His name is Charles Martin.

He send us these photographs along with this text.

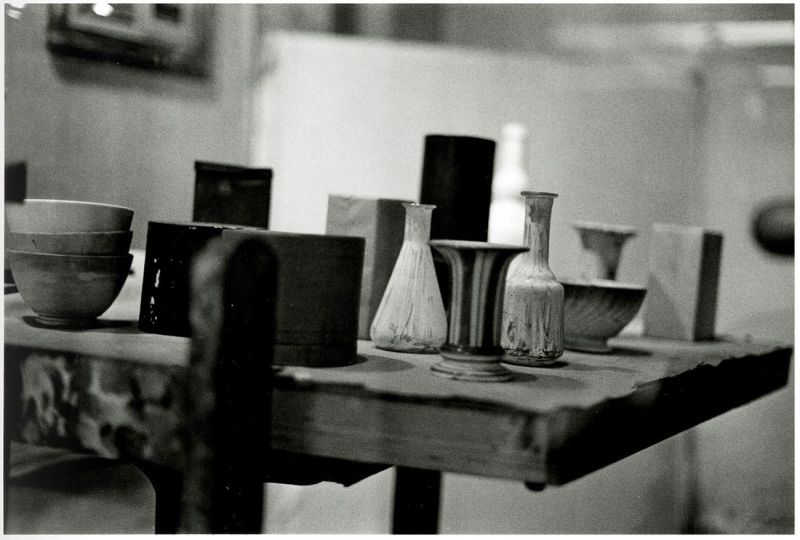

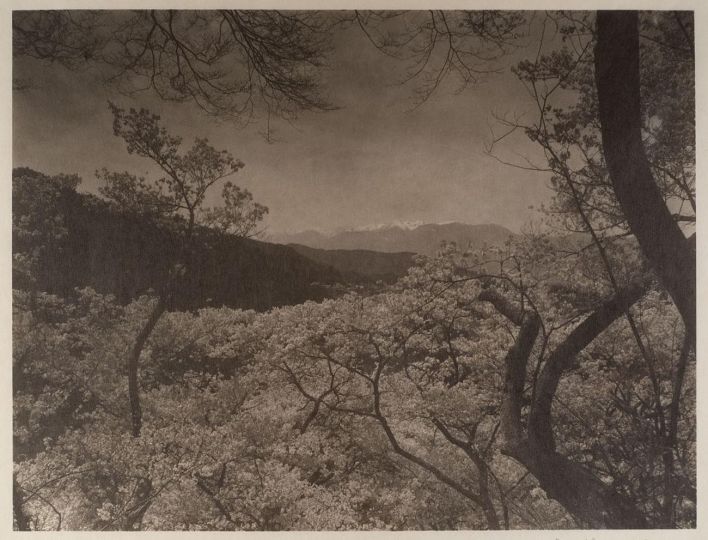

Henri Cartier-Bresson often referred to geometry, so evident in his photos, as essential to visual art. People delight in form. Alfred Stieglitz, photographer and advocate of art, was famously appalled at the idea that the power of his photography came from its subject matter. Stieglitz wanted to show that photography could be more or less free of reference. Reformulated, the thought might be that sight, itself, can ultimately be the primary subject. What do people really see in a photo? A trustworthy explanation of the photographer’s relationship to subject matter? Or an image?! Quite a few of my photographs I call “Glass Constructions” – reflections not usually in mirrors, but in windows and other spaces of glass. Rather than being “mirror images,” they are transparent labyrinths drawn from surfaces, interiors and reflections.

Photography has come to me in starts and stops, a few leaps forward and an occasional step back. I methodically applied myself to it while in graduate school in Afro-American Studies before my first visit to Brazil, but the first photographers in my life were my parents. Mom used automatic cameras and Dad amused himself with a thirty-five mm Exacta and a Rolleiflex that I still have. He wanted a Hasselblad, too, but balked at the price. A few neighbors had such cameras. Mostly they did not use them, and family photos usually came from the automatics. My father, embarrassed at the site of my mother using so simple a tool, gave her a RolleiMagic, an auto exposure camera, essentially a point and shoot Rollei. Though she accepted the camera, she preferred and continued to use the simple Kodak, which is where I started, too. The Instamatic 404, with its wind-up, spring-loaded film advance, was for years my ready recorder.

My dad turned a corner of the basement into an occasional lab, a darkroom with faint yellow safelight that dimly showed the contours and objects of the room. Prominent also was a timer with luminescent hands, essential for observing the appropriate lengths of time. In the darkroom, Dad unspooled the film from the cameras and processed the negatives in canisters before hanging them to dry from overhead pipes. The next step, usually days later, was printing. People speak of the magic of seeing the image come up on the paper submerged in a chemical bath in the developing tray, but for me the interval was simply boredom, with the interesting part of the experience being watching my dad. Family photos—by any of us—sometimes went into the scrap books that my mother meticulously kept and labeled in her handwriting. My older brother, Henry, didn’t much get the photography bug, but his art connection was criticism and one of his first books was on the sculptor Arman (who I later photographed on occasion).

Portraits that I have taken are done by access and fortuitous chance, encounters with both friends and strangers, improvised and carried out quickly. Of many possible definitions, for me portraits primarily are records of moments of complicity: the person sees that the photographer is up to something, and the person allows the image to be. Portraits come through seeing people, not knowing them. Would you say that the portraits here tell which of the figures I knew and which I did not? Walking one evening in the Village, New York, I crossed paths with someone whose face I knew only from of his work. “Duane Michals!” I said in surprise. He stopped and questioned, “Do I owe you money?” I laughed and said “no.” I didn’t want to bother him, but I asked him if I could take his picture. “I will not take off my clothes,” he replied, again with humor. I asked him to move a few feet into better light and he did. Four or five snaps, and I thanked him, and we went on our ways. A few weeks later, this time with my wife, I ran into him again in about the same spot. I introduced my wife to him and have never happened upon him again.

At a gallery in New York, I asked a question about a photo I was looking at, and the receptionist answered by going into another room and bringing back with her the photographer, Frank Horvat. We chatted briefly and, at my asking if I could photograph him, he said he didn’t much like being photographed, but it was okay. I took two exposures – back when I was a Leica M2 user, no light meter, of course—one horizontal and one vertical. I got his address from the gallery and later sent him the horizontal. He wrote back, giving me a photo of his, and asking for more prints of the image I had sent, saying he liked it very much and would use it for publicity. Whether or not he did, I do not know. We did correspond a little, and I ended up, for “Entre Vues” on his Horvat Land website, translating into English three interviews that he had done with Edouard Boubat, Joseph Koudelka and Sarah Moon.

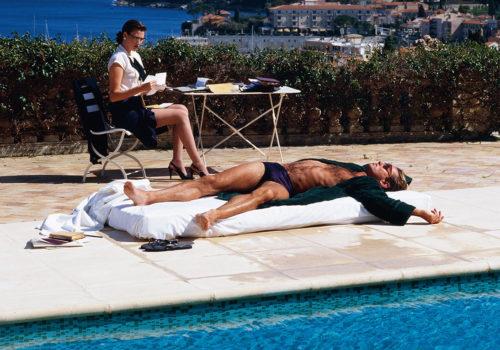

Ed Clark, abstract expressionist artist, was a great friend. Aside from my shows in New York, Ed saw two of them in Paris, which is where we met. Paris was special to him and he spent most summers painting there before returning to New York for the rest of the year. I had presented a paper, “Coloring Books: Black Ideas of Europe,” at the African-Americans and Europe International Conference, at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, February 5-9, 1992, organized by Michel Fabre, a professor who wrote a biography of author Richard Wright. About a year later, again in Paris, I showed photographs to Fabre, and one of them, taken in New York, was of poet Ted Joans. Fabre asked if Joans had seen it, and I said no. He told me that Joans was a regular at Café Le Rouquet, gave me the location, and suggested I go there to show Joans the photo. When I did, Joans was in the company of Ed Clark and some others. Ed and I became friends and, back in New York, after finishing a day of teaching Comparative Literature classes at Queens College-City University of New York, often I would drop by Ed’s place, around the corner from the Flatiron Building. Usually I would at some point have a look into the studio in the back to see what he had been painting. One day I asked him if anybody had ever done a movie about him. He replied that someone was always saying they were going to, but no one ever did. I told him I was going to do it, he said okay and suggested people who might be interviewed. I convinced a director, for whom I had once shot stills, to be the cinematographer for the project, and despite his initially finding it odd to be directed by his former set-photographer, the documentary was made: A Brush with Success.

Cameras have accompanied me since childhood and stay within reach, occasionally capturing a dream or a nightmare concocted from glass, metal, water, sky and light.

Charles Martin

[email protected]

“Charles Martin – Umaxxi”

https://charlesmartinumaxxi.godaddysites.com