

In more than 200 stirring portraits of French writer and photographer Hervé Guibert, Hans Georg Berger delivers a passionate homage to an author who in his books redefined the genres of fiction, criticism, autobiography, and memoir. Guibert died at the age of 36 of AIDS; Berger photographed him for almost 13 years. A singular and daring project of photography united both of them: exploring the limits of conventional notions of the portrait and self-portrait, and ultimately of authorship. With the sweeping radicalism of young artists, they set to a task which now this book reveals. It speaks of beauty, of gay love, of the experience of writing, of photography, of great cities and of a mysterious voyage to Egypt. It speaks of images of phantoms and of paradise.

Between the two young photographers, the complicity was such that Guibert asked: “Would they not be self-portraits? Hans Georg Berger makes me into the protagonist of a biography which he seems to invent, which at the same time is my own.”

At the beginning of the photographic dialogue between Hervé Guibert and Hans Georg Berger was Guibert’s literary and personal confrontation with photography his book Ghost Image. It is a collection of 64 brief observations and fantasies that revolve around photography’s functions and effects. What emerges from this oscillating inventory is a surprisingly precise picture of what Guibert expected of photography, expectations that manifested themselves in the photographic dialogue with Berger over the following thirteen years. The book can be read as an experimental literary layout for the joint photographic work with Berger. In Berger he found a congenial counterpart who shared his visual perceptions and with whom he celebrated a long-running enactment in hundreds of photographs. The resulting photographs are as radically personal as the vision in Ghost Image is subjective.

The dialogue with Berger was designed so that the interchange of perspectives could also be accompanied by an exchange of cameras. The fluctuation of the image ideas corresponded to the possible transfer of the artistic tools, which led to a commingling of what in any case were related aesthetic concepts and to a blurring of authorship.

Nevertheless, it is apparent that the weight was not equally distributed, that the driving force in fact came from Berger’s side. The quantity of portraits that Berger took of Guibert had an obsessive character, such that Guibert, who himself was obsessed with literary declarations of his own obsessions down to the minutest detail, could not help but extensively comment upon it: “Off the top of my head, I cannot think of such an example of assiduousness in the history of photography. And to start, what type is it: amorous? clinical? compassionate? envious? The dictionary teaches us that one speaks of the assiduousness of a doctor with respect to an ill person, an admirer with respect to a woman, a student or employee with respect to their work. […] But assiduousness in the history of photography is far more a social category (Lewis Hine’s workers) or an erotic one (Bellocq’s prostitutes), it zeroes in on a project (Sander’s recording of humanity) or an innate approach (Irving Penn’s White Cube). It seldom remains with one subject: it is more global than individual.”

For Guibert as author, this perspective was due to a spiritual kinship that included literature along with obsession: “Hans Georg Berger’s obsession about a single individual, close and familiar to him, seems to me more novelistic than photographic.”

Beneath the title “Return to the Beloved Image,” Guibert outlines a dialogue in Ghost Image that revolves around the suspended desire in the photo:

“Why did you photograph me so much?”

“I don’t have the impression that I photographed you a great deal. I certainly photographed you less than I wanted to. […] I photograph you as if I were stocking up on you, in anticipation of your absence. These pictures are like pledges, or bonds, for my desire: I don’t even know if I’ll ever print them, but if one day, because I am in love, your absence becomes unbearable to me, I know that I’ll be able to turn to this little roll of film and develop your image, and caress you […].By taking your photograph, I can attach myself to you, make you a part of my life, assimilate you. And you can’t do anything about it.”

Granting permission to be photographed by Berger is Guibert’s admission that he enjoys the role of the one who wants to be remembered because he wants to continue to be loved, even in his foreseeable absence. The willingness or even the expressed desire to be photographed when, ravaged by Aids, he no longer looked like how his friend wanted to remember him, goes far beyond this. With these pictures he consciously assumed control of the future of his self, one he would not live to see.

(from the introduction, by Boris von Brauchitsch)

Hans Georg Berger:

Herve Guibert, Phantom Paradise. A photographic love

Serindia Contemporary, Chicago

ISBN 978-1-932476-93-4