The ninth edition of the Lianzhou International Photo Festival lives up to the high standards set by previous years. Our thanks to festival director Duan Yuting for presenting us with 60 Chinese photographers and their work on the theme “Farewell to Experience.”

The atmosphere of Chinese photography today is strong, distinctive and, regardless of subject, reflective of an anxiety and confusion. Sometimes that feeling is explicit, sometimes it seems to be just beneath the surface, and other times it appears to enter their work almost unconsciously.

After the years of creative madness that followed economic liberalization, followed by an equally creative yet less cathartic period, Chinese photographers now seem to be reeling, a development owing itself to the brutal acceleration of history that has made China into a global economic leader. A transformation so sudden had to leave its mark. The Chinese dialectic, from the ancient to the modern, exhibits the desire to erase the past, and it would seem this desire troubles many sensitive souls, including photographers. These photographers are condemning this headlong rush, like Du Zi (Scar) who takes a strong stance against the destruction of landscapes, or the more distant Chen Xiaofeng (Placing Plants) who can no longer bear the poor plants abandoned in the corners of buildings and apartments. So does the work of Lau Chi-chun (Landscaping Artifacts), who salutes triumphant Nature.

Others use more or less metaphorical means to withdraw from the world around them, projecting themselves into future, like Li Zhi (Moon) with his reconstruction of the moon, and the dreamlike spaces of Hei Wei (The Little Universe). China’s past is on display with the splendid photos of the Henan Province by Jiang Jian, or Li Jie (When Play is not Play- a Cultural Imagination through Time and Space), the moving photographs of Zhao Gang (My University Life), and the work of curator Chen Xiabo (Faces of Old Times) who shows us how China was before.

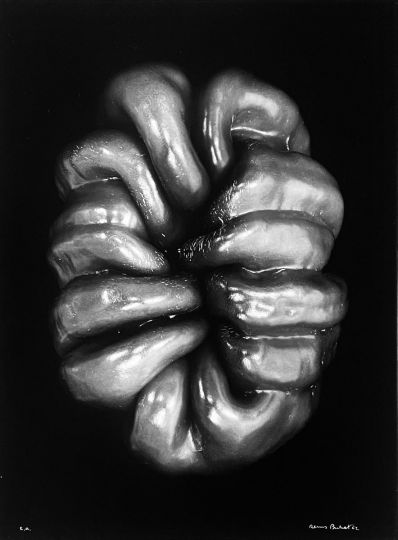

Not to mention the Chen Wenjun’s glorified statues of Mao (The Sun Also Rises). This unease with abrupt change is also reflected in the feeling that one doesn’t exist, or rather that the new lifestyles preclude regular human relationships, as in the work of Ge Pei (Don’t Look At Me) and Fu Weixin (Chinese TV), which catches television personalities with their eyes closed. The same unease can also be seen in the photographs of Meng Jing and Fang Her (Love Hotels) in their reconstruction of rooms in a brothel. Li Zhaohui (Specimen), shows us what we’re made of—very little, once we’re taken apart—which Wu Qi (Rubik’s Cube-Resources) demonstrates in a different way.

The Lianzhou festival had other photographers worthy of being featured here, and maybe I’ll find the opportunity to do so in the future. Chinese photography is alive and well. Each year new talents are discovered, artists for whom photography is a difficult moment endured for a real result.

Michel Philippot