It may have been shockingly logical to proclaim painting’s doom in the 1830s, when the invention of photography revolutionized the potential of visual art. But French painter Paul Delaroche’s famous exclamation, “From today, painting is dead!” seems ironic now.

Rather than kill fine-art painting, photo-realism only liberated it, freeing it from the fussy dominion of perspectival studies, tromp l’oeil showmanship and painfully slow portraiture. As photography blossomed, so did painterly abstraction and experimentation, giving new life to art. Since Daguerre, all manner of visual media has thrived.

That’s the glorious insight immediately evident at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation, where Albert Barnes’ peerless collection of 19th-century Impressionist and early modernist painted masterworks now shares some exhibit space with only the second survey of photography in the Foundation’s venerable history. Smartly curated by Barnes President Thom Collins, “From Today, Painting Is Dead” draws some 250 early photographs from the private collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg. Collins arranges them with thematic clarity through several spacious galleries, guiding visitors along photography’s first journey, paralleling the tropes of the academic painting tradition it would eventually outpace.

Thus, the collection is organized by the official academic hierarchies of the ancien regime– from the primacy of history painting and on down the pecking order to portraiture, genre (or daily life imagery), to landscape and, finally, still life. For painting, such distinctions held sway for moral, religious and political reasons, but photography was at once embracing and questioning such convention, and fighting through technical limitation in the effort to match or best painting’s aesthetic dominance.

Landscape, for example, brought an immediate challenge, in that early photographers were unable to capture naturally lit terrain and sky in one image without an overexposed sky view. So it’s fascinating to see the elegant solution of Gustave Le Gray’s 1857 “The Great Wave,” an albumen print created from two negatives–one of the sea, the other of cloudy heavens, seamlessly wed in a single image: in essence, the first Photoshopped shot. Such ingenuity may not have been the rule in the early days, but the elemental beauty of these early landscapes stands out with great immediacy; and as the viewer moves from gallery to gallery, the rich variety and dimension of the medium’s early era makes a strong impression–especially since these collected specimens are of such high quality and in such excellent condition.

Collectors Mattis and Hochberg, on hand for the press opening of the show in late February, were rightfully proud of the depth and beauty of their holdings. “My hope is that a show like this will increase public awareness of 19th-century photography,” said Judy Hochberg as she reviewed the galleries. “Artists like Le Gray and William Henry Fox Talbot should be more well-known.” Michael Mattis noted the show’s aesthetic-fusion aspect: “The early interplay of photography and painting is important, of course, and it’s rare to see a survey of it on museum walls. Most shows of this kind have been monographic surveys. This is different.”

Curator Collins stressed the very modernist notion of “the anxiety with which photography was greeted by artists, though it would be nearly 50 years before technology evolved enough to approximate the work painters were doing in the 19th century.” To Collins, the span of the 1840s to 1880s was “the very fertile period”, when the pioneering photographers brought enormous energy and inspiration to the challenge, “grappling with the complex inheritance of official, state-sponsored visual culture.”

And so there is much to grapple with. The nuance of portrait painting challenged the long exposure times required by the first popular photo-portrait medium, the daguerreotype, but great glass negative portraits emerged, and the collection is rich with them – including several nude and erotic stereo daguerreotypes that convey the taboo-breaking determination of photographers to stretch the cultural (and commercial) conversation, along with treasures such as Auguste Belloc’s portrait of two Parisian sisters, hauntingly paired. And the many fine examples of Julia Margaret Cameron’s pre-Raphaelite pictorial portraiture, with her allegorical schemes and profiled subjects, is a breakthrough in photography–and for women in the arts.

The highlights are many. Fox Talbot’s original calotypes–from still lifes to portraits, landscapes and genre–push the medium forward in every way, while the early French masters, such as Eduard Baldus, Hippolyte Bayard, the Bisson Brothers, captured architecture and geographic iconography, along with Le Gray, Felice Beato and great showmen like Felix Nadar, who found dark beauty and gestured toward unflinching modernism in his views of the skull-lined Catacombs, strategically lit with artificial light. And his 1885 deathbed portrait of Victor Hugo points to the nascent power of celebrity photography.

Britain’s Roger Fenton, in a new vein, pioneered war photography with his images of the Crimean War. The collection has examples of his iconic 1855 “Valley of the Shadow of Death” imagery, in which the cannonball-littered landscape is mute testimony to desolation, as well as his 11-plate panorama of Sebastopol. And the sheer exoticism–to untraveled Western eyes–of the Middle East, Africa, India, Ecuador, Mexico, and New Zealand is on display in some of the earliest travel photography, helping to launch waves of tourism that would alter world culture.

There are some outside-the-box highlights as well that vault the survey toward 20th-century genius. From America, some examples of Alfred Stieglitz platinum prints are included–a stark treescape, “November Days” from 1887, and the genre portrait “The Letterbox” from 1894. And the numerous “photographer unknown” examples compete in their often-surprising way with the pedigreed output of Moulin, Nègre, or Hill and Adamson.

Indeed, a rare survey such as this is a testament to eclecticism and to the determination of passionate collectors and curators to do justice to a crucial period in the evolution of an aesthetic. Claiming gallery space in a venue as uniquely prestigious–if not sacred–as the Barnes speaks volumes for what Mattis and Hochberg have been doing. And Thom Collins’ organizational style and substance (part of a Barnes collaboration with University of Pennsylvania professor Aaron Levy, with curatorial contributions from students in Penn’s 2018 Spiegel-Wilks Curatorial Seminar) undergirds the project with taste, high scholarship and a strong sense of order.

Matt Damsker is an author and critic, who has written about photography and the arts for the Los Angeles Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Bulletin, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications. His book, “Rock Voices”, was published in 1981 by St. Martin’s Press. His essay in the book, “Marcus Doyle: Night Vision” was published in the fall of 2005.

He currently reviews books and exhibits for both the E-Photo Newsletter and U.S.A. Today.

Copyright iPhotoCentral

http://iphotocentral.com/news/article-view.php/0/261/249/1636/0/0/0

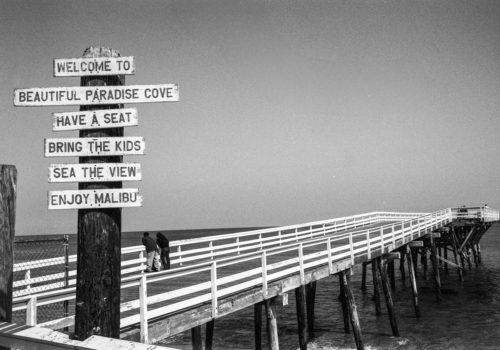

From Today, Painting Is Dead: Early Photography in Britain and France

Now through May 12, 2019

The Barnes Foundation

2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway

Philadelphia, PA 19130