Christian Houge is a Norwegian artist residing in Oslo. For over twenty years. the focus of his work has been exploring the relationship and conflict between humankind and nature. His dramatic images of burning taxidermy animals elicit a strong emotional response, triggering an immediate reaction from the viewer. The extreme act highlights how humans are violently exploiting nature, and for which we consider ourselves superior above all living things, while questioning our self-perceived right to reign over nature and animals.

Houge has exhibited extensively in galleries and museums in his native Norway as well as in the United States, England, France, Sweden and China. His work has twice been nominated for the Prix Pictet, the global award for photography and sustainability, and his Arctic Technology series was shortlisted in 2005 for the BMW Prize at Paris Photo. In 2015, his Paradise Lost project was shown in three Chinese cities, including the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing. Residence of Impermanence, which explores humankind’s disrupted relationship with nature, has been shown at three museums in 2019.

Question: Please explain your photography and film work recognized as Environmental Art?

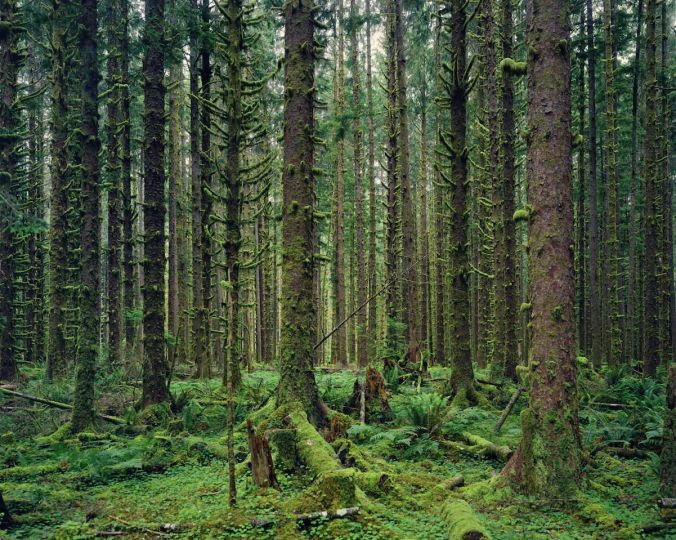

Houge: As a visual artist, I use photography, filmmaking and mixed media to create a dialog about the environment. Over the past two decades, my work has been exploring the relation and conflict between nature and culture. As man `progresses’ in the Anthropocene, we are faced with serious challenges for our near future. Species are going extinct by tens of thousands, forests are disappearing, and glaciers are melting as technology speeds up. We are often finding it more difficult to relate to what is soon to be forever gone. In many ways we have lost our deep connection to both Nature, animals and ourselves in the past couple of centuries.

My latest series `Residence of Impermanence` explores our relation to animals and how we may have forgotten just how important they are to us in many aspects. By making a performance in burning old trophy animals, I wanted to create dialog as to what taxidermy (and the wallpapers they are burned on) actually represent. This work is to provoke feelings and personal references in the viewer. I am hopeful by inviting the audience to reflect on where we are now as a race, and that they will reflect on the challenges where we are facing. Viruses are also being `discovered` in areas where we humans are not supposed to be, as humankind’s taming the natural world can have reverse consequences. Man’s urge to conquer nature has its consequences.

By spending many years on a project and becoming quite obsessed, I am in essence trying to understand myself in a bigger picture. Initially through a tedious and meaningful process, to then share my work to an audience through museums and galleries.

Question: What is the meaning of title, Residence of Impermanence?

Houge: The meaning of my title is dual. Residence as to a place to reside, both meaning this form/mould of man-made taxidermy which the animal skin is stretched over, creating a kind of symbolic limbo state and a partly perverted picture of how we want nature to look like, as well as a reference to this delicate planet we ourselves reside in (and so far the only residence we have to choose from).

Impermanence is that which is obviously not going exist forever and only temporary. It is fluid and fluctuating, as everything else around us, and should not be taken for granted. This word, I believe, is drawn from teachings of Buddhism, and a great reminder to me of being aware and grateful, but also that what we have around us may be gone very soon.

Question: The element of fire is prominent in Residence and also used in the development of some of your other works. What is the significance?

Houghe: I think we all have a little pyromaniac in us from childhood. This is a natural and mesmerizing fascination with an element which destroys, but also can give new life. It can hurt us, but also comfort.

Fire was what helped us humans to evolve. It helped us stay safe from predators and cooked our food. I think even a lot of language was developed over the fire. Fire is used in all cultures as something of a necessity to bring safety and hope. It is an element which is not always easy to control and can harm us in a big way (ref. forest fires around the world).

The element of fire was very difficult to photograph, which was discovered in my process of burning over 100 animals and all the money and labour that was involved. I had to let go in the final stage. Therefore, letting the fire create new life and form in the animal, which was outside of my control. In this ritualistic performance, I really did feel that I was setting the animal free (from the limbo which Man created), at the same time. Existentially closing a circle if you will. This was a very moving and spiritual part of the performance for both me and all the people involved in the burning process.

At the same time, as I am setting the animals free and giving them `new life` and expression, while taking it off the market for further sale.

There is a famous taxidermy shop, Deyrolle, in Paris, which had a fire, and the animals burned with a backdrop of huge wooden walls and columns representing historically a higher elite. This prompted a huge outpouring of support and contributions for a complete restoration. This event inspired this body of work.

In my `Darkness Burns Bright` series, I burned large cow skins to give an organic effect on these `predator on prey’ pieces together with beeswax, ashes, blood and twenty-four carat gold leaf. Again, I am drawn to fire as something destructive, but also lifegiving and real.

Question: What was your process in creating this series? How long did it take?

Houge: I collected the taxidermy animals for seven years. This was an expensive collection, that required huge loans, and for which I took chances economically.

I started with the purchase of the smaller animals, which were purchased at local auctions. In this process, I started understanding exactly what type of animals I wanted, with the specific postures and expressions. I also bought rare trophies which needed to be repaired before burning (as the animals are decomposing since the day they are killed and `stuffed`. It was not easy to build this collection and I started buying from international auctions where they had the rare and specific animals I was looking for. Trophies were given to me by the wives of deceased big game hunters also. I became obsessed with this, knowing in the end, that I would destroy it all. To me it all became a lot more cathartic than I had first imagined.

Destroying something this expensive and collectable (by certain types of people) enrages some people, while others find it very inspiring. The range of emotions the viewers are invited in to is amazing as we all have some personal history with animals either as pets, food and culture from childhood. All the symbolism and characteristics we put on animals to understand ourselves through fairy-tales, mythology religion and cartoon sits so deep in us and we tend to forget this.

Some people have sent me very nasty emails, while and others have really been moved to tears by the series and the film. Many people have told me that they have been inspired t to take action in their own lives and be more conscious. Creating a dialog like this through art I what I genuinely hope for. It opens the possibility and remedy for change and awareness in not only our relationship to animals, but environment and nature in general.

I went through three photographic periods with this series and burned in different locations with a team of several people. The wallpapers, used as backdrops, were from House of Hackney; represented imperialism, colonial ideals and the conquest of nature by the wealthy. Each of the background wallpapers were picked out to the specific animal. I was sponsored by real estate firms, who lent me abandoned buildings where I could burn and used a Phase One digital camera (150-megapixel digital backs). I had a lot of interest from many sources and people, as this was something new and radical. It opposed old ways of thinking and I believe created something meaningful and provocative. This outside assistance included a great crew which I could never have done this project.

Question: Discuss mankind’s conflict with the natural world, and the taming of the wild?

Houge: Mankind’s conflict has grown stronger as we have progressed in culture and technology. There is less than 3 % natural area covering the planet. We literally stand in line shoving each other off the mountain getting to the top of the world’s highest (and holy) Mt. Everest. Plastic waste was found in the deepest point in the ocean (Mariana Trench) when we were finally able to reach those depths and animal species are disappearing forever after so many millions of years of evolution. Man’s ignorance and greed really fascinates me.

We humans are destroying that which we not only are a part of, but also totally dependent upon. We often see nature as a commodity–something nice to have and good for the short-term economic value, not something necessary the survival of our own species.

Question: The exhibit, Residence of Impermanence, is presently at the California Museum of Photography through August of 2020. What are the future plans for this series and exhibition?

Houge: The future plans for the series is an exhibition at Fossekleiva Culture Centre & Gallery and art collective in Norway this coming November. New work will also be shown

This will be the seventh viewing of this touring exhibition series.