This is the 39th dialogue of the Collezione Ettore Molinario. A dialogue that celebrates the 75th year of the publication of what I believe to be the most important Italian critical essay on photography, Message from the Darkroom, signed in 1949 by Carlo Mollino, the great architect. For me, an initiatory book. And not only to the mysteries of photography.

Ettore Molinario

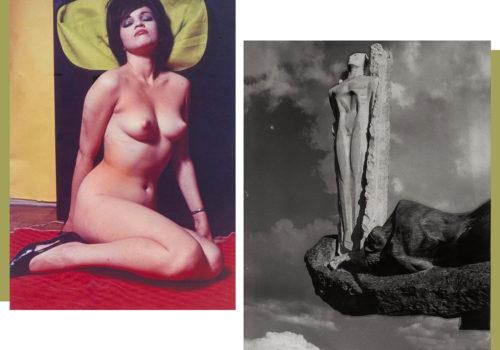

When I read it for the first time, and I had just started my collection, I realised I had met my mentor. It is easy to fall in love with Carlo Mollino, absolute genius. Less obvious is to follow him through the mysterious pages of his extraordinary volume Message from the Darkroom and make the authors cited by the great architect your own authors. Or even more, to assume Mollino’s gaze on photography and on the «fantasies of an impossible everyday life» as your own gaze. We think of Mollino and our thought goes instinctively to his famous nudes, and through a play of reflections and deep harmonies I believe he would have liked the body of a burlesque starlet like Victoria Williams, the domestic set that surprises her among paper backdrops, a carpet as red as her lips, her walking décolleté and the watch on her wrist, because when you are naked and you offer the splendour of your body to the world it is always important to know what time it is. Definitely a Mollinian woman, my Victoria. But strange to say, it is not that chapter of Mollino’s research that struck me the most. It is something else.

Which else means the entire course of his book, starting from the first chapter, A Short History of Taste in Photography and from the image chosen to illustrate it. For Mollino, «the oldest photograph in the world», dated 1826, is not the famous view from Nicéphore Niépce’s window, but his laid table. A still life for a single guest, a bowl, a bottle of wine, a piece of bread, a knife, a spoon on a white tablecloth. In front of the mystery of the camera, which Mollino calls «the black box suspected of too many gratuitous wonders», as in front of the creation of our double, we are alone. But maybe I didn’t want to be so alone so, like a skier in fresh snow, and Mollino was an acrobatic skier, I began to follow in his footsteps. I slipped into it starting from his woman-obsession who also became mine, the Countess of Castiglione. Mollino calls her princess and says of her: «Being a mannequin, no matter how beautiful, has never been her strong point». She wanted to be a «person», the Countess. Following the pages of Message from the Darkroom I searched for and found other Mollinian «people» such as Charles Baudelaire portrayed by Etienne Carjat, Julia Margaret Cameron, «nonchalantly Pre-Raphaelite», Atget, and I imagine the joy when he immersed himself, says Mollino, in a «forest of squalid objects», and then Edward Steichen, «who senses the limits and the rapid extinction in a closed circle of pictorial photography», and finally Man Ray, the «mad entomologist».

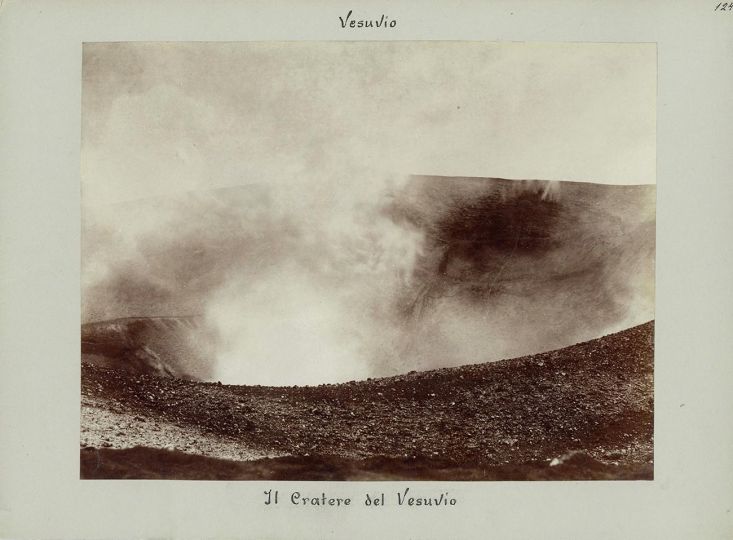

Speaking of Man Ray, Mollino speaks of himself. He writes: «The encounter with Man Ray takes place in the silence of the night or dawn, the fires of every will extinguished». The pinnacle are the famous rayograms, «phosphorescent larvae in the night of a negative». For Carlo Mollino, Man Ray’s secret was his «unprejudiced eclecticism». Eclecticism, an attitude of the soul that I love very much. And following the critical eclecticism of Mollino, who was architect, designer, photographer, skier, pilot of crazy speeds, I too have looked at astronomical photography, from the formation of stars to lunar craters, and I too would like a portrait of Cléo de Mérode among the ballerinas of the Opéra, and I too would feel the need in my collection for the frightening wonder of a «nucleus and protoplasm of a plant cell», magnified twelve hundred times. I would like everything that Mollino wanted and I also deeply feel his faith in photography, when on the last page of his writing, Mollino himself admitted to encountering «photographs, concrete poetry, even on fragile sheets, between one pulping and another of the ephemeral life of today’s paper». If it hadn’t been for his solitary gaze, for his sense of time passing and his attempt to stem it with the strength of those wonderful fragile sheets, I would never have chosen for my collection the image by Carlo Mollino that I love most of all, the collage of the Monumento ai caduti per la libertà. If there is something that helps us resist against every fragility, between one waste and another, it is our awareness of being alone.

Ettore Molinario

DISCOVER COLLECTION DIALOGUES

https://collezionemolinario.com/en/dialogues