Snow fell on Dresden the evening before a ceremony commemorating the city’s catastrophic destruction nearly seventy years ago. On the night of February 13, 1945, Allied bombs claimed 25,000 lives, many of them civilians. Inside the reconstructed Semperoper opera house of the Saxon capital, the atmosphere was dignified. A very warm welcome was given to the recipient of the third Dresden International Peace Prize: the photographer James Nachtwey. Mikhail Gorbachev was honored in 2010, and Daniel Barenboim the year after.

As a white shroud covered the ashes of the past, a large and often emotional audience listened to Wim Wenders’ brilliant tribute to James Nachtwey, the director’s favorite photographer along with Sebastião Salgado. One could feel in the auditorium a shared sense of civil and professional commitment to the community.

Alain Mingam

Exclusive: A Tribute to James Nachtwey

If a war photographer is awarded a Peace Prize,

furthermore in a city once devastated by a war,

then he must be a very special person

and a truly extraordinary photographer

who has something to oppose to war.

For it is the nature of war

to engage and take in everything,

to occupy and appropriate, without exception.

Which war film, for example, isn’t, deep down,

a glorification of war,

even against better judgment,

and often even in spite of the best of intentions?

And: It is in the nature of images of any type

to represent what they depict.

“What you see is what you get.”

That’s exactly what makes them so very powerful.

It’s almost like trying to square the circle

if you want to dissociate yourself

from what the image depicts and conveys,

let alone trying to tell the opposite of what it shows,

War is a huge, infernal industry,

the largest one on this planet.

It seems presumptuous

for one man to try to

stand in the way of this machinery.

Once war has broken out,

everything spirals out of control almost immediately,

turning even the armies and the soldiers who fight in it

into helpless onlookers,

victims of their own hubris.

Who would dare then to oppose it and put it into perspective

with mere… photographs.

Who would seriously deploy cameras against tanks!

Just try to visualize it!

After all, almost all of us take picture today!

Even your cell phones don’t come without a camera any more.

Or perhaps you have one of those small, convenient digital devices.

Or you may even own professional equipment…

Just imagine going to war with that!

Imagine doing that just to take a picture

to undeceive the entire world, tell them what’s going on there,

a photo that would influence the outcome of the war

or even end it.

Right. That would be sheer madness!

All right then, imagine just this:

You want to change the life of ONE person with a photograph.

That alone is an enormous challenge,

if you think about it.

The short moment when you look through the viewfinder

or at the tiny display,

as you point the camera at something,

and finally press the shutter button…

that second is supposed to achieve something?

To capture something and thus captivate,

to move somebody, or even shake up the world?

How can that be possible?

Who do you have to be to attempt such a thing?

How… would you go about it?!

James Nachtwey’s images give us an idea

of how he “goes about it”,

in the true sense of the word:

where others “just want to get out of here”,

that’s where he goes.

He travels, in principle, in the direction of places

that other people are only leaving from,

or have already left,

or can’t leave anymore.

It is with that first movement

that he’s already opposing war:

With himself.

With his safety,

his life,

his affection,

his conviction.

All of the above are captured in any of his images…

“Wait a minute!…” you may object.

“Perhaps he gets a kick out of this going-to-war thing,

or maybe he is some kind of thrill-seeking tourist.

After all, there are people who climb up skyscrapers

or walk tightropes at dizzy heights

or hurl themselves out of planes or jump off bridges –

things which none of us would do,

but which a few others apparently like to do.

Couldn’t Nachtwey be one of those?”

If he were, he surely wouldn’t win a Peace Award,

he would just win some medal or an Action Prize.

This James Nachtwey may have the same first name,

but he certainly isn’t a James Bond type.

Who is he then?

I don’t think you have to know a photographer’s biography

to understand who he is.

He shows us in each of his pictures.

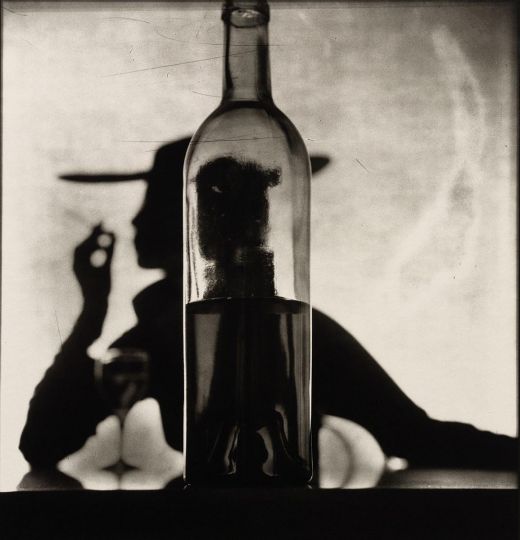

Each photograph also contains a second one, invisible at first,

that doesn’t reveal itself immediately.

It’s a “reverse angle”, if you will, a “counter-shot”

– which reminds us that taking photos is also called “to shoot pictures” –

yes, the camera is shooting back,

is literally “backfiring”.

The eye that looks through the lens

is also reflected on the photo.

It leaves a faint, sometimes shadowy

trace of the photographer,

something between a silhouette and an engraving,

an “image” not of his features,

but of his… heart, his soul, his mind, his spirits.

Let’s stay with the first and simple word for a moment, “the heart”.

The heart is the real light-sensitive medium here,

not the film nor the digital sensor,

it is the heart that sees an image and wants to capture it.

The eye lets the light in,

which is why we also call it a “lens”,

but it doesn’t “depict the image”,

it doesn’t “depict” anything.

Nor does the retina

or the nerve cords that transmit the information.

The “image” is created “within”.

There, it is matched with many other signals

that are coming in at the same time.

Some of these are related to formal or aesthetic criteria,

like to composition and focus,

to contrast,

to the overall impression and to details.

Other signals are of an ethical or moral nature.

What’s going on here?

What’s happening to the people in front of the camera?

What does their dignity consist of?

Or what is violating that dignity?

What is that image telling us?

Which case history lead to this moment,

and what continuation does it suggest?

How do I react to it as the one who is seeing,

as the one with the camera?

What is it about this image that touches me!?

Do I have the right to show it to others?

How will it affect other people?

Could what I see be possibly misinterpreted?

How can I prevent that from happening?

Would it help if I took a step forward or to the side?

If I stepped back a little more?

If I left this or that out of the frame?

There are a thousand signals and messages arriving simultaneously

all of which have to be processed within a fraction of a second.

The hands are already part of the thought process

as they correct the frame,

the finger already knows what’s coming and presses the shutter button…

What I’m trying to say is:

The photograph that’s just being created

includes all of these thoughts,

processes them as another kind of light, “an inner light”,

depicts them and “contains them” at the same time

that it deals with “the outer light”,

thus turning it into that “counter-shot”

the invisible portrait of the photographer himself.

And all of this isn’t happening at a birthday party,

or on a football field, or at a rock concert,

but in a war.

Everything is raw, tense, loud, cruel, out of control,

insane, incredible, awful, unfair, perfidious…

But that’s exactly why the photographer has to be

just as precise, quick, careful, considerate and dependable

as if he were at a wedding or on a Red Carpet.

No, that’s not true:

In fact, he has to be even more precise, quicker, more careful,

more considerate and more dependable.

In war, often enough, you don’t get a second chance.

The photographs exhibited in the Dresden museum of military history

represent a small selection of the many photos James Nachtwey

has taken in over thirty years as a traveler and documentarist.

They were taken in Afghanistan, in the Balkans, in Ruanda,

Chechnya, Darfur, at Ground Zero in New York and in Iraq.

This list could easily be extended to include images from Sudan,

from Northern Ireland, from Romania, and so on, and so on…

James Nachtwey was in “the heart of darkness”,

to quote the title of Joseph Conrad’s famous novel.

If ever someone actually was there, it’s him!

One might think that this darkness shows through,

that its grim, depressing reflection makes its way

through the photographer’s eye,

weighing down his heart, his soul, his mind, his spirit.

And indeed, very often that’s exactly what we feel

in TV documentaries, in newspaper images, in magazines,

that the atrocities we see depicted

have hardened the photographers’ hearts.

We can often tell that he was already looking the other way

while he was taking the picture,

was already done with all that death, starvation and fear around him,

was only thinking about himself, his own salvation from all this hell,

was no longer really WITH the subjects in front of his camera,

and no longer really watching death at work.

In all of James Nachtwey’s images we can also see at the same time

that he didn’t want to look the other way,

that he wanted to endure the sight and see exactly

what was standing or lying there before him,

that he knew he owed it to the people,

the dead, the starving, the sick,

the entire situation in front of his camera,

that he’d see and show it as exactly as possible.

If someone’s dignity has been violated

he doesn’t violate it a second time,

as a voyeur would—

but he restores it.

Now, am I just making this up,

or do I have something to back up my impressions?

I believe that all we really have to do is take a closer look.

All we have to do is train our eyes to see

not just the PHOTOGRAPH itself,

but the ATTITUDE of the man who took it.

Every look represents a certain attitude or state of mind,

YOUR gaze just as well, at any given time.

Interest, boredom, disgust, indifference,

sorrow, love, surprise, curiosity, hatred,

affection, respect, aversion, exhaustion, frustration…

whatever guides our eyes

is depicted along with the subject

when a camera is lifted to the eye.

There is no picture that was taken without an attitude of some kind or other.

And nowhere is this more necessary

than when you stare death in the face,

when you’re confronted with violence, despair, the abyss, the darkness.

The attitude of James Nachtwey the photographer

you can make out and decipher in each and every one of his photographs.

It is no secret.

I’m just picking an image of his

one at first glance isn’t all that warlike:

Three children, little girls, are standing behind a tree.

They’re covering their eyes with their hands.

Some distance away a helicopter is landing or lifting off,

clouds of dust swirling around.

We immediately recognize these helicopters.

There are usually guns protruding from the fuselage,

and indeed, there they are!

These roaring bumblebees are bringing troops, weapons, bombs…

in short, war from above, out of the blue,

and just as quickly as they came, they’re gone.

You immediately hear the “Ride of the Valkyries” from “Apocalypse Now”…

The children are everything but Valkyries.

Their colorful clothes, the slippers on their feet,

or the little one’s innocent best Sunday shoes and socks

all tell us how ill-prepared they are for

what is coming their way, inevitably,

or what is leaving them behind, possibly,

like astronauts would arrive or leave on a distant planet.

A few moments ago the girls were scampering around, laughing,

without a care in the world, …

and then came the invasion of the foreign gods.

The photograph invokes what may happen next

or what just happened.

Whichever the case, these children will remember this moment

as long as they live.

The caption that I’m turning to,

after I have tried to decode the picture myself for a long time, says:

“El Salvador, 1984.

The army evacuates wounded soldiers

from a village football field.”

Well, this explains it a bit.

Still the message of a photograph is only the photograph itself.

In museums many people pounce on to the caption

before they even look at the picture.

It’s as if they were trying to protect themselves from the image.

Reading creates distance,

the information lets you stand above things again.

I ask you urgently:

First read the photographs closely,

also here, in the Dresden museum of military history.

Then you will realize in this case:

There’s a lot of tenderness in this photograph.

This photo was taken by someone who is more interested in the children

than in the troops and their business.

It’s not a subject you would expect to see in a picture

taken by someone who went there to photograph the war.

To find this, you have to be on the children’s side.

You can’t cover your own face with your hands

and try to protect the lens of your camera from the dust.

You have to do the opposite:

open your eyes wide and risk the dusk in your face and your lens.

I’ll move on to another image,

almost the opposite to the one before.

The Balkan Wars.

It shows a truck unloading its horrific cargo:

dead bodies are sliding down from the bed.

The driver is leaning out the window of his truck

so he can see where he is dumping his load of dead men.

Among the bodies there is a wheelbarrow,

in a moments it will also come crashing down…

The dead are all fully dressed.

The way they’re sliding down the tilted surface,

with their heads dangling,

shows that rigor mortis hasn’t set in yet.

A hand is held up, partially covering the lens.

We see the palm of the hand, the thumb pointing down.

This is the right hand of a man

who must be standing with his back to the photographer.

This isn’t someone trying to stop the photographer from taking pictures;

he’s just motioning with his hand to direct the truck driver to the pit

that we know must be there, just outside the photo…

The most horrifying thing about this scene is

that it feels just like an everyday building site.

Do we even want to know which war this is?

Yes! The caption explains it:

“Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Bosnian army

has successfully held off a Serbian infantry attack

near the village of Rahic.

The bodies of Serbian soldiers who fell in the battles

have been brought from the battlefield

behind the Bosnian lines on a truck…”

James Nachtwey is extremely precise.

He is a witness,

and he takes this responsibility very seriously.

The word “eye witness” is fitting more than ever.

Someone who not only wants to describe what he has just saw,

but also wants to record it with words as precisely as possible

so that it can be used as evidence.

We can see that the image wasn’t taken at eye level.

The photographer didn’t look through the lens,

it was “shot from the hip”, so to speak.

As quick as a flash, before the man who raised his hand could turn around.

If he had turned around,

the image would have been a completely different one,

in fact, might have become impossible.

As with most of Nachtwey’s photographs,

the lens is a slight wide-angle.

With such a lens, the photographer has to be right where it’s happening.

To be able to take photos such as this,

you have to get close to the scene.

You can’t just easily zoom in from a distance.

The photographer himself has no distance, he is THERE.

And therefore we are, too,

no matter if we are sitting in our living room,

stand in a museum,

or hold a book or a magazine in our hands.

These are pictures by someone who has a strong desire for justice

in the face of the horror unfolding right before his eyes.

Someone who puts a lot on the line for this,

Even if the photo is being taken within the fraction of a second

by lifting the camera just a little more—

he still instinctively finds the right angle at the same time,

as if his hands were able to see…

With all his senses he is present and he is THERE!

Or let us look at a third image

taken during the Chechen War in the mid-nineties.

A village road, a singed wooden barn in the foreground.

On the snow-covered road in front of it lies a dead woman,

wearing a simple winter coat.

Beside her on the ground, a purse.

Sneakers and thick socks,

her left foot strangely and unnaturally twisted.

Is it broken, shot and wounded?

Around the corner comes another elderly woman,

cautiously, almost looking at the sight with curiosity,

“the neighbor”, the caption tells us,

a peasant scar wrapped around her head.

She stops in her tracks and stares at the frozen body in the snow.

You can almost see her thought:

That could be myself lying there!

There’s a hint of surprise in her stopping short, looking at the scene.

The simple, one-storey houses in the background

bear witness to the places’ poverty

There are shingles missing, or is that damage caused by the war, too?

Actually, we can’t help thinking

(or perhaps it’s more of a vague feeling

than a conscious thought:)

actually this photo is “just altogether impossible”.

Impossible because there’s something about it

that we can’t quite get into our heads.

In a movie, OK, we could accept a scene like this.

And then we realize what it is that we think is so “impossible” about it:

it’s the fact that the photographer is PRESENT

that he’s part of it, at this very place,

that he captured the neighbor right at the moment of recognition,

as if she were all alone at the scene,

as if there couldn’t possibly be another person with a camera

who’s not just watching, but creating evidence of the moment as well.

We are totally at a loss to explain the photographer’s presence.

How can he make himself invisible like this?

Unless he isn’t there as a photographer,

only there as someone else who has just rushed to the scene,

a fellow human being who is just as shocked, just as astounded.

Someone who has become so much as one with his camera,

that it indeed has become invisible to other people.

I’m also beginning to see something else

in each of the three images

that I just instinctively picked out, almost arbitrarily:

in these pictures the photographer doesn’t just see for himself!

And this is something you can not at all take for granted!

Actually, the act of photographing is a very lonely job.

You are left to your own devices,

especially when war is raging around you

or hunger and death are haunting the land.

But all of these photographs have one thing in common, an “attitude”,

the photographer’s awareness of standing where he is for others

of seeing on behalf of others,

of exposing himself, and of giving testimony, for others.

Who are these “others”

on whose “behalf” James Nachtwey goes to war, so to speak?

Are they just the subjects of his photos,

the starving, the dying, the dead, the perpetrators, the sick,

the injured, the sufferers, the horrified?

Or don’t these “others” also include us, the viewers,

the very moment we begin to get involved with one of his images?

When he makes himself a witness, and stands by this task,

doesn’t he call us to the witness box as well?

If this is indeed the case,

then James Nachtwey creates a community

between the subjects of his photographs

and us,

a community that we can’t get out of so easily.

He turns us into ONE humanity,

not more and not less: Common humanity.

The word “compassion” takes on its original meaning.

It doesn’t connote condescension or “pity”, “the pitying smile”,

but real empathy and true sympathy,

because the suffering of others is ours as well.

Nachtwey manages to see things

on behalf of both sides of humanity,

the victims and the viewers,

because his work is not just directed AGAINST war,

against arbitrariness, injustice and inequality,

it is, above all, intended FOR (and dedicated to) the people

he encounters in wars and in suffering,

as well as FOR US.

I am aware that the word I’m going to use is somewhat antiquated,

and it’s probably difficult to translate.

This man is a Menschenfreund, a lover of humanity,

and therefor an enemy of war.

And when he goes right to the heart of the war

he does so on behalf of us, in order to force us to look closely,

but also on behalf of the victims,

as the eye-witness who wants to testify in their favor

and belie war and its propaganda.

Maybe James Nachtwey is not just a photographer,

but has a lot of professions.

He is also sociologist

who doesn’t just dutifully record the phenomena and symptoms,

but who wants to understand what caused them;

a minister who knows that it is not consoling that gives consolation,

but most of all being there for someone else;

an archeologist who doesn’t just hastily burrow down into the dirt,

but who carefully uncovers stone by stone;

a poet who knows that he must never name things in plain words,

but only invoke them in the reader;

a philosopher who’d rather encourage people to think for themselves

instead of self-righteously doing the thinking for them;

a teacher who commands our respect

because he respects everyone, including himself;

a gardener who knows that you have to get to the roots

when you want to pull out the weeds;

a surgeon who knows that it won’t do just to operate on the fractures,

but that you have to lay bare the trauma inside;

a man who can look life and death in the eye,

not because he is more courageous than we are,

but because he lets himself get carried

by all of those for whom he does it.

And because James Nachtwey is all of these things,

and because he has never stopped believing

that there is reason behind his work,

because he has never stopped believing

that his images have their greatest possible effect

only if the attitude behind them

is an unfailing faith in humanity

and its ability for compassion…

for all of these reasons and many more

we should stop calling him a “war photographer”.

Instead, look upon him as a man of peace,

a man whose longing for peace

makes him go to war and expose himself…

in order to make peace.

He hates war with a passion,

and loves mankind with even more of a passion.

I can’t think of anyone who would deserve this award,

in this city of Dresden

more than James Nachtwey.