The in camera Gallery in Paris presents a collection of prints by Frank Horvat focusing on women, including the famous portrait of a lady with a Givenchy hat. Made in a studio or outdoors, the photographs always contain an element of surprise, and show Horvat’s taking liberties with visual codes.

“I photographed fashion with bad conscience,” says Frank Horvat, who is about to celebrate his 90th birthday. This is not a confession, since this polyglot has never concealed his passion for photojournalism, so dear to Henri Cartier-Bresson. He even adds, with a beaming smile, “I would have liked to be just like him.” Like HCB, he traveled a lot and for a time was a member of Magnum.

He moved to France in 1956 and had his first photographs published in Jardin des Modes, a magazine founded by Lucien Vogel in 1922. Fashion was a natural choice for him in Parisian high life of Dior, Chanel, Grès… Dropping all formalities, Frank Horvat set the tone for this territory of frivolity, lending it, from the 1960s on, an energetic beat by adding a dose of surprise, a “godsend,” to his photographs.

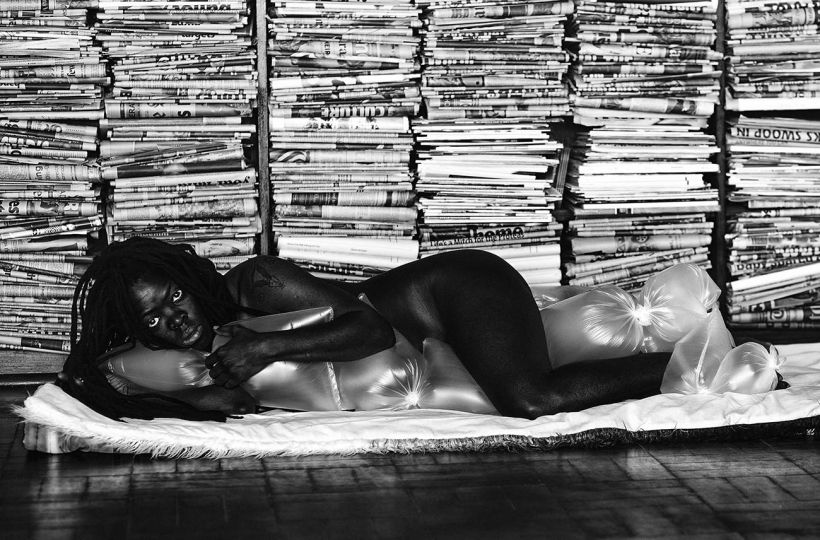

While he may not be the first to have embarked on the conquest of the street – we may recall the Hungarian Martin Munkácsi and his pirouetting models – Horvat is one of the few who have enjoyed it. He felt ill at ease in the studio; he was bored with stage sets as well as with some of the models, too preoccupied with the mirror. As he comments, “Photographing Miss Universe or her avatars is of no interest to me. Beauty is a stupid criterion, defined by an absence of flaws women believe they can cover with makeup. But it is these very flaws – an upturned nose, wrinkles, a small scar – that constitute true beauty. I didn’t want models to be beautiful; I wanted to make them beautiful, I emphasized the imperfections.”

More than on seduction (“I would have liked to be a seducer, I would put on airs, but more than anything else, I was clumsy”), this man, thirsting after the absolute, plays on “restraint and difficulty. It’s a matter of scratching the surface of a rock, of digging deep into the matter, and of invading time until you find light.” Horvat’s point of reference is the light of the North, the light of Dutch painters, like the light bathing his own studio later on, where, he says, “there is no estheticism, everything is calculated to obtain the best light.”

Everything must conform to desire. The key is that photography must happen, just like that, almost unwittingly, not out of necessity: “Take for example these lovers on the Quai du Louvre in Paris: three seconds earlier I hadn’t seen them, I hadn’t foreseen I would photograph them, obviously. There you go, that’s what interests me, the surprise, not the drive, but recognition, that’s it, that’s the word. Recognizing something within myself, and recognizing something I have seen.”

This enemy of pretense followed his own imperatives, without attempting to please anyone: whether he was trying out a new telephoto lens at the Gare Saint-Lazare which he transformed into a panoramic ballroom; or capturing the alabaster body of a woman crossing the stage before the impassive gaze of a reveler; or was himself hypnotized by a young nude girl, turning her back holding a large sheet…

Women are present throughout Frank Horvat’s life just as they are in his photographic archives. They are neither prey nor trophy: “I am not one of those men who act like they’re on a golf course or out on a hunt. I’ve always preferred the company of women, including in my photographs, and courting them just wasn’t on the agenda.” While he is saying it clear-sightedly, he did fall in love with certain sculptures by Degas, patiently immortalizing their patina-covered miniatures. This work was imbued with discreet, deep-felt sensuality – his trademark.

Brigitte Ollier

Brigitte Ollier worked for 30 years as a photography critic for Libération and is now an independent writer.

Frank Horvat: Please don’t smile!

March 15 to May 19, 2018

in camera

21 Rue las Cases

75007 Paris

France

www.incamera.fr