Getty Images has pulled off a masterstroke by purchasing, for under 100 million dollars, its competitor Corbis via a previously little-known Chinese agency. Anti-trust law has thus been cunningly and legally circumvented, since the official buyer is United Glory, a Beijing-based entity which is part of Visual China Group founded in Shenzhen, China, in 2000, and which has represented Getty Images for ten years.

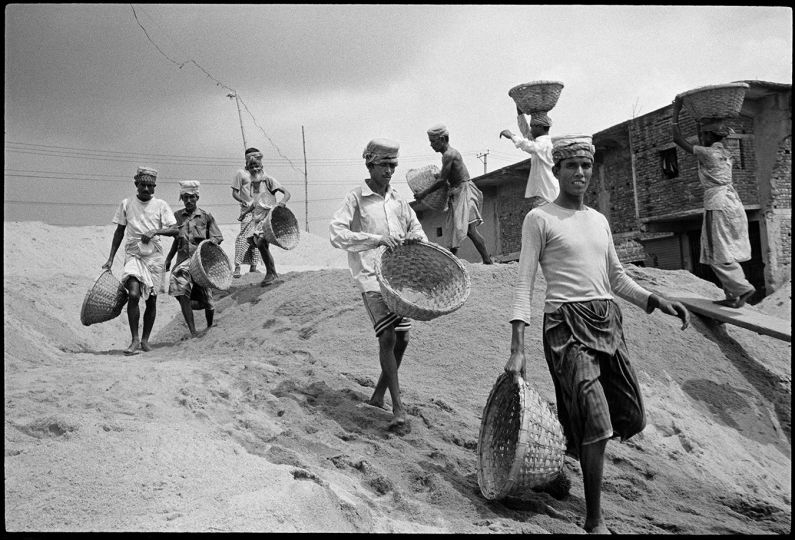

We have come full circle. There are nearly 200 million images and videos presently available to Getty’s customers. The content featured exclusively on the website gettyimages.com, includes all types of photographs, going back to the very dawn of the medium. The Hulton Archive previously acquired by Getty is a collection of 80 million images. Getty’s current visual content alone, following the takeover of numerous agencies, including Gamma Liaison, offers some 30 million photos. Corbis in turn had acquired 16 million images from the Bettmann Collection and 34 million from Sygma. When can we expect the acquisition of 20 million images from the six agencies represented by Gamma-Rapho? Such a merger would give Getty a spectacular boost, concentrating a near totality of world photographic production on a single website.

Following the buyout of Corbis and its subsidiary Demotix, Visual China Group has become the largest photo agency in China, where it already has relationships with 15,000 clients. The Group’s president, Ms. Amy Jun Liang, 49, asserted that the contract is to the advantage of all the parties concerned. VGC will guarantee exclusive distribution of Corbis–Sygma–Bettmann etc. photos in China, while Getty will offer the rest of the globe an extensive selection of photos reproducible in the press, book publications, advertising, videos, games, etc.

On the local scale, Visual China has thus become a powerful rival of the official press agency Xinhua which will find it hard to dominate the growing Chinese market.

In the course of prolonged and secret negotiations, the largest photography collection in history has been assembled right before our eyes, and its treasures are now freely accessible to all.

The only drawback is that, due to censorship in China, some banned images, such as photos from Tiananmen Square, will be blocked on the Chinese website but available elsewhere in the world.

The sale of Corbis will not impact artists, declared Greg Peters, a Vice-President at Getty, since current distribution agreements will be renewed under the same conditions. Artists who do not wish to participate in this new venture will be free to regain legal control of their rights. The future of the employees whom Corbis has maintained in France is, at this point, uncertain. However, Getty has already announced that the archives of Sygma and Corbis France will continue to be stored in a bunker in Normandy at an annual cost of nearly 200 thousand euros.

It may be even possible that this concentration of images will finally lead to the imposition of reproduction rights more realistic than those currently in force. In any case, the enormous distribution mechanism now synonymous with Getty will certainly be beneficial to photographers who decide to continue their collaboration with this new giant.

Corbis, founded by Bill Gates in 1989 as Interactive Home Systems and renamed Corbis in 1995, was created with the intention of constituting the largest online photo bank in the world. The dream of the world’s richest man did not come true, however, because Corbis was quickly outpaced by Getty—founded in 1995 by Mark Getty, a grandson of an American billionaire. Getty subsequently, in 2008, sold off its multiple acquisitions, under the name Getty Images, to an American investment fund, Hellman & Friedman, for the trifling sum of 2.4 billion dollars. Four years later, Getty Images changed hands a second time, to the tune of 3.3 billion dollars, to come under the ownership of the Carlyle Group, a company specializing in capital investments headed by Mark Getty and his long-time associate Jonathan Klein.

Photography has become a real business for investors. But is it really to the advantage of the photographers whose incomes have dropped more than fifty percent over the past ten years?