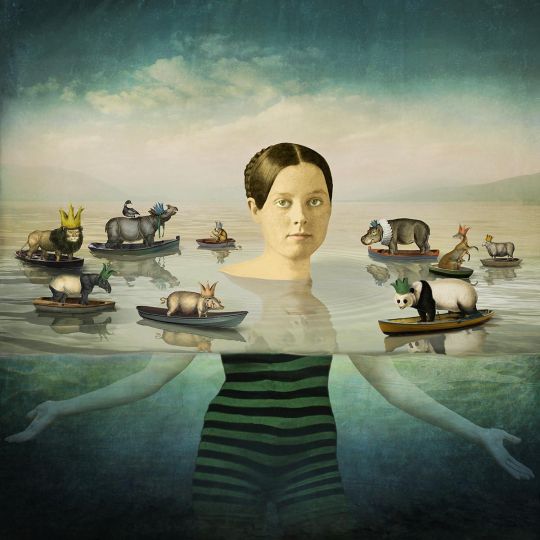

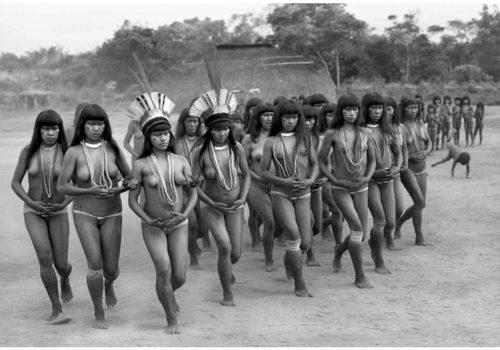

The “capture” of an animal, a living creature , has posed a technical challenge in photography since its beginnings. From the creators of daguerreotypes to the pictorialists, there were many whose subject was the creature, often a very human one.

Very shortly after the official birth of photography in 1839, the main technical challenge facing pioneers of the medium (chemists, opticians and artists) lay in trying to capture living subjects. A human being can stay still by choice; early portraits show individuals with fixed grins, frozen for several minutes in uncomfortable poses. The behaviour of animals is more unpredictable, even when domesticated. A whole arsenal of devices was therefore deployed to make animals hold a pose: the use of leashes, the installation of stands, the lure of a reward or the threat of punishment. Others preferred animals to be asleep, dead or even artificial!

Animals were ubiquitous in nineteenth century photography, in artists’ reference material, scientific studies, experiments with snapshots, illustrated reports and pictures with artistic aspirations in the tradition of genres such as portraiture and still life. These many and varied representations of animals reflect their position in a very strict hierarchy (ranging from the beast, such as the monkey, to noble creatures like horses and lions) and also a gradual change in status. There was a steady shift from animals as production tools, staple foodstuff, or “personal property” as enshrined in the French Civil Code of 1804, to the companion animal or pet, thus anticipating the recent definition of an animal under French law as a “living being endowed with sensitivity”.

Du coq à l’âne, L’animal dans la collection de photographies

From 20th February to 13th May 2017

Musée d’Orsay, Salle 19

1 rue de la Légion d’Honneur

75007 Paris

France