La geometria e la compassione. Ferdinando Scianna and his images that make us look.

Geometry and compassion seem to have little in common. Or maybe not. It’s just that to discover the connections, we need to be able to look at the world and into it: it’s not enough to know that things exist, they can’t be ignored. And they have to be discovered.

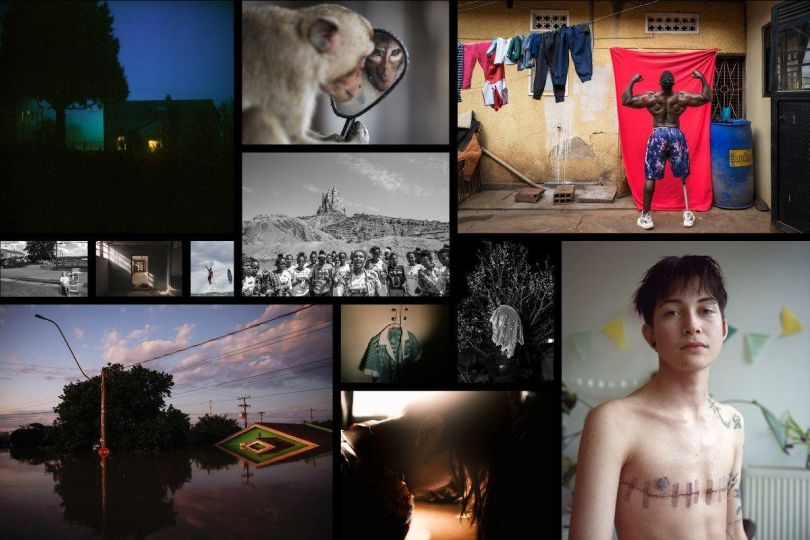

Sometimes this leads to a sudden and painful awareness of facts that are known but not considered or it opens up new avenues of thought, connections, different visions. If this happens, then Ferdinando Scianna has hit the mark (as he practically always does) with the exhibition La geometria e la compassione at the CMC – Centro Culturale di Milano, with sixty original prints and texts for a meditation on what we often ignore, know, but do not look at.

It is a story that tries to give voice to pain and injustice, as well as to the human desire for happiness that persists despite everything; as the author explains: “Nothing can be expressed without geometry, without form, and the form of every man and woman is the pursuit of happiness. The pain of others provokes compassion in us because it distances us all from the right to be happy”.

It is an exhibition that touches and stirs emotions because the photographer did not limit himself to documentation. There are many images taken after the actual reportage, beyond the work. “They are the most personal, most heartfelt photographs”, he tells us. “And a big mistake of mine is that I did it too little”.

Paola Sammartano : Geometry and compassion are two concepts that seem unrelated: how do you link them?

Ferdinando Scianna : In a way, I had already used this combination to title sections of certain more complex exhibitions, when I was dealing with things that had to do with, let’s say, the pain of the world. I had called one Geometry and Compassion, after La géométrie et la passion, the title of my exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris. A title that for me was a kind of homage to Cartier-Bresson, who believed that content cannot be separated from form. As I say in the preface to the exhibition at the CMC: ‘Nothing can be expressed without geometry, without form. The form of every man and woman is the pursuit of happiness. The pain of the world provokes compassion. And in it, one discovers the longing to seek happiness.

Why geometry?

F.S. : Nothing can be said without geometry, without form, without a need for aesthetic communication, because geometry is a kind of metaphor for order, for composition. In one way or another, all discourses on beauty come back to geometry.

When I was confronted with situations that were, so to speak, complex, I had different reactions. But the only real crisis I had was during a reportage when I was horrified by what I had in front of me, and I asked myself, what it means to be a photographer? But while I photograph what distresses me, I still pay attention to the composition. And not just instinctively, because it is a kind of ethical duty for anyone who has to communicate something. If you are a writer, you have to write well. If you are a photographer, you have to do it well. That’s geometry.

And compassion?

F.S. : It took me a long time to come to this conclusion: I think that the, shall we say, deepest ontological, existential datum of humanity is that everyone wants to be happy.

When you are a baby, when you are cold you cry because you want to be covered. When you are a child you want to play to be happy. And it happens that when you meet pain, the death of others, the suffering of others, it pains you. And that interferes with your need to be happy. And so compassion is a way of trying to restore a balance that allows you to be happy again. So, it is something you feel for others and for yourself.

Is it more difficult to photograph joy?

F.S. : I think that one of the ideological-cultural problems of concerned photography ended up producing a kind of distortion: at certain times many of us thought that it was necessary to take a certain kind of photographs in order not to betray truth, justice, equality. With the result that a culture of beauty, joy, happiness was missing. I’ve been working for a long time on this exhibition. At a certain point, I said to myself: how much suffering. But have I photographed joy? And I started looking: luckily I have some.

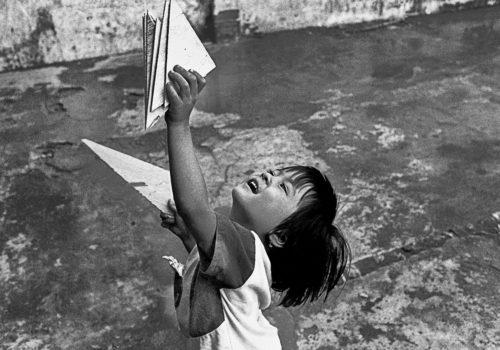

One example is the cover of the exhibition catalogue, because it is a picture that does not even look like one of “disperanza” (an extraordinary term, used by poets and writers, because it speaks of hope in despair), it looks, instead, like hope.

I photographed this little girl in a Save the Children centre in the former Saigon (Ho Chi Minh), where street children, without fathers or mothers, without homes, were brought together: here they were sheltered, and protected. This place was both a shelter and a prison, but this child found some pieces of wood there, and who knows what sparked her imagination. She was running, and maybe they were ships for her, maybe something else….

The genesis of the exhibition was the decision to accept Giovanni Chiaramonte’s invitation, a few months before his death, to carry out a project of meditation on the theme of grief. How complex was it?

F.S. : A few years ago, Marco Belpoliti asked some painters, writers and photographers to write about compassion for his magazine. It was natural for me to make a kind of photo-text, in which the texts were not intended as captions for the photos, but as laconic reflections useful first and foremost to myself. There were 16 photos, which are also in this exhibition at the CMC, and like the current project, they are an attempt to transfer all the questions that life and the experience of suffering pose to you, and that you try to resolve in the contradiction and clarification of how you approach them. Two years ago, Giovanni Chiaramonte suggested that I work on this project. Unfortunately, Giovanni died before he could see it realised. So, this is a kind of homage to him and to Angelo Scandurra, who translated that first photo-text project into a small book.

There are 55 photographs on display today. The exhibition (like the book that accompanies it) is divided into chapters on themes such as misery, illness, catastrophes, violence, emigration, marginalisation, loneliness and death. Does it bring together the words and images that marked your encounters with a profound vision of the world?

F.S. : A vision of the world with its contradictions. Perhaps also a slightly distressing view of the world. I was in Ethiopia, during one of the country’s recurring and devastating droughts. In a camp where people were arriving by the thousands (and dying at a rate of 60 a day), there was a Red Cross tent, and I found myself photographing the brutal process of ‘selection’ between the children who needed urgent intervention and those for whom it was too late. It was something incomprehensible, something horrible to me. I was in a crisis, wondering about the meaning and usefulness of photography. I was about to turn back, when I felt myself following my steps. I asked myself: where are you going? Then I realised I was hungry and wondered where I could eat. I realised that I could escape the pain of others, but not from my own human reality. And that taught me that you cannot change the world with your fragility.

But I could also not run away either, I had to do my job as a photographer and I had to do it well, trying to put my compassion and my pain into photographs.

What is the point of telling the world?

F.S. : For nothing. It serves you and it serves some mysterious and rare person who meets your story and is mirrored in it. If anything, the world has changed my photographs, but that does not take away from the fact that there are things that certain photographers have done that have nourished my vision of the world, both ethically and intellectually. Not to mention literature: you are thought of by the books you read.

But it does not change the reality of the world, history happens. And this is bleak, it can lead to nihilistic results. But it doesn’t. At least not for me and not for many people, because you can say there is nothing to be done, but at the same time you are outraged by what you would like to see change.

Photography does not have the power to change the world, but it can help us see what we often choose to ignore, and the photographer’s job is to try to make it perceptible to the viewer.

It is rather like the attitude of the protagonists of two well-known novels: Il Gattopardo by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa and I Viceré by Federico De Roberto. In both there is an underlying ‘gattopardismo’ (“If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”, Tancredi says in Il Gattopardo). And this is terrible for someone like me or like Sciascia, because we instead think that things should change so that nothing remains as it is. Now De Roberto does not say this in the same way as Tomasi di Lampedusa. De Roberto says it with despair and with this attitude, there is, if not hope, at least “disperanza”.

The exhibition is curated by the author together with Camillo Fornasieri. The accompanying book, with 65 photos, is published by Silvana editoriale per la Collana Quaderni del CMC, with texts by Ferdinando Scianna, Giuseppe Frangi, Marco Belpoliti, Camillo Fornasieri.

Ferdinando Scianna, whose activity and authorship as a photojournalist led him to be the first Italian member of the MAGNUM Agency, presented in 1982 by Henri Cartier-Bresson, has been alternating fashion and advertising photography with reportage and portraiture since the 1980s. And today he also creates writings and books that make us reflect on photography and the act of photographing.

Text and Interview by Paola Sammartano

Ferdinando Scianna. La geometria e la compassione

From November 14, 2024 to January 18, 2025

Centro Culturale di Milano

Largo Corsia dei Servi 4

20122 Milano

Italy

https://www.centroculturaledimilano.it/

https://www.centroculturaledimilano.it/ferdinando-scianna-compassione-mostra-di-fotografia-60-opere/