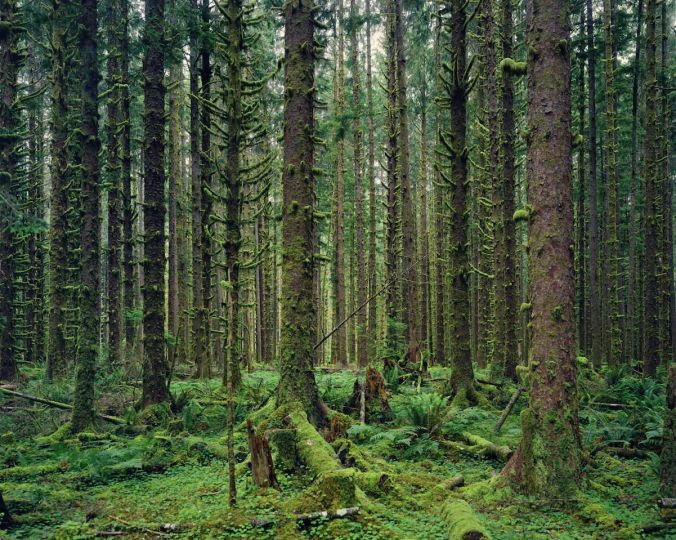

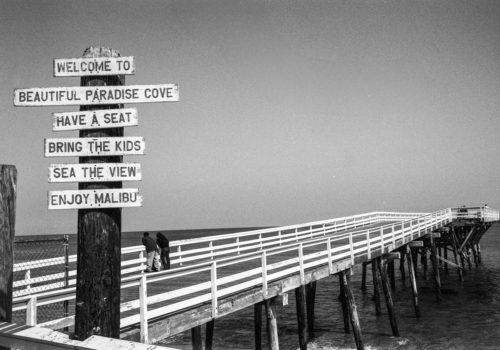

Michael Christopher Brown is an American photographer based in Los Angeles and raised in the Skagit Valley, a farming community in Washington State. His work in Cuba includes Paradiso, which explores the island’s electronic music scene and youth culture as well as Yo Soy Fidel , a book documenting the funeral procession of Fidel Castro.

His work in Libya, Libyan Sugar (2016), which received the ICP Infinity Award, explored ethical distance and the iconography of warfare. In Libyan Sugar, as in many of his projects, he uses a camera phone. His work from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congo Sunrise, will be published in 2020/2021 as one of a series of three books, which includes two books of collected work.

A contributing photographer to publications such as National Geographic Magazine and The New York Times Magazine, Brown was subject of the 2012 HBO documentary Witness: Libya. His photographs were exhibited at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Instituto Cervantes (New York), The Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), the Annenberg Space for Photography, and the Brooklyn Museum.

https://www.michaelchristopherbrown.com

Patricia Lanza : You have a large body of work on Cuba, how did this begin and over what time period?

Michael Christopher Brown : I first went to Cuba after Obama’s 2014 announcement of new relations between the US and Cuban governments. On assignment for The New York Times Magazine, I photographed mainly Old Havana to show what might change and be effected by the new relations. I stay there after the job for another month and returned to Cuba frequently during the following two years to continue photographing the lives of some Cuban DJ’s of Electronic Music and their friends.

PL : The Series, Paradiso, is an intimate portrait of Cuba’s Youth Culture. What were the challenges in photographing this community?

MCB : Mainly the language, I did not speak Spanish well enough to understand the Cuban dialect! Fortunately some of the youth knew some English, though generally not enough for conversation. I could have done more in the community had I known more of the language. But there were benefits to spending much of the time just observing as it opened the way to more photography, as many of the youth would just let me take pictures and continue what they were doing. But we connected through the music and the nightlife! Another challenge was earning the trust of some of the youth who did not fully trust what I was doing, so I focused on those who did and was lucky to have the friendship of Rene, one of the DJ’s respected within the community. When Rene began to trust me it opened the doors to others trust.

PL : Street series focusing on the street culture of two places: Havana and Pinar del Rio. How did you come to choose these?

MCB : These were the two areas of Cuba in which I spent much time, whether working or exploring and walking the streets on vacation. I had many images from these areas and just combined them into a series of observations.

PL : Yo Soy Fidel, is your book publication and homage to the death of Fidel Castro. Discuss how this came about from creating the images to the final book production. Did this have any effect on your view of Castro and his relationship to the Cuban people?

MCB : After spending two years working in Cuba and learning about Fidel and the history from the country’s youth, I felt like I knew much about Fidel though had never seen him. When he died, I was there on vacation and fortunately had already rented an SUV, which I used to travel up and down the highway during the Caravan which transported Fidel’s remains from Havana to Santiago. It was a surreal time, we were told there would be no access on the road but each day we tried and were able to attain access. When I initially heard of this, it reminded me of Paul Fusco’s Funeral Train though I knew as a photographer that I needed to approach it differently, which I did both aesthetically/photographically and in the book by utilizing handwriting in the first person. There were many people who came to see Fidel pass and to the rally’s, though it was said that most Cubans (as most Cubans work for the state) were told by the government to attend. So, it is tough to say if most were supporters or not, but there were definitely many supporters, especially while traveling east through the countryside areas and while approach Fidel’s home state of Santiago. Overall millions of Cubans came, if anything, to be a part of this massive moment in history.

PL : Did the closing of individual travel to Cuba from the USA have any effect on your ability to work there now and in the future?

MCB : Initially I traveled there through Canada, as there were no direct flights then from the United States. But Americans have been traveling to Cuba for ages, whether through Canada or Mexico or the Bahamas or Panama or wherever. The problem is not on the Cuban side, but on the American side, but it is easy to navigate as the Cuban’s did not stamp your passport if you were American. I have not been to Cuba in several years, with everything happening now in life (a mortgage, a baby, etc.!) but hope to be back soon.

PL : What are your future plans for work in Cuba? What are you working on now?

MCB : I have been working a bit in Los Angeles and on developing a series of Congo (DRC) books, which are requiring much work. Am also currently developing a Podcast that is loosely about storytelling. Still plan to return to Cuba but next time the focus will be more historically based.