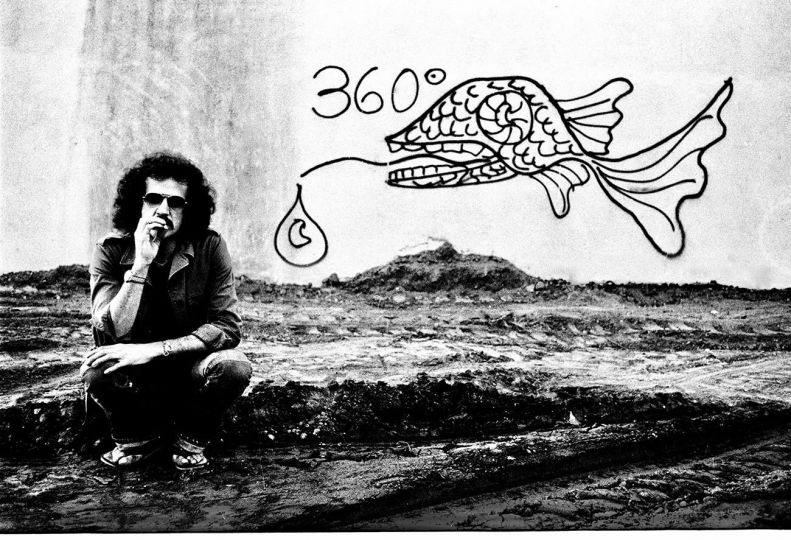

One of the most venerated figures in photography worldwide, David Goldblatt has documented South Africa’s complex contemporary history over seventy years. His internationally acclaimed work constitutes an invaluable archive on the inner workings and structural violence of the apartheid regime, which was in full force between 1948 and 1991.

Inhabiting the Silence presents several bodies of work and iconic images, as well as those lesser known, offering intimate insight into what was the “banality of evil” during decades of racial segregation.

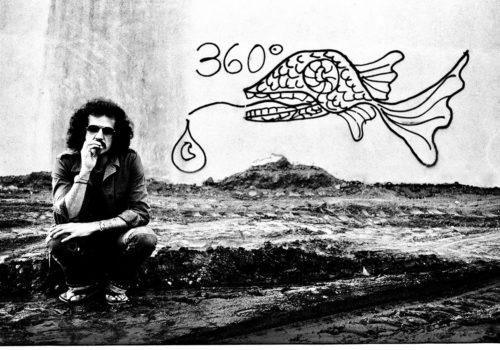

The son of Jewish Lithuanian parents who settled in South Africa to escape persecution, David Goldblatt was seventeen years old when apartheid was formalised. The trajectory of his family history echoed the violence and injustice of such an oppressive system. Although his hostility towards the racist regime was evident, his ethical exigence required that he assume a distanced standpoint. At the risk of being misunderstood at times, this critical observer of South African society chose to refrain from becoming involved with collectives and political movements against apartheid. He took spectacular images and never conformed to whistle-blower photojournalism conventions.

The power of David Goldblatt’s work resides in the need for every image to expose reality in its complexity, but also in its obscurity and impetuousness. His documentary approach can be linked to that of Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans as he revealed the most invisible and silenced layers of a fractured South African society. As much of his work displayed potent political regard, his point of view remained indirect and implicit. David Goldblatt captured ordinary moments in life and produced images that continue to bear the weight of history as seen in portraits of township residents removed from their homes, those of workers constrained to gruelling public transportation, or even pictures of miners in the shafts of a Dantean hell. For Goldblatt, the root of evil also penetrates ruins, urban and industrial architecture, roads, buildings and houses which he photographed tirelessly. He was interested in structures because he would say “they tell the necessities, preferences, imperatives and values of those who constructed and used them. For David Goldblatt, every image was an inextricably thoughtful act and gesture of resistance zooming in on the abjection and inhumanity of racialising public space, the deprivation of all freedoms for people of colour, forced migration and brutal expropriation. As his friend and writer Nadine Gordimer wrote “his photographs have an unspoken political meaning that goes beyond the obvious images – they reveal incessant violence against human beings in the continuity of everyday life”.

Goldblatt’s work suggests the founding of a type of visual grammar which leaves room to interrogate his “silent” images. Abstentious, evocative, meticulous in their technical development, his photographs were predominantly in black and white during apartheid for colour seemed to soft to represent the harsh reality during this dark period of the nation’s collective history.

In his rigorous visual chronicles of ‘a segregated world’, Goldblatt used words, legends or lenghthy and detailed text which is connected with each photograph. For the artist, these texts are as important as the work itself.

Soaring in the suspended time of photography and shedding light on the heart of the unjustifiable system of aparthed, David Goldblatt’s practice portays the human in the inhuman landscape.

Marie-Ann Yemsi, Guest Curator