In one of his early series, Barriers, David Zimmerman began a reflection on boundaries and the way humans scar the landscape while imposing themselves upon it. Later on, Salton Seas explored the paradoxes of a place that is both paradise and toxic dump, filled with the haunting shapes of pelican skeletons as well as half-destroyed buildings and boats that the waters try to reclaim.

After the disastrous sinking of a British Petroleum oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, Zimmerman posed spill laborers,fishermen and charter captains in makeshift studios. Their faces are ones that usually go unseen in the tragedy, having been dispossesed from both their livelihood and their environment. This may be when Zimmerman realized that the story of people often echoes the story of the territory.

The New Mexico desert is not an overwhelming landscape such as the Rockies or the Grand Canyon, but it possesses a quiet magic that suits Zimmerman’s contemplative personality. He describes the subtle effect of the desert as “more like a whisper.” In Deserts Zimmerman documented extreme conditions in light and climate as well as the wreckage, racket and pollution brought about by off-track desert racing.

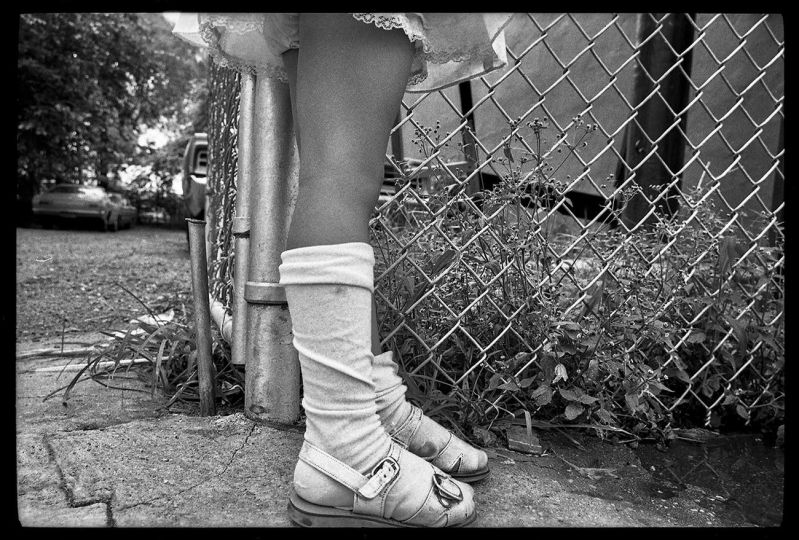

Pursuing his work in the desert, for several months he shared the homes of families who exist at the fringes of society. Among their houses he discovered piles of discarded clothing beaten flat by wind, cold and heat, used by settlers as insulation on their shelters’ roofs. These became the subject of his series Last Refuge.

In the small and the up-close, he found the same beautiful curves and faded colors as the infinite vistas of the desert dunes. Blues, greens and browns, scraps of wool, nylon and cotton, stained and frayed, rusted zippers and broken buttons, fill the frame to capacity like geological strata. Zimmerman’s beautiful large prints give an almost sculptural sense of texture and depth, reminding us of Antonio Recalcati’s direct body imprints and Domenico Gnoli’s paintings of tapestries, jackets or bedspreads, thickened with sand and plaster. It is not surprising that before he became a photographer Zimmerman was a painter and sculptor.

A man lives beneath the clothes but never appears. The clothing is draped against his absence and it is an absence that fills these haunting images with beauty and melancholy. They seem to have retained the contours of the bodies they once clad and speak of us about memory and loss. They are archeological remains of a sort. Like the desert, the layers of clothing , a small territory, are “altered or impacted landscapes.”

When the fragile roof of their shelter collapses, the inhabitants just move to a new location, leaving it behind. The sculptural piles of clothing remain as testimonies of their absence.

Even though they speak to us of an endangered territory and its marginalized inhabitants, Zimmerman’s photographs leave us room for hope. They do not illustrate an idea but remain open to mystery, projecting a metaphysical presence.

Since the 1970s a number of photographers have worked on the theme of the endangered environment and the newly vulnerable territory, some of them seeking an ironic counterpoint to the idealized images of the desert popularized by the generation of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. The desert has often been their preferred subject, maybe because on such a background the scars of man’s intervention can be so cruelly visible.

But David Zimmerman’s work is unique in that it is positioned at the crossroads of two traditions: landscape photography and the study of the impact of man on his environment, represented by photographers such as Robert Adams and Richard Misrach, both of whom he admires; and humanistic photography in the tradition of the Farm Security Administration, which documented the great migrations in the wake of the Depression. Whether indirectly, through photos of the territory, or directly, through portraits, it is always people who are at the center of Zimmerman’s preoccupations.

Between sand and sky, earth and heaven, the images of Last Refuge are above all a testimony to man’s resilience and spirit, living in a damaged territory.

Carole Naggar with the courtesy of Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

Carole Naggar, photography historian, co-founder with her husband Fred Ritchin and Special Projects Editor of Pixelpress.

David Zimmerman, Last Refuge

Until January 28th 2012

Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

560 Broadway Suite 205

New York NY 10012

T. 212 966 0796