Nobody in Bruce Davidson’s Oak Park, Chicago, middle-class family had any interest in the arts, and it was by chance that Bruce witnessed a neighborhood friend developing pictures. As Vicki Goldberg writes in her biography of Davidson, “It was the magic that hooked him, and it hooked him for life.”

“Most boys my age had a dog—I had a camera,” he has said. The camera was at first a Falcon 127, then an Argus A2 35mm that he got for his bar mitzvah. Knowing that the camera was coming he became so excited that he forgot part of his Torah reading in the synagogue.

His first image, in 1949, was a dramatically lit close-up portrait of a baby owl in Trailside, a natural preserve close to home. It won him the Kodak High School Snapshot Contest and, today, he sometimes dreams that he visits the owl again, and that she complains “So where are the prints you promised me?”

Until now Bruce Davidson has been very private about his life, and this biography is the first time he has let anyone in. Through the many conversations he had with Vicki Goldberg during the course of two years, the reader learns about his photographs, but most memorably about his motivations, his emotions, the life behind the pictures, his life with his wife Emily Haas-Davidson and their daughters, and the trajectory that led him to become one of the most respected documentarians of the twentieth century, a man still eager to photograph until now, at 82 years of age.

Even though Davidson’s best known reportages are represented in the book, this illustrated biography is by no means simply a picture book; following the same concept as the volume on Eve Arnold (the first in this Magnum Legacy series), thorough research into Davidson’s home archive, occupying a considerable amount of the space in his Upper West Side apartment, has unearthed a number of never-before-seen archival documents, which further illuminate the main events of his life: an essay on photography written while Bruce was studying in Rochester, tear sheets from early publications, story texts, contact sheets, story books, logbooks, family pictures, and so on. (1)

A strong empathy for those marginalized is already present in a series, shot by Davidson while he was at the University of Rochester, of the Light House Mission that was frequented by homeless alcoholic men. His next project, done while he spent a semester at Yale’s MFA program, was on the Yale football team. He focused on the players in the locker rooms and on the benches. His images were about the stopping of time, the players’ moods, their exhaustion, and their reactions: “I wanted to photograph tension,” Bruce commented. Though his images had the appearance of documentary photographs, what really fascinated him was not the action, but the mystery, what went on below the surface.

His intimate, melancholy pictures of the Walls, an old couple from Arizona, done in 1955 while he was in the military, constitute his first fully realized story, with deep shadows and an emphasis on the slow dance of gestures. The images depict the long-lived intimacy of a couple who are reaching the end of their life. It is surprising how the Walls let the young man into their life with no apparent reservations.

While he was posted to a counterintelligence unit near Paris in 1956, Bruce photographed Madame Fauché, the Parisian widow of an Impressionist painter, in her Montmartre garret, walls crammed with her husband’s paintings, and on the streets and markets that they walked together. With her frail silhouette in a black coat and hat, he saw her as key to a past full of artists such as Matisse or Gauguin, a world he would not have known without her, and of which she was one of the sole survivors. The photographs have a soft, lyrical quality, and because he stayed with his subject a long time—something that would come to define his work—the images build the story in a cumulative way, unlike Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moment.

When Bruce was discharged from the army in 1957, he started working freelance for Life magazine but did not feel at ease with the kind of work that they were offering. Early in 1958 he became an associate member of the photographic cooperative Magnum; he would remain a member of the agency throughout his life.

Sam Holmes, Magnum’s picture librarian, told him about a Clyde Beatty tent circus operating in New Jersey and while scouting the place, Bruce chanced upon Jimmy Armstrong, a dwarf. His famous photograph, dark and deep, of the man in white makeup standing alone outside a tent, lost in thought, smoking and holding a bunch of paper flowers acutely reflects the loneliness of an outsider, a topic that few photographers would touch until Diane Arbus.

In 1959 Bruce approached a teenage Brooklyn gang, the Jokers, whose violent acts had made the news. He managed to gain their trust and stayed with them for a year, shooting intimate pictures of their life on the street, on a Coney Island beach or in Prospect Park. Then twenty-six years old, he felt a deep connection to the lost youth; “I wasn’t so much older than these kids but I could feel the emotional isolation,” he later commented.

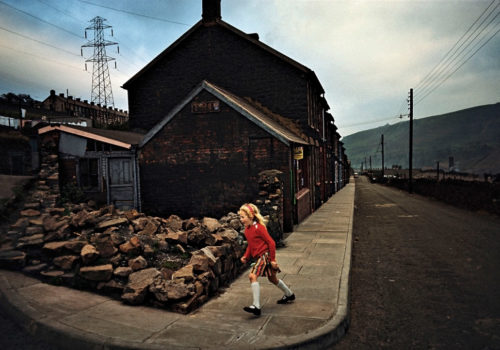

The Brooklyn gang images were seen by Alexander Liberman, Vogue’s art director, and led to a short stint in fashion photography. Several Magnum assignments followed: a group assignment to photograph the filming of John Huston’s film, The Misfits, where he struck up a friendship with Marilyn Monroe; and an assignment from The Queen, a British magazine, to photograph in England and Scotland. Shooting in low light, he produced grainy prints full of the melancholy and mist, the greys and blacks, of the London streets and the Scottish landscapes. He would go back to England and Wales five years later, making lyrical, romantic portraits of miners.

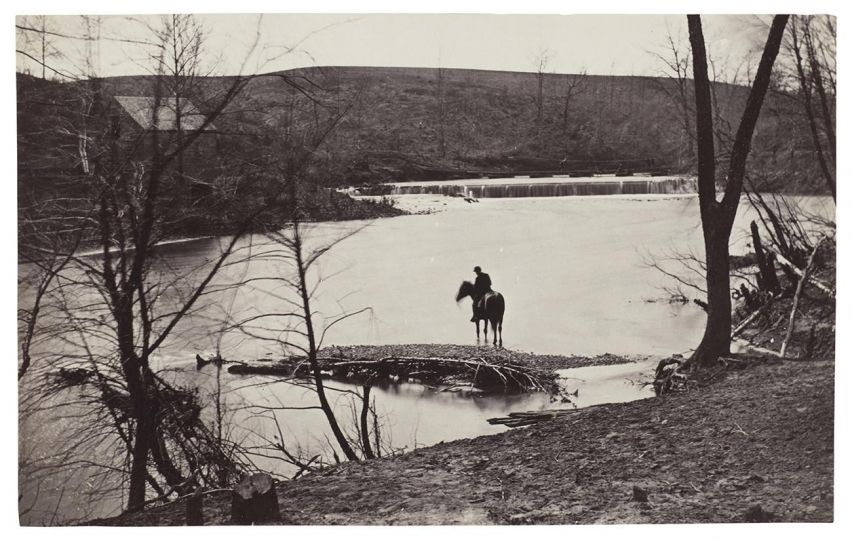

In 1960 Bruce won a Guggenheim grant to photograph ‘Youth in America’, and John Morris, then Executive Editor at Magnum, asked him to cover the Civil Rights struggle. Though he did not consider himself a political photographer, he accepted, walking almost every protest march with the volunteers. He went to Washington for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in 1963, and made memorable photographs, including the 1965 image of a young black man, during the Selma to Montgomery march, who had written the word Vote across his forehead. The image came to be seen as symbols of the movement. Unlike news photographs, Bruce’s images were not focused on the violence but were more intimate and exploratory.

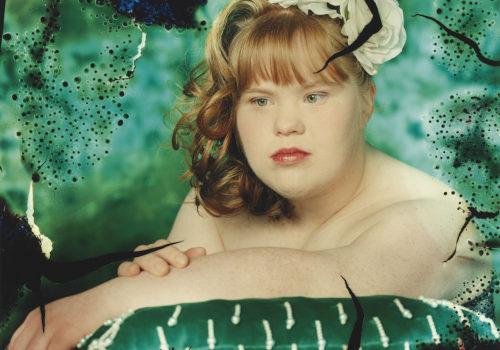

His experiences photographing the Civil Rights movement had made Bruce more aware of the life African Americans were leading in America, and when in 1966 Sam Holmes alerted him to a possible story on East 100th Street in Harlem, he followed up right away. With the permission of the Metro North Association, he started photographing with a 4 x 5 large format camera with a bellows, placed on a tripod, a kind of camera that had not been used before for documentary work. Promising his subjects copies of the photographs, he was able to shoot inside apartments as well as on the street. His pictures are imbued with dignity, and he saw that the block had ‘a spirit that could not be broken.’ After winning a National Endowment for the Arts Grant– the first ever awarded to a photographer– he was able to pursue his work in Harlem, eventually publishing the book East 100th Street in 1970 to great acclaim from photographers as well as to great controversy from critics.

In 1980, after working on projects on the Jewish Lower East Side, including portraits of the Nobel Prize-winning writer Isaac Bashevis Singer, who lived in the same building he did, and the Garden Cafeteria, frequented by Holocaust survivors, he started photographing the New York subway in color. At that time, the subway had just recovered from near-bankruptcy, and it was crime and drug-ridden, with car exteriors and interiors covered in graffiti. Carrying a small album filled with previous photographs, Bruce started taking portraits, always asking for permission from the riders, and then sending them a small print. He used a flash, which produced dark backgrounds and strong contrast, as well as a jolting, fluorescent array of colors.

In a shift from portraits to nature, his next project was about Central Park, where he photographed between 1992 and 1995, coming back day after day in various kinds of weather. He had a triptych in mind about nature in big cities: New York, Paris, and Los Angeles, and photographed nature hidden within the cities’ walls.

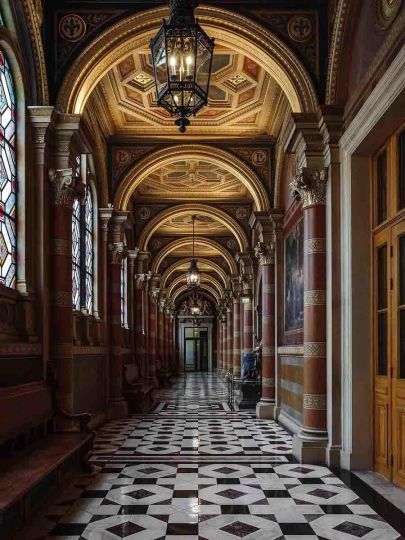

Today, as he works on a project on the Natural History Museum in New York, the sense of magic that had been with him from the start remains: “I’m still the kid that took street pictures and loved that I could explore”.

(1) The Magnum Legacy series, of which I am the series editor, embodies an idea first floated in a conversation with John Jacobs, then Director of the Inge Morath Foundation: we thought that biographies of photographers should be as serious as biographies of writers, musicians and painters, and should rely strongly on their archives. The series is produced in collaboration between Prestel and the Magnum Foundation. The next two volumes, on Inge Morath and Josef Koudelka, are in preparation.

BOOK

Bruce Davidson: An Illustrated Biography

Text: Vicki Goldberg

Foreword: Susan Meiselas and Andrew E. Lewin

Inside a Living Archive: Tessa Hite

Publishers: Prestel & Magnum Foundation

http://www.magnumphotos.com/BruceDavidson

http://prestelpublishing.randomhouse.de