What would the architecture of an actual museum of industrial machinery be like? Could machines continue to work as machines and still be part of such a museum? Or do they have to give up their operative life in order to become objects in a museum? To put it in more general terms, in what sense are museum pieces alive or dead? Or how could objects in a museum be made to come alive, and remain alive? What sort of ‘life’ would that be? And who would operate and embody this enlivening principle: the makers or users of the objects, the curator of the museum, or the viewer?

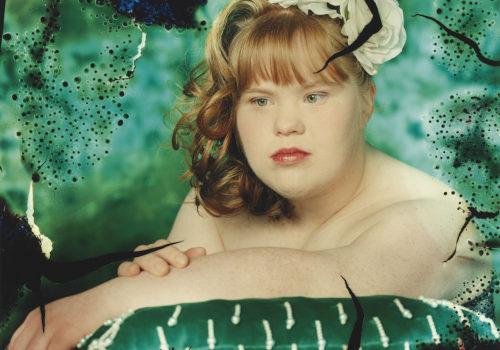

Dayanita Singh’s Museum of Machines makes a monument out of these doubts and questions, at once ironic and imbued with unexpected human feeling. Two great traditions of modern photography open out behind this body of work: the typological photography of the Bechers in Germany, and the industrial photography that became part of a public visual language of industry, commerce and national sentiment in India after the country became an independent nation in 1947. Yet, with her characteristic mischief, eye for fiction, and an unsettling habit of informing an image with wordless emotion when one is led to expect objectivity, Singh makes these photographic traditions stand on their heads – or even lose their heads – in her Museum of Machines.

The character of the typological grid, as inherited by the Bechers, is founded, on the one hand, on the absence of the human figure or any other accident of life inside the frame of each image. The Bechers called their towers, tanks, furnaces, ovens and other structures “anonymous sculptures” – anonymous, not only because we do not know who made or designed these sculptures, but also because they are so devoid of any human, or humane, identity. On the other hand, that way we are made to ponder them within the larger grid of images it encourages us to notice individual differences within the uniformity of each ‘type’. We are compelled to scrutinize industrial structures and objects as if we were studying human faces and forms, looking out as much for what makes each piece an individual as for what constitutes the type.

If we stand back and look at the entire grid, we see uniformity and repetition. But if we move closer and look at each piece in the grid, we begin to notice variation and difference. This takes us back to the origins of Western typology in the ‘human’ sciences of anthropology, physiognomy, criminology and, later, especially in Germany, genetics (at its most sinister). So, as we contemplate a water tower or blast furnace, and our own horizontality confronts the deadpan frontality of the photographed object, what we experience is a peculiar combination of the anthropomorphic and the impersonal, of the non-human (even the inhuman) animated by a human gaze, even if this human interest is only negatively invoked by the complete absence of human figures in the individual frames.

However, in Singh’s Museum Bhavan, as it was laid out at the Kiran Nadar Museum in Delhi in 2016, viewers came to the Museum of Machines after the Museum of Little Ladies, the Museum of Men and the Museum of Furniture. By that time, the eye was already tuned to the details and nuances of faces and bodies, of expressions, gestures and postures, and to the theatre of human beings cohabiting with objects of different kinds in spaces whose emptiness often resonates with presence. So, when we came to the Museum of Machines, the eye for the fineness of human particularity experienced a sudden expansion of scale, and a shift of context from the domestic to the gigantic, from the intimate to the industrial. But the physical size of the museum structure and of the images remained the same, demanding the same closeness of viewing. So, the machines, encountered singly or in groups, confronted us as presences that are monstrously human, but the monstrosity of scale was enlivened and transfigured by the photographer’s abiding interest in human states of being, feeling and relationships.

We do not know, and cannot figure out most often, what these machines make. So, we are freed from functionality to contemplate, instead, who these machines are, and what sort of creature, or character, they might be turned into in our imagination (or in their own). Even when our imagination is not made to work in this anthropomorphic way, a machine might create the setting for a situation or scene, a human story, the details or atmosphere of which would lie as much in their withholding of documentary information in a sort of unpeopled bareness as in a wealth of finely captured texture, form or tone. There are hints of human presence here and there, and sometimes, in the midst of scenes of what could have been the modern industrial sublime, we find evidence of basic human hunger and thirst, curiosity and conversation – empty glasses, bottles and tiffin-carriers lying around, or an elderly gentleman of patrician mildness standing graciously in his spectacles and shirt-sleeves to welcome the viewer into a neon-and- steel castle of mysterious giants.

As we spend more time with these creatures and contemplate the spaces of encounter they inhabit or conjure up, what begins to rise up within us is, paradoxically, a sense of personality and personhood. There is, first, our own personhood as we confront, as viewers, these tangible and intangible presences in all their unfleshly, larger-than-life singularity. Second, there is the personality of another absent creature: the photographer and museum-keeper. This person’s quietly obsessive preoccupation with recording and preserving these forms and structures becomes the thread of feeling, of thought and of something else – something unique and irresistible that cannot be put in words – that brings together all these diverse objects and spaces to create a single universe of strange, but immediately recognizable, beings.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, even as it compels us to wonder why, Singh chose to turn this particular museum, her Museum of Machines, into a “confession chamber” in Delhi, for the actual use of which visitors would have to make an appointment with her as the keeper of her own museums. As a confession chamber, the arms of the museum were folded in to create a polygonal tower-like enclosure, inside which was a dark and narrow space with a single wooden stool. Viewers had to squeeze into this space, one at a time, and sit inside the museum’s claustrophobic embrace – like Shakespeare’s Ariel forced back into the “cloven pine” from which he had been freed by Prospero – to commune in solitude with the memory of a machine of their choice.

Aveek Sen

A curator and writer on art, literature, music and society, Aveek Sen is also a Senior Assistant Editor, The Telegraph, Kolkata. Sen’s curatorial practice has a focus on photography and has received the Infinity Award for Writing on Photography in 2009.

Dayanita Singh, Museum of Machines

October 12, 2016 to January 8, 2017

Mast Gallery

Via Speranza, 42

40133 Bologna

Italy

http://www.mast.org/