“Eastern cretins,” my father used to say. “Two thousand years of cretinism.” Over the years, I discovered that the least Christian among the cretins, that is, my father, was just a little bit Christian after all. He baptized me, enrolled me in a Catholic school, and he wants to end up in the Père Lachaise cemetery, in a coffin, with a tombstone and a cross. I even think he will make us attend a mass after his death. Like my father and mother, I too am a Maronite. It’s a burden. And a gift. Being an Eastern Christian means being accepted everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It means being at home in Europe and in the Middle East as well as being out place everywhere. It means being always a bit off the mark.

The expression “Eastern Christian” (“chrétien d’Orient”) is originally French. It was first used in the nineteenth century to define populations inhabiting the territory spanning from Turkey to Iran. The exhibition Chrétiens d’Orient: 2000 ans d’histoire at the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris focuses in particular on the “Holy Land” and the present territory of Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. This area, in turn Roman, Byzantine, Muslim, and Ottoman, before witnessing Arab nationalist movements, is today a key concern and the source of many news headlines. There is no need to enumerate them.

From Byzantine and Ottoman icons, to monastic jugs decorated with the Last Supper, to the first printed works in the Arabic language, two-thirds of the exhibition are replete with frescos and relics, unique items never before exhibited, such as the Rabbula Gospels, an illuminated paper manuscript found in Syria, dating to the sixth century, and containing the first representation of the Crucifixion as it is passed down in the gospels. Christ is both human and divine. Blood drips down his royal mantle. At his side the Virgin weeps.

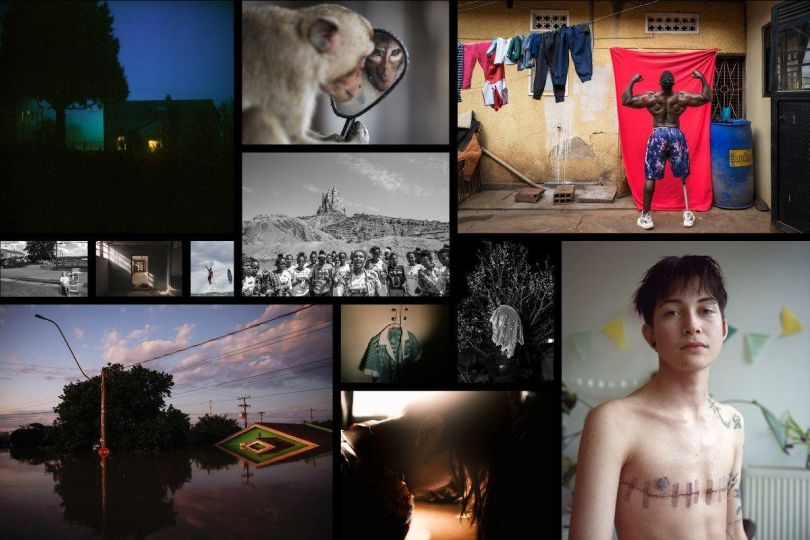

“Some people can see her, others can’t. There is perhaps a message in all this,” said the mother of the filmmaker Namir Abdel Messeeh in his film The Virgin, the Copts and Me (2011). In 1968, a year after the Six-Day War, popular fervor that followed the manifestation of the Virgin Mary in the Zeitoun district of Cairo testified to the need to turn to a protective figure. There are other images accompanying an excerpt from the film. The final portion of the exhibition focuses on photography and video. In Lebanon, Syria, and Egypt, the photographers Houda Kassalty, Nabil Boutros, Katharine Cooper captured altars, pendants, icons, objects associated with the Virgin, Christ, and other saints that decorated the streets and interiors. These objects signal a presence as well as protect. Like in the images by Hawre Khalid where protection is guaranteed by weapons wielded by Christian militia in Al-qosh, in northern Iraq. The town has never been taken over by ISIS.

The history of Eastern Christians is multifaceted. The writings diverge and so do points of view. The artist Dor Guez commented in an interview with the magazine Exerbiner: “I think that the only way to read history is to tell personal stories, since every official narrative is advanced by vested interests and within a certain national context. I think that through the personal point of view, we can move beyond that.” Born to a Christian Arab father and an Israeli Jewish mother, Dor Guez tells his own story through family images, and through his story, that of a people, a country, and a region. Following this photographic project, he created the Christian Palestine Archive (CPA), the only archival institution of the community. For a minority within a minority, often forced into exile, archiving has become a weapon used to ensure the continuity of memory. The clan images of the Azeizait de Mâdabâ preserved in a French Bible archeology school are part of the same struggle.

Being an Eastern Christian is no a big deal. It has about as much or less importance than being (Eastern) Jewish or Muslim. I don’t need to pin the letter “N” (for Nazarene) in Arabic to my jacket unless I also display “J,” “M,” and “A” (for atheist). As Amin Maalouf wrote in In the Name of Identity: Violence and Need to Belong, “To imprison oneself in a victim mentality can do the injured party even more harm than the aggression itself.” The next best thing, as Roger Anis’ images of newly-weds show, is to live one’s life as if things were normal. Or just about.

Sabyl Ghoussoub

Sabyl Ghoussoub is a journalist and a photographer. Between 2011 and 2015, he was the director of the Lebanese Film Festival in Beirut.

Chrétiens d’Orient: 2000 ans d’histoire

September 26 to January 14, 2018

IMA – Institut du Monde Arabe

1 rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard

75005 Paris