For the past forty years, David Strick has studied the mysterious phenomenon that is Hollywood, examining its artificiality and its affect on the world beyond the city limits. Strick has just started a blog where he combines the media’s image of Hollywood with his own in order to give an insider’s view of the industry. A portrait of the photographer in ten points.

David Strick’s background

Strick’s great aunt Gale Sondergaard won the very first Academy Award ever given in the Best Supporting Actress category in 1936 for the movie Anthony Adverse, directed by Mervyn LeRoy. She made about 40-45 movies in all with major producers, and her husband was a New York theater director who became a movie director here in Los Angeles, Herbert Biberman. Hebert served six months in prison for his refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee

during the McCarthy era and both him and his wife were blacklisted for over 20 years. In the next generation, his parents had been CP members – his father, Joseph Strick, was actually kicked out of the party in the early 50’s, and his mother quit. His father broke into the movies by making a film called The Savage Eye (1959), on week-ends, with friends like Haskell Wexler. He notably directed an adaptation of Ulysses by James Joyce in 1967: “As a group, they were too young a generation to have notable Hollywood careers when the politics first got ugly so they were below the radar of the blacklist and could barely find work in Hollywood at that time. My father was what would now be called a maverick film director.” It doesn’t stop here: David Strick’s mother started somewhere in the 70’s-80’s and became a film publicist. His wife has been a film executive, in the 1990’s mostly. His distant cousin was a movie actor and TV director named Abner Biberman, and he surely has a relative who played violin in a B movie !

“This Hollywood background is independent from my focus on the phenomenology of it. I am a still photographer, not a filmmaker. I was influenced by my relatives work and stories, but I didn’t want to follow their path. I very much wanted something of my own”, Strick comments.

His childhood memory

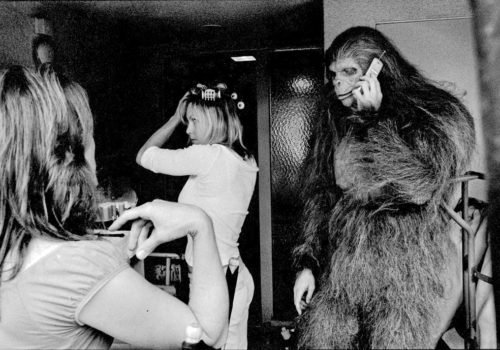

“I remember being on the set of the movie The Balcony, based on a Jean Genet play.

There was a bordelo scene in which the judge wanted to be humiliated by a dominatrix while dressed up with a wig and be disciplined the way he disciplines criminals at court. I remember being on the set and noticing people wearing these outrageous costumes. That was my first brief exposure to this kind of industrial surrealism. The way I processed that was as a kind of curiosity about the strangeness of everything. Being an adult seemed to be a very serious form of play acting.”

His definition of movie making

“It’s like fishing: long periods of boredom interrupted by brief periods of cruelty to animals. Movie making is a lot like that. It’s a lot of waiting and repetition. It’s a lot of standing around doing nothing and then suddenly there is something to shoot.”

Strick and the camera

“When I am not shooting, I am not shooting. I rarely have the urge to shoot simply to be photographically active. When I am off, I am off ! But on the other hand, I get weirdly mono-focused when I shoot. It is almost inhuman, I become this camera extension, in a Christopher Isherwood sense.”

His favorite pics

“I have probably 150 pictures that are my favorite, and then maybe hundreds more that could work in a mix and add to the total as a variation. Recently, I got tired of pondering all the editorial choices it’s possible to make when editing your own photos and I key-worded all my pictures. Then, I thought: “Let me choose an arbitrary category from among the keywords, something ridiculous that people would not necessarily anticipate or have any particular reason to care about”, and I chose “pointing”. The result was hilarious. There was a subconscious mechanism in my brain triggered by the pointing and the results were no worse than anything else.”

His Hollywood most hated and loved picture

“On a set of a movie called Deep Impact – an “asteroid hits the Earth” movie – the picture I got was of an elephant taking a dump.The publicist was first really upset but then she called the next day saying: “Your picture has gone from being the most hated photograph in the history of Paramount Studios to being one of the best liked in one day. The producer and the director both want prints”.”

His wished picture

“I have strange dreams of pictures I haven’t yet made, but I have to wait for actuality to present itself to me.”

His humor

“What I am examining is entertainment, so the depiction of it should be entertaining also. If you can’t, you are in the wrong business. But humor is not just a reflex. Hollywood is a world with its own sort of consequentiality. It is like a Potemkin village, but even a Potemkin village has meaning. Sex is an example – Sex on set is a bunch of arms and legs and people being bored on the sideline. It’s both funny but meaningful and insanely human. Visual humour is an incredible way to reveal contradiction, but it is also an intense discipline: everything has to be dramatically correct within a frame, just as it does when telling a joke. Humorists I care about the most are social humorists, Richard Pryor, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce.”

His various set of excuses and styles

“I used to shoot Hollywood only in black & white, reasoning that eliminating color stripped away the false surfaces of things. Then after a while, Premiere Magazine told me I had to shoot for them in color and I really liked the results, so my theory became that surfaces were important after all, that color showed the drama and artificiality of entertainment culture even more clearly than black & white, which is itself an artificiality. Now I try to justify the combination of the two by referencing the Nouvelle Vague movies of the early 60’s. I switched from one set of excuses to another to justify my choice of practice, because I learned that theory follows practice more reliably than practice follows theory. I don’t know if that makes me a wise man or a liar.

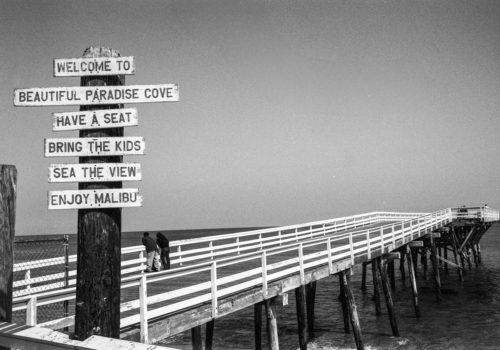

I had a sense that I could understand the center by photographing the periphery, seeing the dreams and yearning of people on the sidelines reflecting what they think lies at the center, the absurdities of the streets contrasting with the glamorousness of the surroundings. I was very influenced by Nathanael West’s analytical view of Hollywood in his “The Day of the Locust”, published in 1939 – a book about Hollywood losers that ends in a huge riot”.

Strick’s project for the future

“I haven’t done another book since Our Hollywood so it’s probably about time to look at what I have.”