Copyright is a legal right created by the law of a country that grants the creator of an original work exclusive rights for its use and distribution. This is usually only for a limited time. The exclusive rights are not absolute but limited by limitations and exceptions to copyright law, including fair use. A major limitation on copyright is that copyright protects only the original expression of ideas, and not the underlying ideas themselves. In France in 1863, in the United States in 1883, in Italy in 1886, the court set precedent for photography to be legally included as a means of artistic and original expression.

The intellectual property rights on photographs are protected in different jurisdictions by the laws governing copyright and moral rights. In some cases photography may be restricted by civil or criminal law. Publishing certain photographs can be restricted by privacy or other laws. Photography of certain subject matter can be generally restricted in the interests of public morality and the protection of children.

Copyright can subsist in an original photograph, i.e. a recording of light or other radiation on any medium on which an image is produced or from which an image by any means be produced, and which is not part of a film. Whilst photographs are classified as artistic works, the subsistence of copyright does not depend on artistic merit. The owner of the copyright of a photograph is the photographer — the person who creates it, by default. However, where a photograph is taken by an employee in the course of employment, the first owner of the copyright is the employer, unless there is an agreement to the contrary — as usual.

Copyright which subsists in a photograph protects not merely the photographer from direct copying of his/her work, but also from indirect copying to reproduce his/her work, where a substantial part of his/her work has been copied.

Copyright in a photograph lasts for 70 years from the end of the year in which the photographer dies. A consequence of this lengthy period of existence of the copyright is that many family photographs which have no market value, but significant emotional value, remain subject to copyright, even when the original photographer cannot be traced (a problem known as copyright orphan), has given up photography, or died. In the absence of a licence, it will be an infringement of copyright of the photographs to copy them: Scanning old family photographs, without permission, to a digital file for personal use is prima facie an infringement of copyright.

Certain photographs may not be protected by copyright. Section 171(3) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 gives courts jurisdiction to refrain from enforcing the copyright which subsists in works on the grounds of public interest. For example, patent diagrams are held to be in the public domain, and are thus not subject to copyright.

Infringement of the copyright which subsists in a photograph can be performed through copying the photograph. This is because the owner of the copyright in the photograph has the exclusive right to copy the photograph. For there to be infringement of the copyright of a photograph, there must be copying of a substantial part of the photograph.

A photograph can also be a mechanism of infringement of the copyright which subsists in another work. For example, a photograph which copies a substantial part of an artistic work, such as a sculpture, painting or another photograph (without permission) would infringe the copyright which subsists in those works.

However, the subject matter of a photograph is not necessarily subject to an independent copyright. For example, in the Creation Records case, a photographer, attempting to create a photograph for an album cover, set up an elaborate and artificial scene. A photographer from a newspaper covertly photographed the scene and published it in the newspaper. The court held that the newspaper photographer did not infringe the official photographer’s copyright. Copyright did not subsist in the scene itself – it was too temporary to be a collage, and could not be categorised as any other form of artistic work.

The protection of photographs in this manner has been criticised on two grounds.

Firstly, it is argued that photographs should not be protected as artistic works, but should instead be protected in a manner similar to that of sound recordings and films. In other words, copyright should not protect the subject matter of a photograph as a matter of course as a consequence of a photograph being taken. It is argued that protection of photographs as artistic works is anomalous, in that photography is ultimately a medium of reproduction, rather than creation. As such, it is more similar to a film, or sound recording than a painting or sculpture. Some photographers share this view. For example, Michael Reichmann described photography as an art of disclosure, as opposed to an art of inclusion.

Secondly, it is argued that the protection of photographs as artistic works leads to bizarre results. Subject matter is protected irrespective of the artistic merit of a photograph. The subject matter of a photograph is protected even when it is not deserving of protection. For copyright to subsist in photographs as artistic works, the photographs must be original, since the English test for originality is based on skill, labour and judgment. That said, it is possible that the threshold of originality is very low.

It is possible to say with a high degree of confidence that photographs of three-dimensional objects, including artistic works, will be treated by a court as themselves original artistic works, and as such, will be subject to copyright. It is likely that a photograph (including a scan – digital scanning counts as photography for the purposes of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988) of a two dimensional artistic work, such as another photograph or a painting will also be subject to copyright if a significant amount of skill, labour and judgment went into its creation.

In the USA, Photographing accident scenes and law enforcement activities is usually legal. At the same time, one must not hinder the operations of law enforcement, medical, emergency, or security personnel by filming.

In Hong Kong, some public property owned by government, such as law courts, government buildings, libraries, civic centres and some of the museums in Hong Kong, photography is not allowed without permission from the government. It is illegal to equip or take photographs and recording in a place of public entertainment, such as cinemas and indoor theaters.

In Hungary, from 15 March 2014 when the long-awaited Civil Code was published, the law re-stated that a person had the right to refuse being photographed. However, implied consent exists: it is not illegal to photograph a person who does not actively object.

In Macau, a photographer must not take or publish any photographs of a person against his/her will without legal justification, even in a public place. Additionally, photography of police officers in Macau is illegal.

In Sudan and South Sudan, travelers who wish to take any photographs must obtain a photography permit from the Ministry of Interior, Department of Aliens.

In India, regulations apply to land-based photography for certain locations, and a permit is required for aerial photography, which normally takes over a month to be issued.

In Iceland, calling oneself a photographer, in line with most other trades in Iceland, requires the person to hold a Journeyman’s or Master’s Certificates in the industry. Exceptions can be made in low populated areas, or for people coming from within the EEA.

In Spain, taking pictures of police officers in many circumstances was made illegal by a 2015 “Citizens’ Security Law” with the stated purpose of protecting police officers and their families from harassment, the law have generated controversy because it may be harder to denounce police brutality.

In France, the maximum penalty for distributing violent images is three years in prison and a fine of up to €75,000. New laws need time for interpretation, French law considers the dissemination of violent images a potential incitement of terrorist activity, but probably doesn’t apply to all citizens, otherwise Nikki Haley, United States’ Ambassador United Nations, could enfrain French laws when showing violent pictures.

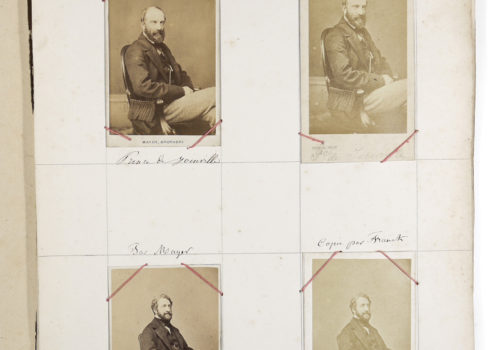

Serge Plantureux

Serge Plantureux is a French photography collector living in Paris, France.