The latest work by Denis Piel, Down to Earth, currently on view in London, is in many ways an exploration of myths of origin, ranging across classical mythology and late 19th, early 20th century, Western art history.

In 2001, the French photographer witnessed the violent destruction of the World Trade Center, where is office was then located. The following year, Piel, his wife and son embarked for the South West of France, to take up residence at Château de Padiès, a 12th century renaissance château which they had been restoring since 1992; it is their home and the location of Les Jardins du Château de Padiès. The move to Lempaut the village where the castle is located, was a retreat from their world, which had violently lost its innocence.

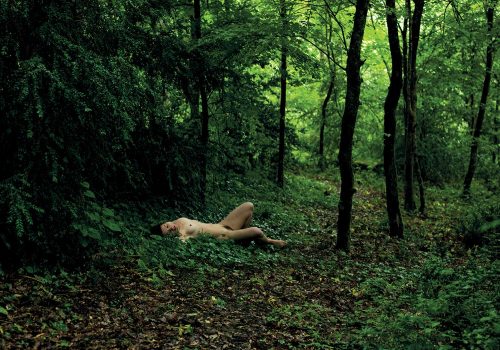

The collection of 38 images in Down to Earth were produced over the course of a year in the château and gardens. The title of the work suggests a lack of pretension, an essential “realism”; it suggests falling, and a notion of something unworldly returning to the world. Alongside images of the natural world; cultivated farmland, woods, harvest produce, male and female bodies at rest and at work, certain images also resonate directly with Western art history. White cotton sheets drying on a hedge seem to abstractly suggest Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde, a female nude standing in a field of sunflowers suggests Klimt’s painting of 1907, The Sunflower. A dove flying from a reclining nude resonates with the myth of Danaē, and of Leda, a spiritual and physical world, marrying.

The images exist almost as daydreams of the château, the house projects the dream, mapping out a liminal space of thresholds and becomings, populated by nymph-like and satyr-like nudes, sometimes in Bacchanalian reverie, sometimes engaged in agricultural work. There is a pulse within the images, a tide, like a breath, which animates. The exhibition begins with Growth at Sunrise, a series of images of the same scene taken at dawn over the course of a year, presented as a series of twelve images. It is a cycle. Complete. A calendar. A rhythmic pulse, which returns to the beginning, and continues the cycle again.

That sense of inhalation and exhalation, of expansion and retraction is found in images of the dormant earth and its later explosion into life. The images lead us through seasons. The majority of images are shot in black and white and demonstrate a rich vocabulary of texture and form, but as we enter the Bacchanal, high summer through to harvest, we are presented with richly saturated color images. Jewels. Berries. Fruit. As the earth and the environ begins to strain with the latent weight of its fecundity and fruit, a kind of intoxication begins to imbue the images, a Bacchanalian headiness in which the body becomes hyper-receptive to the sensuality of the physical world.

The imagery returns largely to black and white as the exuberant bloom of summer life begins to fade, and the nymphs and satyrs have retreated. An inky black sunflower head looms ominously like an accidental inkblot; an abstract swirl of hay could be a flimsy nest, or an obliterating swirl of scribbles. The life force of the earth is retreating beneath ground, beauty is still found in the fragile skeletons of what was once beautiful, but something uneasy has entered the space.

The final image in the exhibition shows an animal carcass, which has been butchered, laid out upon a table. The image is shocking in its beauty. A color image rich in shadows. Here is an image to contrast with the soft Romanticism of the nymph’s body, here is life stripped bare, here is matter stripped of the animating breath of the gods. Both alluring and horrifying, this is life transformed with the potential to nourish further life. There is a loss of innocence in the image, we get to see what lies beneath, the mystery of life has been deconstructed.

And then we are asked to begin the cycle of the exhibition again, to take another journey through the “year”. We are asked to forget and to deepen in equal measure. When we look at the image of the dove, we hold in mind also the jewel red image of the animal carcass. When we look at the heady images of the Bacchanal, we know that ahead lurks the black sunflower head which seems to herald death. And in the dormant winter images, we know eventually that even that world of black and white will blossom and bloom, delicate wiry shoots will poke through black plastic, fingers will gouge through earth seeking a place for life, soft sheets of leaf and petal will unfurl and transform this world.

Alongside the images from Down to Earth, the exhibition also presents Everyday Reality, a series of portraits of workers who have contributed to the maintenance and production of Les Jardins du Château de Padiès through the WWOOF organisation. These portraits are both an aspect of Down to Earth stripped bare, yet also the animating breath of the project. At some point within this space the workers from the garden merge with the statues of the dreaming château, and as the two worlds co-exist and overlap we glimpse the origins of Down to Earth.

Ruth MacPherson

Ruth MacPherson is an author specializing in arts, she has been living and working between the Highlands of Scotland and the South of France exploring ideas of journey, return, language and place.

Denis Piel, Down to Earth

Feb 5-16, 2018

Phillips

30 Berkeley Square, Mayfair

London W1J 6EX

United Kingdom