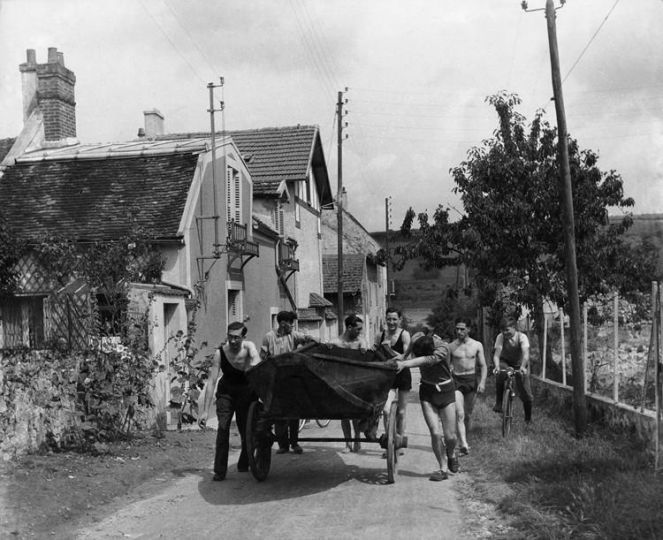

Gilles Peress – Forced Separation, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1993

In Gilles Peress’s photograph “Forced Separation, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1993,” family members are forced to flee while others are left behind during a conflict marked by ethnic cleansing, rape, and mass killing. Eric Stover, the Human Rights Center’s faculty director, worked with Peress during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia and its aftermath. This photo, Stover says, captures the anguish of families being torn apart and the uncertainty of not knowing whether it is safer to stay or to go.

Gilles Peress raises the dilemma of human rights photography:

“I keep asking myself the fundamental question: Can human rights photography, like 18th century novels, be a vehicle for empathy? Can photographs motivate viewers to engage with human rights issues and bring about real change? As we know, badly used photography can be a vehicle for propaganda or emotional exploitation of the worst kind, and can ultimately desensitize viewers. Alternatively, if we accept the postmodernist argument mentioned above, we run the risk of photographs not being taken and entering a black hole of not seeing and a complete absence of consciousness. Which do you choose?”

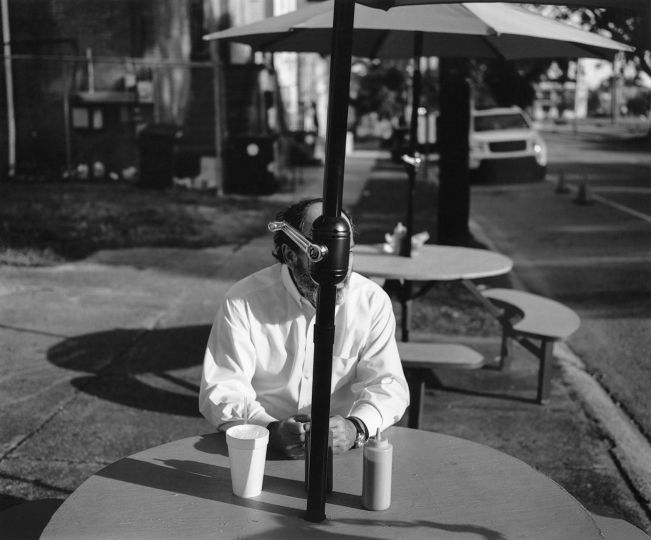

Thomas Morley – Rose Lakue, Uganda, 2005

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), led by Joseph Kony, ravaged northern Uganda from 1986 through 2009. The LRA abducted children to be soldiers and sex slaves, massacred villagers, and displaced more than 1.7 million people.

The LRA killed 65-year-old Rose Lakue’s husband, abducted her eldest son, and burned down her home.

Photographer Thomas Morley and HRC’s Eric Stover traveled to the Amida camp for the internally displaced and other camps in northern Uganda to document the violence. They interviewed and photographed survivors like Rose who were willing to tell their stories.

Writes Thomas Morley:

“Outside the Amida camp, under a stand of trees, I set up a wooden chair and sent a messenger inside to see if anyone was interested in having their photo taken. Over the next two days, to my utter surprise, dozens of women appeared in their best clothes, wearing what little jewelry they possessed. Younger women helped older women to sit under the trees, waiting, in turn, for me to take their pictures. I was awestruck and humbled by their quiet dignity and courage and by their determination not to be forgotten.”

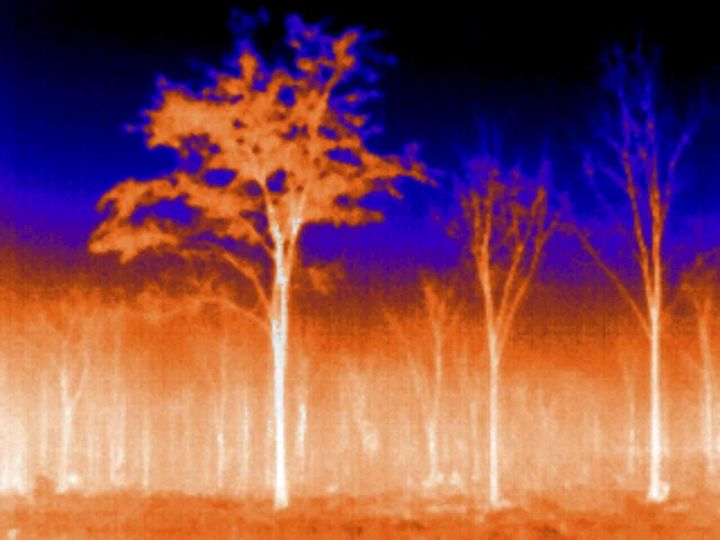

Jean-Marie Simon – Religious Procession, Nebaj, Guatemala, 1982

During the 1980s Jean-Marie Simon documented the violence perpetrated by the Guatemalan army on largely indigenous populations in what was called a “scorched-earth” campaign. Over three decades some 200,000 Guatemalans were killed or disappeared. Simon photographed both brutality and beauty–often side by side.

Writes Jean-Marie Simon:

“In the early 1980s, I traveled throughout Guatemala at the height of President Ríos Montt’s “scorched-earth campaign” against indigenous communities suspected of sympathizing with the guerrillas. Most of my photographs depicted scenes of violence and destruction, but, occasionally, I paused to capture moments of ordinary life. The portrait of the Ixil schoolgirls was taken just after photographing the bullet-riddled corpses of four men suspected of being guerrillas at the local army garrison up the street. Dawn was taken in Nebaj, Quiche, during a trek over the mountains to Acul, a neighboring Ixil village where the Army had killed 46 men, separating them into groups called “Heaven” and “Hell.” Those who went to “Heaven” were forced to bury those who went to “Hell.” I took the photograph of a solemn feast day procession in Nebaj two years after the Army had subjugated that population into a choice of submission or death. Photographing moments of tranquility and amity in the midst of a civil war may seem pointless—I certainly thought so back in 1980. But I later realized that those same images stood as a stark counterpoint to the brutality of the Guatemalan conflict by honoring the poignancy and dignity of a people under siege.”