“If we and our dogs are healthy, and we and they do not get run over or destroyed in the recklessness of our youth, seven is the number of companions we are allowed in our lifetime,” Danny Lyon explains in the beginning of his new book, The Seventh Dog (Phaidon). He continues, “This book is a record of my life. I have decided to start at the end of my life, and proceed backwards, so that we can begin in the present and go back to the past. In the beginning I had my dreams, but no way of knowing what awaited me. Now I can look back with satisfaction, knowing that, for me anyway., most things came out more or less as they were meant to be.”

Life is predetermined in retrospect, I believe. Choice is an illusion, albeit one of the most marvelous kind, for it allows us to believe that we have a hand in shaping our destiny. But things were only ever going to be exactly as they were, for if it were to have gone another way, that would be so. As we move along our path, we learn ourselves, and the better we understand our conscious and unconscious motivations, the shorter the period of retrospect. It becomes so that one may reach the absolute ideal, of being so incredibly present in the moment that the hows and why of it all are not questions but answers upon which we act, clear, with direct awareness of the reality we intend to manifest.

Artists, perhaps more so than other folk, are people who live in the space where the unconscious and conscious mind intersect. They are ceaselessly searching for an understanding of life, and using their talents to communicate their questions and their findings. Those who do it best are those who are consistent over an intense or extensive period of time, so that we may reflect on their journey, and the way in which their path lead them to the present time.

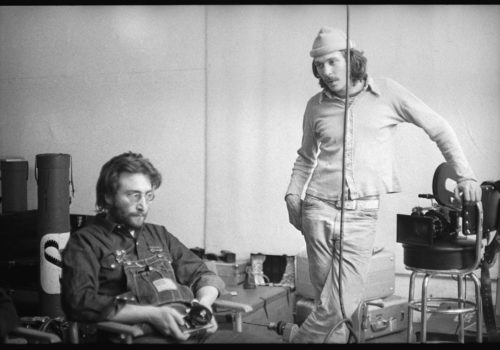

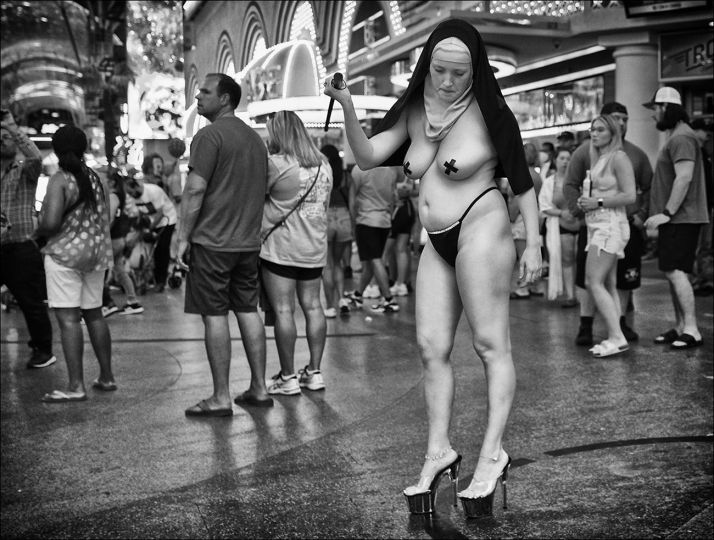

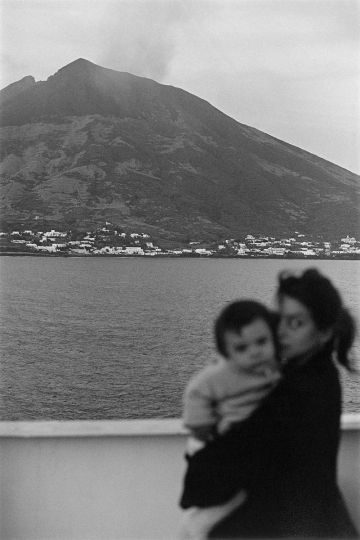

Danny Lyon is one of the most intriguing contemporary photographers for his ceaseless inquiry into some of the most challenging questions of our time. His understanding of humanity is based in a respect for life, which allow him to explore the dark corners of existence with bright and sharp eyes. The Seventh Dog is more than just a career retrospective; it reads as an autobiography, a memoir of Lyon’s travels on earth in search of answers to questions most fear to ask.

The book begins with the Occupy movement, and goes all the way back to Lyon asking the hardest question of all, “What was I looking for?” A portrait of the artist is always his or her subject, and so it may be that Lyon was looking for an understanding of himself in relation to the times in which he lived. For it is the subject of his photographs that consistently overwhelms with an energy that can only be known by one who possesses it themselves.

Lyon’s edit of his work reveals another side of his personal history, in a series of correspondence that he kept throughout the years. Letters to and from those whom he met along the way, a series of ideas that transfer from the images he created into the words he shared. The result is two different systems of symbolic thought, each informing the other with nuances and details that can only be perceived in their literal form.

Lyon writes a letter on February 12, 1964, to his parents, which appears in the chapter on his documentation of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1964-1962, in which he states, “In many ways I think that the things I do here are good for me to use a poor term. I have a responsibility in my work here, which frankly I hate. Somehow, because of the movement and the conditions of the country I feel forced to face that responsibility. In the particular form it means doing SNCC pamphlets instead of riding and photographing motorcycles. I am very aware that the lure of New York is the lure of fun and irresponsibility. To just do things that are fun for the cause means very little to one’s self. In general I seem to believe that to leave SNCC would be to turn away from the movement.”

By including his letter, Lyon provides us with an intimate understanding of his psyche at this time, an understanding that might be felt but not necessarily verbalized when looking at his work. That is the beauty of the autobiographical work, the setting of the record as it was lived, as it was remembered, as it speaks to the past, present, and future with every turn of the page.

And so it is, that in a chapter titled, “New York, 2012” which appears at the front of the book, Lyon explains the importance of including his words along side his work. “Many years ago I was being driven along Central Park West in a New York taxi with Robert Frank. When I spoke of using texts with words with photography, as part of what were then called ‘photography books,’ Robert said, ‘Well, then that’s the end of it.’ The year was 1969, and it was not ‘the end of it.’ As a young photographer deep into a career of making picture books with texts, I couldn’t help but feel that Frank’s comment smacked of kicking out the ladder.”

We are fortunate that Lyon is an iconoclast, influenced only by his internal compass, that guides him to his truth, a truth that is as evident as it is universal. There will always be leaders, and there will always be followers. And those who make history are those who charted their own course. The Seventh Dog is a map of one man’s life, as much a document of American history as it is a memoir of a man whose work changed the course of photography and shaped the zeitgeist.

http://www.phaidon.com/store/photography/the-seventh-dog-9780714848532/

http://missrosen.wordpress.com