John Loengard is dead.

He was one of the last myths of the golden age of photography from 1950 to 1990. He was the great director of photography for Life and an extraordinary photographer.

I still remain fascinated today by his photo of Henri Cartier-Bresson playing with a kite in the Luberon.

For pleasure, John collaborated for a long time to the Eye of Photography and we held our editorial conferences at the bar of The Carlyle, the hotel on East 76th street. We often talked about his dream, the only one he had never realized: a collection of books on all of Life’s photographers! Imagine!

Look through John’s archives in the Eye: these are pure marvels.

Goodbye John!

Jean-Jacques Naudet

AN APPRECIATION OF JOHN LOENGARD

By David Friend

John Loengard, the esteemed Life magazine photographer and director of photography passed away due to medical complications on May 24. This homage is adapted from the preface to Loengard’s 2011 book, Age of Silver: Encounters With Great Photographers (PowerHouse).

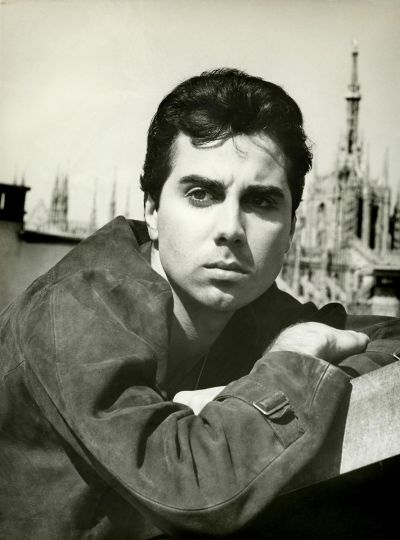

In 1956, John Loengard was a precocious young man, a senior at Harvard, with a knack for making pictures. Life magazine took notice. Its editors began offering him assignments. And, in short order, he’d landed a coveted spot as a staff photographer, carving out a path as a resident artiste—a contemplative, brainy, self-possessed sort who liked to work alone in the field, often for months at time. (His peers at Life tended to do their assignments in the company of a reporter, who would usually double as an assistant, toting the requisite tripod, the camera bag, the coffee.)

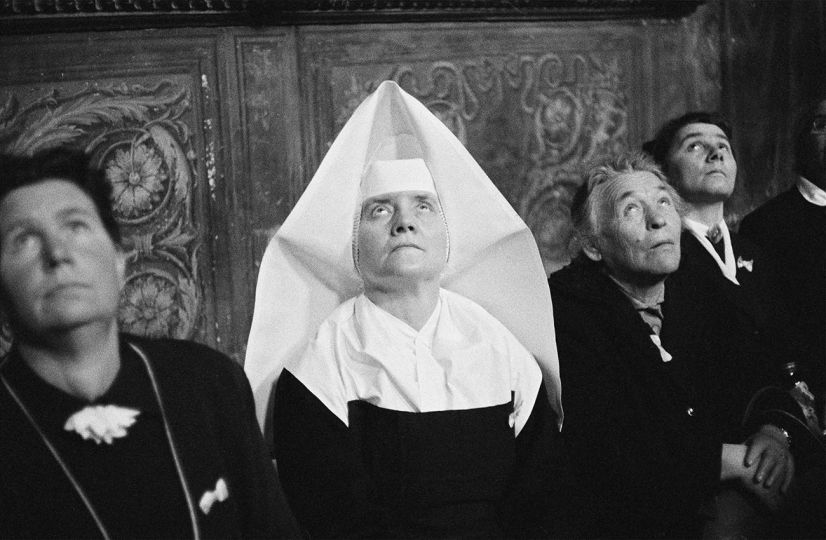

In time, Loengard would develop into one of the masters of the black-and-white photo-essay. His most enduring stories—on the last surviving Shaker communities, on artist Georgia O’Keefe, and on his family’s summer home in Maine—are benchmarks of the genre. And he would excel at environmental portraits that were honest, graceful, and succinct, sometimes spartan; his studies of O’Keefe, writer Allen Ginsberg, and comedian Bill Cosby, among many others, are acknowledged classics. Indeed, during Life’s tumultuous last decade as a weekly publication, American Photographer would brand Loengard the magazine’s “most influential photographer.”

By the 1970s, he had become Life’s picture editor for a series of special editions, and then, after a stint at People, served as director of photographer when Life started its monthly incarnation, in 1978. In that role he would give watershed assignments to many of photography’s giants and helped shape the careers of scores of newcomers. Annie Leibovitz, in fact, has mentioned that it was while shooting a piece on poets for Loengard, in 1980—particularly an image of Tess Gallagher, in costume, atop a white horse—that she reached a conceptual watershed in her work. “The Tess Gallagher portrait,” she has written, marks “the beginning of placing my subject in the middle of an idea.”

During that period, I was a young reporter at Life. Much of my time was spent learning how to produce what were called picture stories or photo-essays. Now a rather anachronistic mode of storytelling—the magazine equivalent of novellas or sonnets or mime—picture stories consisted of sequences of juxtaposed images, laid out over a series of double-page magazine spreads, and supplemented by short text blocks and captions. This interweaving of pictures and text was intended to relate a compelling linear narrative. To that end, I would travel the globe in search of scoops, always paired with a world-class photojournalist. If you could photograph a subject and if it had some newsworthy aspect plus relevance plus surprise, you had a story. And off I would go—always in the company of a photographer selected by Loengard—to places like Oman and Tunisia, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, Syria and Jordan, Israel and the West Bank, Poland under martial law, Newfoundland during a oil-rig disaster, Lebanon and Afghanistan during wartime.

Soon, I developed a ritual. Most nights at 6:30—in the days before 24/7 cable news, the Internet, or mobile devices—I would join a few reporters to watch the evening news for half an hour, trying to stay on top of events we might be covering in the weeks or months ahead. Then I would wander over to the dark corridor of the photo department and plop down on the couch in John Loengard’s spacious, if disheveled, office.

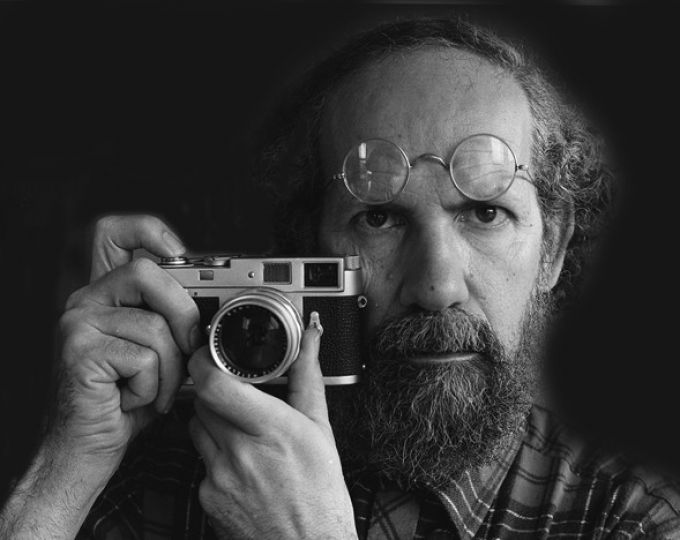

Typically, the imposing, stone-faced Loengard would be leaning back in his chair, his tie askew like his wiry hair. He would be wearing rumpled gray slacks and oxblood wingtips. And he would be holding—just inches from his face, like a paper mask—a black-and-white contact sheet, fresh from the photo lab. Each contact sheet contained a single roll of 36-exposure, 35-mm negative film that had been developed, cut into strips, then printed in positive format in rows of thumbnail-size images. (Loengard hated the word “images” and would wince whenever someone applied the word to a photograph.)

With his face obscured and his head tilted upward, the better to take advantage of the fluorescent lights overhead, he would grunt acknowledgment. (He was prone to the halting mumble, to muffled responses, to pauses that would extend into interminable, Sphinx-like silence.) And while listening to me blather about the news or an upcoming assignment or a particular picture I’d recently admired, he would continue sitting, contact sheet over his face, quickly moving his version of a loupe—actually a Leica lens he used as a magnifying glass—down and up and down the sheet, picture by picture. Occasionally, he would fix me with his piercing steel-gray stare, his sagebrush eyebrows as unruly as actor Milo O’Shea’s. Then he’s nod or grimace or go on editing.

After digesting each contact sheet, he would take a grease pencil and check off the particular frames that might be worthy of enlarging as work prints. Occasionally, he would stop to take an early evening phone call from a photographer in the field, someone just getting back to his hotel room in Europe or calling in after a day shoot in L.A. (In the next office down, his deputy, Mel Scott, was usually still there editing, leaning over his light-box as he burrowed through tight mounds of transparencies.)

Eventually, Loengard would talk—editing all the while. And I would soak up wisdom. He discussed the nuances of stories in the pipeline. He would worry through the hurdles of upcoming shoots. He would explain why a story hadn’t worked—and how he’d known, from the moment the piece was assigned, why it had been destined to fail. He was a man who could spot an exquisitely composed photograph from fifty yards, and tell you how and why it was wonderful. He valued a picture’s surprise and spontaneity over its elegance, its movement and content over its artistry.

From a cranny of a cast-off contact sheet or deep inside a stack of slides, he was forever finding the extraordinary moment that would become a photo-essay’s cornerstone, the picture that told a deeper, subtler story. During certain layout sessions, after remaining mum as other editors debated the photo selection and pacing of an article, he would stop and ferret out an overlooked print, or flip over a nearby print to lay its white underbelly on top of the first photograph to come up with an intriguing new crop, creating a fresh image no one had yet considered.

Loengard would pore over dozens of rolls for a single assignment, recalls Barbara Baker Burrows, the current director of photography of the Life franchise. [Burrows would pass away in 2018.] “Then he’d take a couple of pictures into the layout room,” she says, “and hand the editors one or two pictures and insist, ‘This is it.’ They’d say, ‘John, the photographer’s been shooting hundreds of rolls.’ He’d say, through clenched teeth, ‘This is it.’ He was such a good editor; he knew precisely what should—and shouldn’t—be used in the final layout.

“There was no uncertainty in any fiber of his body. I remember the posture: he’d walk in with this ‘Al-Haig-I-Know-What-I’m-Doing-Don’t-Question-Me’ bearing. He had backbone and loomed large in any room. If he said something, people would listen. They trusted his story sense, his command, his instincts. He knew it all. And there’s no one in my career I’ve ever learned more from.” Loengard, in fact, had been out there in the field for years and so he understood the hurdles. This experience, this wisdom, this eye—and the esteem in which the Life hierarchy, unlike those at other publications, held the taste and talent of the picture editor—gave the photographers, in turn, more stature, more power, more creative force and license.

Loengard was known in the business for his scowling oracular presence, a cross between a rabbinical sage and a tough-love football coach, a Theban seer and a photographic Bob Fosse who oversaw the choreography of every shoot while seeking out and nurturing new talent. He was a solitary figure who gave off an air of studiousness, even nobility, and a glint of righteous indignation. He could appear judgmental and abrasive at times, and was constitutionally unable to suffer fools. He was a pastiche of opinion and curiosity, intuition and experience, skepticism and marvel. He was the dictatorial pater familias and the raw youth fired by an unquenchable imagination.

He was also intoxicatingly engaging. He was refreshingly—and sometimes infuriatingly—counterintuitive. His mind would bore into the heart of a problem, or flip it on its backside to dissect it, or turn it inside out to explore entirely unanticipated facets. “I always felt when I was in a room with John,” insists photographer Michael O’Brien, “I could feel his mind working. His mental muscle was that powerful.”

“He treated photographers as if they were like him—intelligent—not button-pushers,” says photographer Harry Benson. “He took the photographer’s line, often against the [publishing] company, which was a very rare trait. He was a real photographer’s editor. The editors would all be in the room and agree on something and John would smile and then go away and work out the real approach to the story with the photographer. He knew that at Life the photojournalist was king.

“And he was a gentleman. It wasn’t acquired—a manner he’d put on for posh people. It was his natural way of interacting. Even to the crappiest photographer coming in, he’d give some good advice. And he’s always been his own man. He didn’t need other people. He was a lone wolf who went his own way—as a photographer and as an editor.”

Loengard acquired a reputation for encouraging young photographers (occasionally offering an assignment on the spot if impressed by someone’s portfolio and resourcefulness) but also for driving others to tears as soon as they left his office. A few successful photojournalists, years later, profess to still being traumatized by their initial encounter with the great, gruff Loengard. And yet, I found him, down through the years, to be a generous and moral man, a principled soul—kindly and measured, considerate and gracious, devoted and distinguished, witty and wry, openhearted and open-minded.

Just before photographers would leave on a story, then once or twice while they were out in the field, he would goad them, insisting that they attempt not only the improbable and preposterous, but the impossible. His intention was to stretch their limits, to force them to consider every visual possibility for a given picture situation. Photographer Brian Lanker once called me, slightly confounded, during a shoot on alternative energy pioneers. He was in Alaska photographing an innovative wheat farmer who also happened to raise buffalo. I was a reporter at the time, working in New York and pitching in.

Lanker had just gotten off the phone with Loengard and told me, “John’s idea is: ‘Why photograph this guy in the wheat field? Why not rent a Cessna and shoot him in the plane, upside down, over the field, while all these buffalo are down below.’ Well, how do you get the guy and the buffalo both in focus? Especially when he’s only got about six buffalo, which’ll appear as tiny specks unless you’re skimming right over the field. But now John’s got me thinking: a plane is surprising. And I sort of like the upside-down too.” So Lanker had me call around to find the going rate for renting prop-planes in Fairbanks.

“It was great because that one conversation opened the doors for me, perceptually,” recalled Lanker, in February 2011, a month before he lost his battle with pancreatic cancer. “I would never look at an assignment the same way again. I would always be looking for: what’s out there that we’re not thinking of? It was life-changing because you realized he was right. So often you approach an assignment and you put it in a box. But an assignment has no lid, no sides. It’s totally open. You go out and look at it fresh.

“John walked the walk, visually. I’d arrive somewhere and say, ‘There’s nothing to photograph here.’ But if Henri Cartier-Bresson or John Loengard were here, they’d have made a fabulous image. So I’ve got to go and find it. It’s there. And I know another thing: If you think it’s not there, you won’t find it.”

With Loengard-as-superego whispering in their ears, Life photographers would be fingering their shutter releases but continually asking themselves: What’s the story here? How does this picture fit into that story? What is this picture saying? Is the story line changing and should I therefore be changing my preconceived assumptions? What is this picture saying? What else should I be considering? How can I push this even further? Where’s the opener, the closer, the double-truck?

“He is very demanding, but I like that,” insists photographer Mary Ellen Mark [who would pass away in 2015]. “He demanded a certain kind of perfection. He wasn’t easily pleased. He had serious expectations when you worked for him and you had to meet them. You had to come through for him. Today, everything is formulized. It doesn’t have any soul to it. John loved images that had soul and were really about catching great moments. Look at Harry [Benson]’s work: he’d give Harry an impossible assignment and he’d come back with the goods. It was a challenge to work for John and I’ve always had enormous respect for him because he’s really a great photographer—he’s the real deal. His own photography is very iconic and technically beautiful. He knew what he was asking for.”

“John never told a photographer specific pictures to take on an assignment,” says Michael O’Brien. “He was the yogi who gave you one or two lines before going out that would help identify what you needed to do. I remember a feature story on [the Reverend] Jesse Jackson [who was then running for president]. And in one sentence, he reframed the whole story for me. He said, ‘If you’ve seen the picture before, don’t take it.’ He comment meant: show Jesse Jackson—a much-photographed personality—as you’ve never seen him.’

“You always knew where you stood with John. Compliments were very, very few. He was always straightforward. If you went in there [to his office] and he liked one or two pictures, you were on cloud nine. I remember spending three weeks riding on the outside of a tank in Germany, in February, doing a story on a U.S. Army tank sergeant. The film was sent to New York and developed [by the time I returned]. I arrived, hoping for a good word. I thought I’d done something magnificent. Instead, he turned to me with that unnerving gaze and said, ‘Let me put it this way, Michael. If the film had been lost in transit, we would not have lost a thing.’ He was one hundred percent direct. The point is: he never misled me, never padded the bad news.”

Loengard would go on to a career as an educator, an editor of distinguished volumes on photography, and a photo historian and critic. He is considered by many to be among the most astute writers about photography, respected for his enchantingly crisp, direct, and idiosyncratic style. He has also produced an invaluable archive of videotaped interviews with 43 photographers from the staff of Life, a collection that served as the basis of his compendium, Life Photographers: What They Saw.

And through it all—through the demise of the weekly picture magazine and the trusty Leica, the pocket light meter and the contact sheet—John Loengard continued making pictures.

All along, John Loengard recognized the coming transformation from traditional to digital photography. He understood its implications intellectually and viscerally. He was among the early industry leaders to foresee that the charmed world of silver and paper, given time, would fall away and be no more, replaced by an expanding universe of digits and pixels.

And as this new age dawned, he kept on making pictures: pictures of his fellow photographers; pictures of his fellow photo editors; pictures of their pictures—of photographers and archivists and heirs holding master photographers’ precious negatives.

His portraits of photographers, a project he began in earnest in 1989, was self-assigned at first. But as he started shooting, he now admits, “I realized it was a very dull topic. When it was me saying to photographers that I wanted to just hang around, the pictures lacked energy.” Soon, however, he received assignments to continue the endeavor and the pictures took on a new vitality. “When you shot on assignment, you arrive and it’s The New York Times Magazine or Life or People. You become a conduit. Your subjects get charged up. They do more. They really want to visually impress you a bit. They want to make sure you get something good to make them look good. You work off their energy.” The resulting portraits possess a vigor and a joie de vivre that mirror the life-affirming qualities of the practitioners depicted—and the art form they love.

As for Loengard’s studies of the guardians of famous photographic negatives, this body of work was completed in 1994, just as a small but increasingly influential cadre of photographers was becoming bullish about digital imaging. As soon as he finished shooting this series, Loengard says, “I realized that the negative had become an obsolete industrial artifact.”

He had become, in effect, an anthropologist, a lyric poet, a prospector in a sivler mine. Since the days of the first threshing machine, the first revolver, and the first telegraph, the medium of photography had long held the promise of permanence: a sliver of an instant could be captured on a flat surface, for all time. Recognizing this, Loengard had adopted the role of the alchemist-in-reverse: one who knew the secret process for turning silver into a simple object that enshrined a timeless moment.

But now the bedrock process upon which that permanence had been founded has itself evaporated like quicksilver. In its place, for better or for worse, we have a new process—one that tends to value the thrill of the merely instantaneous over the deeper meanings of the cherished instant. And yet on these pages, at least, we have a record, a picture story, a chronicle of a death foretold. As we regard John Loegard’s photographs, we find beauty, wonder, and revelation. And we can take solace in the notion that this new golden age of digital imagery has evolved, undeniably, from a past as bright as glistering silver.

David Friend