Deborah Bell Photographs presents Louis Faurer / Helen Levitt: New York City, 1938-1988 until April 19, 2025.

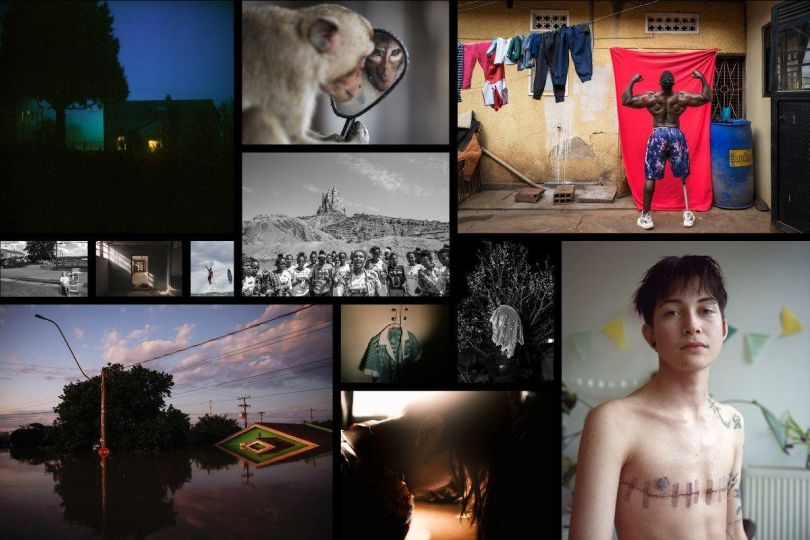

Levitt and Faurer were known to have admired and respected each other’s work greatly. Although both photographers came of age during a period when photography was lauded as a documentary tool for social change, neither used their camera with the aim of engaging in social criticism. The everyday life of encounters and exchanges among ordinary people are witnessed in Levitt’s witty images of children’s antics and their precocious chalk drawings. Faurer’s tender, gritty images of night wanderers in Times Square and layered, abstract cityscapes convey his fascination with the allure of mid-century New York City. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibited and acquired the work of both photographers early in their careers. In 1940, Levitt’s photographs were included in the museum’s inaugural exhibition of the newly formed Department of Photography (under the direction of Beaumont Newhall). Helen Levitt: Photographs of Children, organized by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, followed in 1943. Faurer’s work was first shown at MoMA in 1948 in the group exhibition organized by Edward Steichen, In and Out of Focus, which also included Levitt’s photographs.

Helen Levitt (1913-2009) was born in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. She became interested in photography in 1931 and received her technical training by working for a portrait photographer. By the age of 16, she had already resolved to become a professional photographer. In the early 1930s Levitt moved to the Yorkville section of Manhattan. Influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans, who became her friends, she bought a 35mm camera and began photographing on the streets of New York in the late 1930s. In 1937 she taught briefly in East Harlem under the Federal Art Project. By the late 1930s, her photographs began appearing in magazines such as Fortune, U.S. Camera, Minicam, and PM. Levitt is also lauded for her film projects, which she began in 1947. She collaborated with James Agee and Janice Loeb on the award-winning documentaries In the Street (1948 and 1952) and The Quiet One (1948). Levitt received a Ford Foundation Fellowship for filmmaking in 1964. In the late 1940s, Agee and Levitt began to collaborate on a book of her photographs, A Way of Seeing, for which Agee wrote the essay. It was eventually published in 1965, 10 years after Agee’s death. As the curator Susan Kismaric noted in the catalogue essay for her 1981 exhibition, American Children, at The Museum of Modern Art, Helen Levitt’s pictures were among the first in this country in the genre that would later be labelled “street photography.” John Szarkowski, MoMA’s head of the Department of Photographs from 1962-1991, eloquently explained the magic of Levitt’s photographs from the early 1940s: These pictures, quickly recognized as extraordinary, established a new documentary genre for American photography. … Levitt’s pictures report no unusual happenings; most of them show games of children, the errands and conversations of the middle-aged, and the observant waiting of the old. What is remarkable about the photographs is that these immemorially routine acts of life, practiced everywhere and always, are revealed as being full of grace, drama, humor, pathos, and surprise, and also that they are filled with the qualities of art, as though the street were a stage, and its people were all actors and actresses, mimes, orators, and dancers.

A native of Philadelphia, Louis Faurer (1916-2001) graduated from the South Philadelphia High School for Boys in 1934, after which he spent the next three summers sketching caricatures on the Boardwalk in Atlantic City. In 1937 his high school friend, the photographer Ben Somoroff, introduced him to photography. Faurer then started to photograph regularly on Market Street in Philadelphia. In 1946 Faurer began commuting between Philadelphia and New York, where he assisted the photographer Ben Rose in the New York studio Rose shared with another Philadelphian, the photographer Arnold Newman. Inspired by Walker Evans’ 1938 exhibition American Photographs at The Museum of Modern Art, its accompanying catalogue became Faurer’s bible. As the curator Anne Tucker observed in the catalogue essay for her superb and comprehensive retrospective of Faurer’s work at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Faurer assimilated the emotional sympathy that the FSA photographers evoked for their subjects, but he never embraced the idea of using his pictures to campaign against social ills or to advocate social change. Tucker describes Faurer as the master of city spaces: empty streets, overlapping signs, and the illogical spaces created by reflections. The energy of his pictures is found at interfaces, such as the space between approaching figures, the collision of sidewalks, and the simultaneously perceived inside and outside of a bus or a store. In 1947, Faurer met Robert Frank, who had just arrived in New York from Switzerland, in the offices of Harper’s Bazaar. Curator Susan Kismaric aptly describes their lifelong artistic bond: The anti-establishment ethos shared by Faurer and Frank became an integral part of their friendship. … Faurer was developing a 35mm aesthetic that described something of the darker side of the post-war American boom before Frank had completely developed his own. … Faurer was carving out a way of working that continued one of the oldest traditions in photography, pictures of strangers made on the streets of cities, yet he was injecting it with an intimacy that had not previously been captured, by anyone. In the same period, Winogrand, Friedlander, and others were developing their 35mm aesthetic…. The qualities of “film noir” of the 1940s and 1950s are also recognized as strong components of Faurer’s work. As the curator Lisa Hostetler explains, Stylistically, both [film noir and Faurer’s work] are characterized by an extensive use of shadow and darkness, a preference for unusual compositional techniques and oblique viewpoints, and a high-contrast, graphic sensibility. During the 1950s and 1960s, Faurer made his living by working on assignment, mainly for the editorial pages of LIFE and for fashion magazines such as Junior Bazaar, Harper’s Bazaar, Charm, Vogue, and Flair. During this period the only gallery dedicated to exhibiting photography was Helen Gee’s Limelight Gallery (1954-1960); instead, magazines were the creative forum for photography, as well as showcases for great literature, art, and theatre. Faurer often declared, “If you were published in those magazines, you were really an artist.” Faurer wrote in 1979 about his career: 1946 to 1951 were important years. I photographed almost daily and the hypnotic dusk light led me to Times Square. Several nights of photographing in that area and developing and printing in Robert Frank’s dark room became a way of life. … I was represented in Edward Steichen’s IN AND OUT OF FOCUS exhibit. In 1969, I needed new places, new faces and change. I tried Europe. I returned in the midseventies and was overwhelmed by the change that had occurred here. I took to photographing the new New York with an enthusiasm almost equal to the beginning…and, as an unexpected bonus, the photographer had become an artist! Faurer’s embrace in the late 1970s by the new frontier of photography galleries and collectors was mainly due to the legendary curator Walter Hopps, via the painter and actress Susan Hoffmann (later known as Viva). Hopps related in his 1979 essay, CONCERNING LOUIS FAURER: …with shocking suddenness in 1976 I came to believe that American photography of the moment belonged to Louis Faurer. What occurred for me in 1976 was the wholly unexpected opportunity to see all at once the existing body of Faurer’s work… This viewing arose from the bizarre, chance encounter in New York of the photographer William Eggleston and the actress and writer known as Viva. … The keen interest of Eggleston, seeing Faurer’s work for the first time as introduced by Viva, and their immediate efforts to interest others, proved crucial in reintroducing Faurer to public and professional view. … I was surprised to recognize images (but not Faurer’s name) which I had seen in an issue of Flair (a short-lived, opulent magazine from Cowles Publications). The photographs in that issue, which I acquired in 1950, immediately affected my thought about photography. … New York City has been the major center of Faurer’s work, and that city’s life at mid-century, his great subject. The city is totally Faurer’s natural habitat. … I am in awe of the high point he can reach in a photograph such as Family, Times Square, at the center of New York in the center of our century. Perhaps no other American image stands comparison with Picasso’s Family of Saltimbanques, on their imagined European plane in 1905. However little known or historically acknowledged, Faurer stands and lives as a master of his medium.

Louis Faurer / Helen Levitt : New York City, 1938-1988

Until April 19, 2025

Deborah Bell Photographs

526 West 26th Street, Room 411

New York, NY 10001

212-249-9400

www.deborahbellphotographs.com

Gallery hours: Thursday-Saturday, 11-5