The undeniable influence of Kertesz’s Distortions, made in the mid-1930s, on the evolution of photography only dates back much later, from the time of the publication of his fantastic photographs, in 1972, delayed (by his departure to the United States, by the war, by the lack of opportunities). Similarly, the impact of Bill Brandt’s distorting focal length could only become effective when his numerous experiments dating back to the last fifteen years were made accessible to the public, in 1961, thanks to the London publisher Bodley Head.

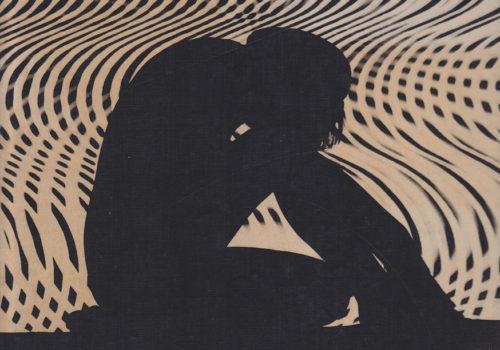

These two books of nude photographs (female; male nudes were not yet even conceivable, even for female photographers adept at nudes such as Ruth Bernhardt, Ergy Landau, Yvonne Chevalier, etc.) opened the way for practitioners of the following generation to whom they taught that one could have fun, do funny, fantastic, new things in one’s photographic practice and that the ways available to them to produce images freed from strict, everyday reality were multiple, almost infinite: from the arrangement, like Zoltan Glass, of unusual or displaced objects on the corpus delicti (M. Marièn, R. Cerf, F. Michaud, etc.) to printing manipulations (superposition, solarization) to the insertion of the photo itself in a more or less narrative series (Sannes, Veruschka). But the first to feel thus liberated in their creation were not, contrary to what one might imagine, followers, rigorous or not, of surrealism; but quite simply photographers, moreover already more or less experienced, inspired by the evolution of pictorial and graphic creation at the end of the 70s. This is the case of the Prague-based Zdenek Virt (1925-2008) who devoted a fascinating volume (Op Art, 96 Aktphotos, ed. Müller & Kieppenheuer, Hanau/Main, 1970), very creative, to subjecting the roundness of his nude photos to the rigors of the precepts of Op Art, an infinite variation of black and white combinations of geometric, curved or angular lines and shapes. The result of these confrontations, most often implemented by projections, presents to our astonished eye new, absolutely unsuspected shots where natural, straight feminine curves and geometric curves harmonize or, on the contrary, clash. [Ill. 1-4].

In a totally different creative vein, the Dutchman Sanne Sannes, whose life was accidentally cut short (1937-1967), author of a highly acclaimed publication (Oog om oog, 1963), owes his marked interest in graphic design and layout, in comics, particularly underground American comics (Crumb), to his studies at the Beaux-Arts; without neglecting the very perceptible influence of the style of the pope of pop art graphics, Roy Lichtenstein, minus the colour.

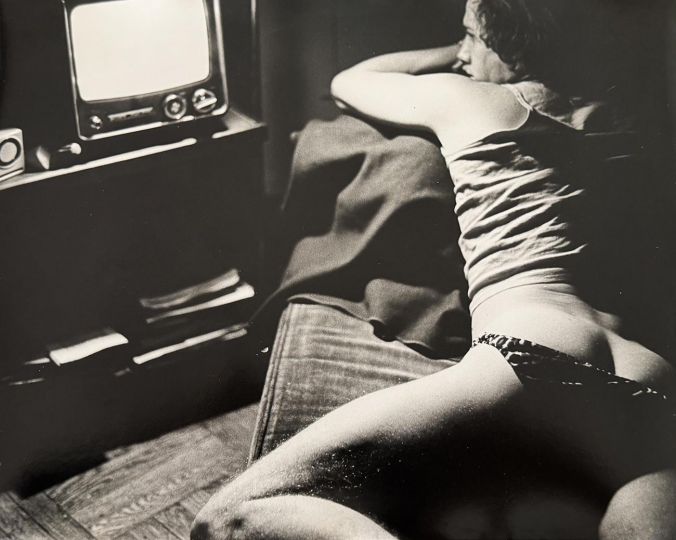

With the complicity of his graphic designer friend Walter Steevensz, in fifteen chapters with a delirious libertarian inspiration, typical of the end of the 1960s, Sanne Sannes offers us in black and white in the unusual format of 17 x 28 cm Italian style [Ill. 5-6], under the programmatic title of Sex a Gogo (Amsterdam, 1969) a jubilant pseudo-story of a good hundred pages with unbridled graphics where female nudity, taken from his photo archives or captured in snapshots during somewhat Dionysian festivities, far from the aesthetic accomplishments of a Lucien Clergue at the same time, or the sexy provocations of Helmut Newton, as only a pretext for an explosion of graphic inventions with no other rule than the arbitrariness of fantasy which make this original and sought-after publication the manifesto of pop art applied to nude photography [Ill. 7-10].

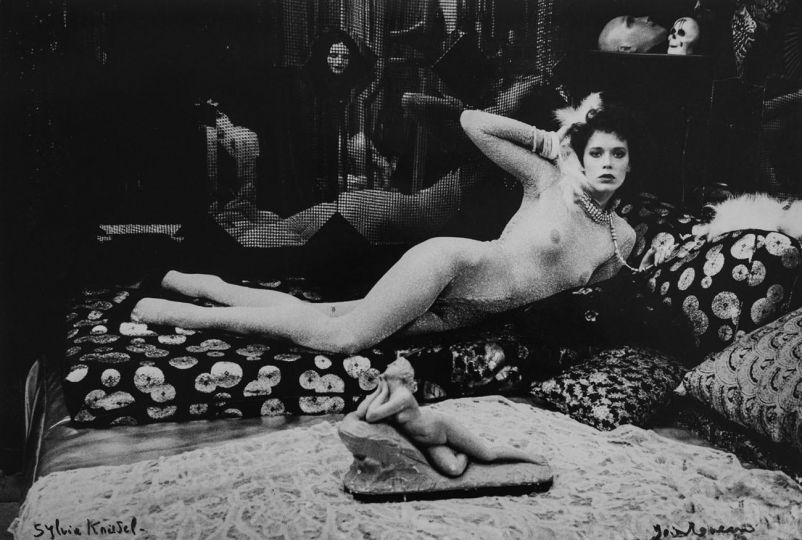

Finally, with his Nude variations (New York, Amphoto, 1977, 96 pp.) [Ill. 11], his last publication, quite marginal in his production, André (de) Diénès (1913-1985) demonstrates that a seasoned photographer such as himself, who, after having published at over sixty years of age ten books of nudes and countless articles in periodicals, has the reputation of one of the most gifted and prolific specialists of the nude, will not deprive himself of publishing an ostensibly experimental essay, undoubtedly prompted by the very recent American publication of Kertesz’s Distortions (New York, Alfred Knopf, 1976). Even if he did not say a word about it, while he was relatively eloquent in the short explanations of his research (For me, it is always necessary to do something difficult and challenging. p. 17), and explicit about the way in which he obtained the original effects that he presented in this book of completely unusual photos, especially for him: coloring (toning) of the prints [Ill. 12], use of mirrors to exploit symmetry to the point of bizarreness [Ill. 13-14], even if it meant generating, not without an easily tiresome spirit of system, images that border on monstrosity [Ill. 15]. As for the distortions themselves (deformations of the subject in all directions, without any stated regularity) which are the exclusive subject of chapter 4 where they are reproduced copiously over a good thirty pages [Ill. 16-19], Diénès dates his research and tests back six years, – well before the American publication of those of Kertesz. As for him, after the distorting mirrors with which he had not failed to produce “a number of photographs of pretty girls”, it was, following a series of fortuitous events, with broken (or not) pieces of glass, – bottle bottoms, engraved ashtrays or large debris, that he experimented, placing them in front of his lens to produce unpredictable alterations of shape; or even by applying irregular layers of synthetic resin, with a random effect, on the external lens of his camera. He thus enriched the vocabulary of photographic art with new processes to alter, modify the native image ( in the same way of gum bichromate prints in the past), in an approach, one will recognize, clearly different from that of his illustrious predecessors; from that of Kertèsz, thanks to outdoor shots that loved freedom, freed from the restrictive link with distorting mirrors, as from that of Brandt, from whom Diénès, an Apollonian photographer if ever there was one, spontaneously freed himself from the tendency to fragment the body (manifest especially in his beach photos of the 1950s).

Finally, animated by a fertile breath of freedom, Virt, Sannes, as well as Diénès, inventors and practitioners of new resources or processes to circumvent, discredit or magnify reality (like their pictorialist ancestors) laid during the 70s, the bases of a mutation which, during the following decade, had upset, with the help of surrealism, − not to say revolutionize, the practice and perception of photography. This is what we will see soon.

Alain-René Hardy

L’ivre de nus

[email protected]