The exhibition which opened on Sunday 2 December 2019 at the Lycée des Jeunes Filles Ba Aminata Diallo was one of the highlights of this opening week. With the exhibition site inside the school grounds, hundreds of girls were able to attend the opening ceremony.

It was invigorating, perhaps even moving, to see members of the international art scene mingling happily with all these young girls in the same room in effusions of joy, excitement, and curiosity. Particularly when we know from the speech of the general delegate of the Bamako Encounters, Igo Diarra, that the space which today serves as an exhibition space was, several years ago, the refectory where his mother came to eat when she was herself a high school student.

Photographing themselves tirelessly in front of the images on display and with the visitors who came specially for the opening of the exhibition, the excitement was perceptible among the young girls. By taking over this place, the curatorial team wanted to shed light on the artists on display but also on the young students and the future they embody for Mali. As co-curator Astrid Sokona Lepoultier aptly says, “If young people don’t come to the Bamako Encounters, then it’s up to the Bamako Encounters to go to them”.

The palpable happiness and pride in the young girls at the opening of the exhibition in their establishment bodes well for the development of an interest in art and photography and for potentially giving birth to vocations in some. I remember one of them, who, fascinated by the images, read one by one each of the cartels that accompanied the works on display, then who took a meticulous photo first of all the image presented, then the cartel referring to it, so as not to miss anything and be sure to keep track.

The exhibition brings together the works of Nirveda Alleck & Katia Bourdarel, Dickonet, Halima Haruna, the Iliso Labantu collective, Rahima Gambo, Guy Wouété, Harun Morrison & Helen Walker and Santiago Mostyn, as well as the special project by Fatima Bocoum “Musow Ka Touma Sera” (“It’s the Era of Women”). The latter presents the photographs of 6 Malian artists, namely Fatoumata Diabaté, Amsatou Diallo, Fatoumata Diallo, Fanta Diarra, Oumou Traoré and Kani Sissoko, bringing a lot of thoughts and keys to open a dialogue with the young girls.

Indeed, a wide range of subjects was tackled through the works selected to establish didactic content and promote reflection, particularly in the complicated period that adolescence can represent. The works presented become real tools of reflection for teachers and young girls of the school.

For example the question of memory, and that of how to take over in the face of tragic events addressed by Rahima Gambo in her work A Walk, which she designed following the suicide bombings perpetrated in the North- east of Nigeria at the University of Maiduguri in 2017. But also the questions of expression and language and the idea of giving voice to the unsaid using the mystery are found in the video Breathe, by Nirveda Alleck and by Katia Bourdarel.

The importance of the collective and the notions of sharing, living together and creating synergies that are linked to it appear in the work of the Iliso Labantu collective. This collective from South Africa started from the premise that there were few township photos taken by the township residents themselves and wished to remedy this by “training residents to use photography as a tool to document their lives “and to be able to embark on a sustainable career as professional photographers in the townships of Cape Town”.

From another angle, the idea of the collective was also approached by the Musow Ka Touma Sera exhibition (“It is the Era of Women”), one of the winning exhibitions of the apexart open call, in which the work of 6 Malian women artists came together to denounce the principle of Sutura, a tacit cultural norm that psychologically prepares women and girls to conceal, forgive and endure their suffering. This exhibition has its place in a high school for young girls, to invite them to reflect on their femininity, so that they can defend and claim it but also so that they are not afraid of speaking out. Fatima Bocoum, curator of the exhibition thought out this exhibition to “break the restrictive cultural norms that govern the lives of women in Mali” so that “femininity is no longer synonymous with tolerating pain but rather with the ability to fight for justice and equality where it should be and despite adversity.” For her, the solution lies in “a feminism stripped of all ambiguities and all cultural relativism”.

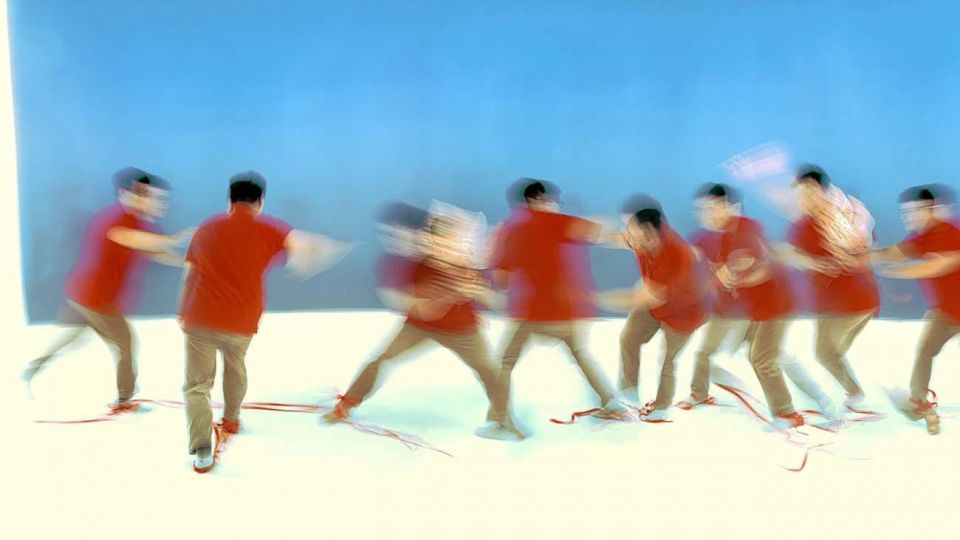

The notion of identity is also discussed several times, for example with the work of Santiago Mostyn and his film Altarpiece, which takes into account “the fragility and the potential of the black body in two distinct political spaces: late capitalism in the United States and postcolonial populism in southern Africa and the Caribbean “or Guy Woueté who in his series Terre & Faces, opens a” reflection on exotic iconography and the perpetuation of stereotypes produced within the framework of civilizing missions justifying colonization and others invasions. How can we create our own image when it is imposed on us by a colonising gaze”. This is an important subject to tackle with young adolescent girls who are building up their identity.

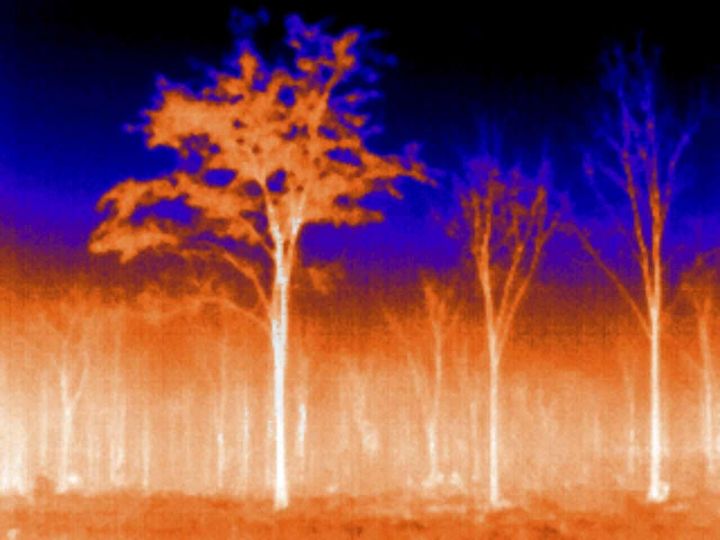

But also the relationship of Man to Earth, the environment and his ancestors as in the video Other Side of the Creek, by the young artist Halima Haruna, “a para-fiction of the petrochemical industry in Nigeria through the discovery and reappropriation of the spiritual self”. There is also the Malian Dickonet who presents the video Djoliba, Niger River, whose speech focuses on the importance of respecting the environment and in particular the Niger River, a river that has nourished the country for a long time.

To conclude, the overflowing reactions of enthusiasm and curiosity that I saw during the opening of the exhibition are a very promising sign of a strong interest on the part of young girls towards the Bamako Encounters. It is in particular at the Lycée des Jeunes de Filles Ba Aminata Diallo that the African biennial of photography seems to have taken its full meaning.

Anna Reverdy