« In this world

We walk on the roof of hell

Gazing at flowers » – Issa, Japanese poet (1819)

How does a young Frenchman, born during World War II in a good family, the son of a civil servant posted to Morocco, become a photographer?

His itinerary, off the beaten track, and his fascination for the image began when his parents sent Bruno Barbey to a Paris boarding school. “ I was a dunce and a thwarted left-hander,” he remembers now, sitting at his long kitchen table decorated with blue-and-white Moroccan ceramics, in a Parisian house where he also works.

At the Henri IV high school, he felt ill at ease within the constraints of an education that to him seemed rigid and formal. He skipped classes but made lasting, close friendships with future filmmakers Eric Rohmer and Barbet Schroeder. With them he snuck out of school to spend hours at the Chaillot Cinémathèque discovering, among others, the work of Italian neo-realist filmmakers.

After somehow completing high school, he decided to become a photographer. But at that time there was only one school of photography in Europe, the School of Arts and Crafts in Vevey, Switzerland. He started school in 1959 but became bored again, as the courses were mainly tailored to advertising or industrial photographers.

What he wanted to do was to see the world. During the lessons that he took when he was 16 to get his flying and parachuting certificates, he loved the sense of space, freedom and solitude that came from technical mastery , the possibility of discovering the world from new perspectives. Fascinated by the adventurous model of writer Antoine de Saint Exupéry, he felt as if he too was a surveyor of clouds.

With his head in the clouds but his feet well anchored to the earth, Bruno Barbey would bring to his chosen profession the same sense of freedom and openness, of intuitive curiosity and rejection of conventions.

But unlike Saint Exupéry, Bruno Barbey is much more comfortable with images than with words. He speaks little, almost reluctant to voice his own opinion but attentive to the views of other people. He possesses a modesty that is rare among photographers, and a patience that will serve him particularly well in his travels in the Middle East, especially in Morocco, where image hunters may be regarded with suspicion and where photographs must be earned.

In a film by his wife Caroline Thiénot-Barbey on Barbey’s work in China, we see him approach slowly, stealthily, a group of older people dancing in a small square. A little old lady is knitting while she dances. Gradually, smiling a lot, he manages to blend into their group and to photograph. Everything appears to be done with their consent. He takes his time, adapts to their rhythm, and does not force anything. He is tall but does not seem to take up much room. And his subjects seem happy with the process. For Bruno Barbey, photography is above all based upon give-and-take.

His first reportage, completed in 1962-1963, is on the Italians. “My main goal in the early 1960s was to work on Italy,” says Barbey. “I photographed there when I could, over several years, sometimes on assignment but mostly on my own. My goal was to try to capture the spirit of the place. I was fascinated by the filmmakers of the new Italian realism such as Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Michelangelo Antonioni, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Luchino Visconti. At the time, some parts of Italy were very poor and there was a great division between North and South. »

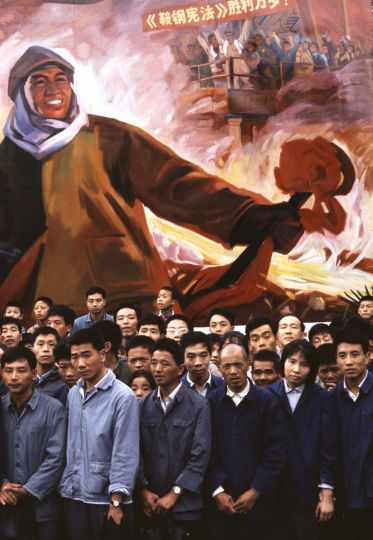

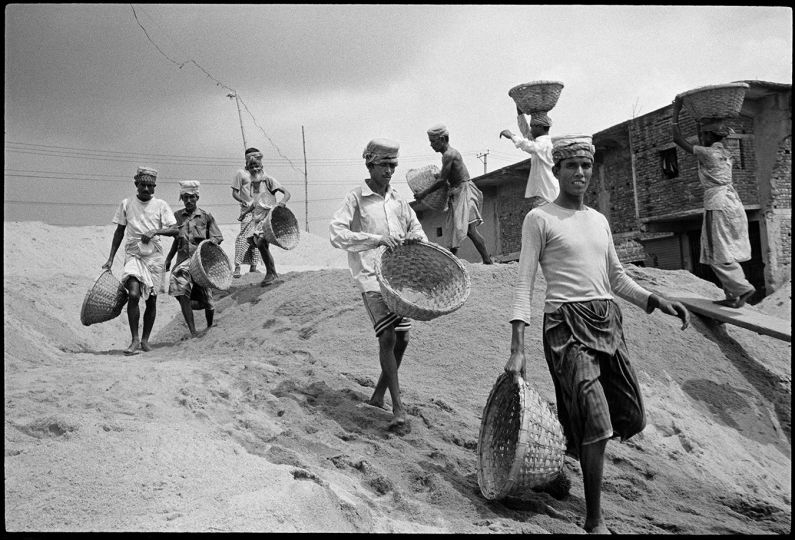

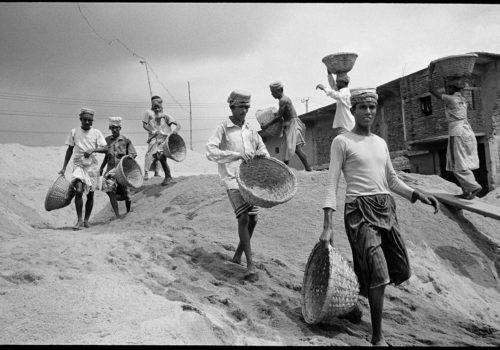

Like Robert Frank’s The Americans or René Burri’s The Germans, this series is intuitive, fresh and energetic. It serves as an initiation, discovery of self , discovery of his own photographic language, and discovery of the other. In 1964, the project opens him the doors to Magnum Photos, the photo agency where he remains to this day. There he discovers photojournalism and goes to cover conflicts in Nigeria and the Middle East. He reports on the events of May 1968 in Paris and Tokyo (and much more recently covers the “Umbrella Revolution” in Hong Kong (which used slogans of May ‘68). In 1971 he does a reportage on the Vietnam War, the last to appear in Life magazine before it ceased publication. He photographs in Cambodia, Jordan, Egypt, Iran, Ireland, Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates, India, photographs the return to power of Juan Perón in Argentina and the tragic story of Salvador Allende in Chile. He is in Phnom Penh when the Khmer Rouge encircles the city. He photographs China during the Cultural Revolution as well as Syria and the Palestinian refugee camps.

Throughout his coverage, he remains passionate about history. He photographed anonymous people as well as heads of state, famines and funerals, wars, festivals, pilgrimages and demonstrations, torturers and also their victims. His assignments gave him the opportunity to visit many countries at momentous turning points. One thinks especially of his long-term work on Poland from the 1980s to the early days of Solidarnosc (Solidarity). “There are rendezvous with history that should not be missed,” he says today.

But while he has covered many conflicts, he is not a war photographer. Unlike many of his colleagues in search of scoops, he generally avoided direct representation of violence. In the spirit of Henri Cartier-Bresson and David “Chim” Seymour, two of the founders of the Magnum agency- he is primarily interested in the effects of conflicts on civilians, especially women, children and refugees. He also photographed child soldiers, that awful invention of the twentieth century, in Africa, Cambodia and among the Palestinians. For him, these vulnerable populations are the real victims of war.

Most important to Barbey are his in-depth studies in several countries, often carried out over many years and resulting in books and exhibitions. He loves to come back to the same places, follow the evolution of a story, and add the density of time to the discovery of space. His layered studies on Spain, Brazil, Japan, China, India, Iran, and West Africa are examples of that method. More than a capture of the moment, for Bruno Barbey photography is often a work about process ad about memory.

The deepest influence, one that remains pivotal to Bruno Barbey’s attitude even today, is his childhood and adolescence spent in several cities in Morocco following his father’s work assignments. “Salé, Rabat, Marrakech and Tangier lulled my childhood,” he recalls. The call of the muezzin, the pounding of the waves, the fragrance of spices remain indelibly engraved in his memory.

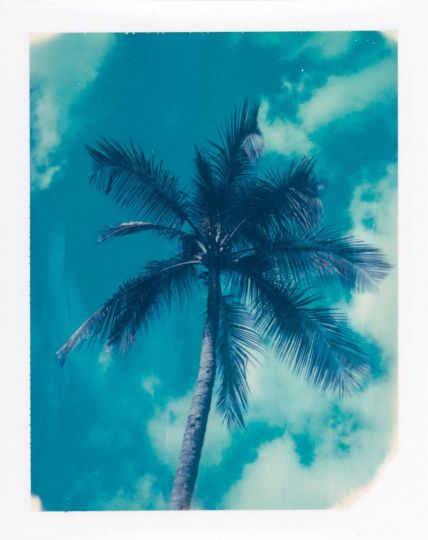

It is this mixture of sensations, smells, colors and sounds that steeped his perceptions. And it is surely Morocco which led to his quick adaptation to color in 1966, during a trip to Brazil, at a time when color was still not reproduced well in magazines and when Magnum had no interest in it:

Barbey became a pioneer of color, exploring all the possibilities of the deep tones of Kodachrome, a film that is slow but resists humid weather and changes of climate. His photographs are replete with the ocher and muted blues of the Moroccan medinas, the hushed tones of the Polish countryside in the snow, the intense reds of Moscow’s large posters and flags … For Barbey, the medium is not simply about surface coloring but a way to recreate the essence of the places and people he meets.

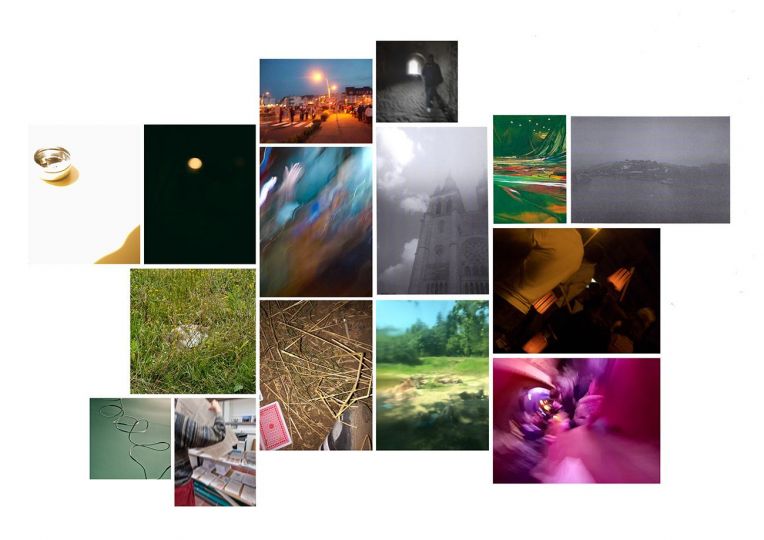

Populated at first by multiple characters, the photographs of Bruno Barbey are today pared down, playing on contrasts of color, light and shadow. He likes the atmosphere of dawn and dusk, and panoramic formats that allow the combination of the human figure and architecture, especially in his work on the mosques of Uzbekistan and Morocco. The use of digital photography has led him in recent years to pursue his explorations into the night, as in his series on young Korean women in the street. “What I like best is to do my own work. Today, I am interested in minimalist compositions and simple elements, » Barbey asserts.

For over half a century, Bruno Barbey has traveled both in space and in time. Keen on accuracy but moved by poetry, his photographs bear witness to the beauty and fragility of our world.

BOOK

Passages

Bruno Barbey

Texts by Carole Naggar

Preamble by Jean-Luc Monterosso

Editions de la Martinière

French/English

24,5 x 32 cm

384 pages

79 €

http://www.editionsdelamartiniere.fr

EXHIBITION

Passages

Bruno Barbey

From November 12th 2015 to January 17th, 2016

Maison Européenne de la Photographie

5/7 rue de Fourcy

75004 Paris

France

http://www.mep-fr.org