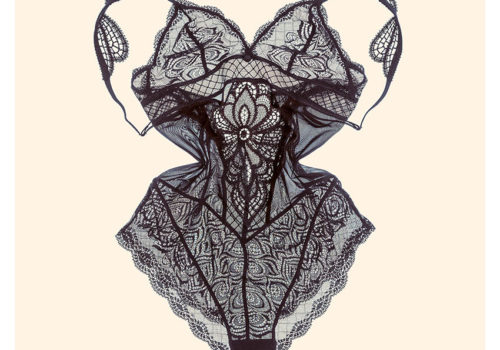

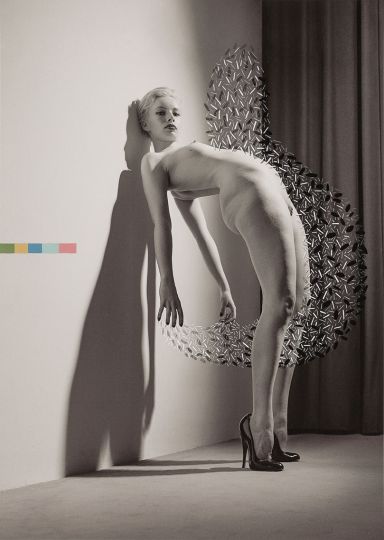

When he photographs nudes, Berquet apparently choses women possessing “classical” beauty. It would seem, then, that we’re back to the beginning, on the assumption that, from the first pornographic film in the history of cinema—tinted blue as if to lessen the charge—Eros keeps returning always in the same form. Nothing could be less true: Berquet lays bare the concept of the nude using fetish models and objects. He isn’t trying to do weird things while repeating that “Art must be beautiful.” He creates art by working like a maid in a hotel who came to photograph the traces left by the guests or to surprise them in their underwear.

Berquet is to Eros what the Ramones are to Bulgarian Voices. But the perfectionism of the shots brings to mind Mozart. The photographer goes light on special effects, tricks, and gimmicks that might keep sexuality at bay, if you will. His work is like a union between Sophie Calle and Chris Burden if they were in love. But instead of injecting art into the everyday, he reverses the hierarchy following a very precise scheme. A woman crawls on her belly, her high heels in the air, but this is far from any “performance.” The emphasis is on a particular idea of dream, namely a dream in which one is in danger. The photograph becomes an Eater of Souls, not with its spirit, but with its perilous dreams.

Jean-Paul Gavard-Perret

Jean-Paul Gavard-Perret is a poet, critic, and communications lecturer at the Université de Savoie in France.

http://www.gillesberquet.com/