For our Beijing correspondent, Li Hu is a photographic discovery. A survivor of the Third Indochina War and the Cultural Revolution, he retired at the dawn of the 21st century to become a photographer. Below is the interview with CYJO.

Li Hu’s inauguration into the world of professional photography is a remarkable one. While photographers actively work to capture good stories, Li Hu’s work additionally captures the depth and substance behind his own personal history. Feelings of struggle, hard work, respect for the everyday individual and pride are some of the personal characteristics ingrained in his work.

Born 1955 in Zhen Zhou, Henan Province, he had overcome starvation in the 1960’s, survived the Cambodian-Vietnamese War in the1970’s, experienced the Cultural Revolution and proudly served as a Communist Party member working in the tax department, rising to the status of a high ranking official.

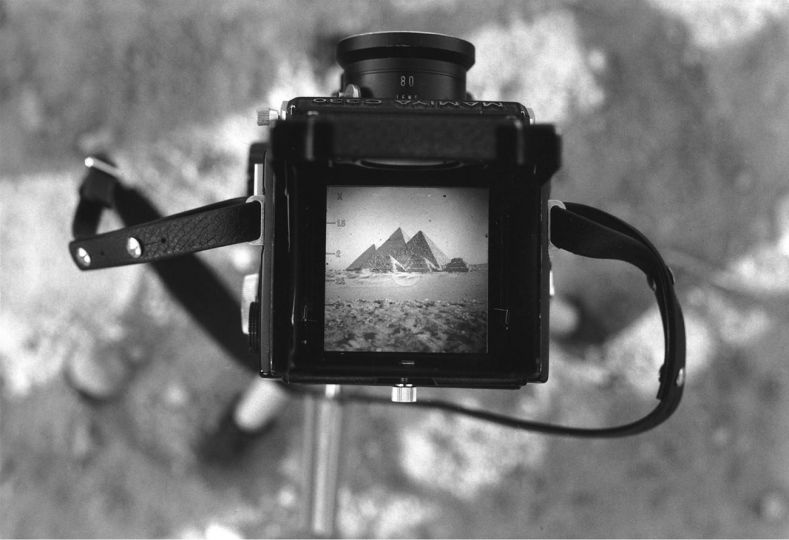

Given the opportunity to take an early retirement package due to government downsizing in the year 2000, Li Hu embarked on satisfying his childhood interest by becoming a professional photographer. He studied all things photographic, technique and works by major photographers, with all available international publications he could access. And he soon grew a liking to the international work of Richard Avedon, Arnold Newman and Eugene Atget among many others.

Because good photography education was not easy to find at that time, he self-taught and assigned homework for himself, where he experimented with different styles eventually crafting his own. There is a traditional Chinese saying, “The highest nail gets chopped off first.” While many strived to be part of a group, Li found his individual voice in photography that set him apart from the group.

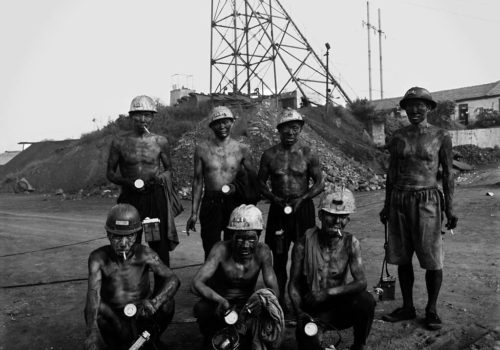

This voice eventually wove into his following works – Coal Miner, Happiness, Backwards-Backwards and End Bound Feet. Due to the extensive nature behind Li Hu and his work, this story will be divided into four parts, Li Hu’s history displaying his Coal Minor Project Photos, Coal Minor & Happiness with Li’s Happiness photos, Backwards-Backwards, and End Bound Feet.

How was it like growing up?

My generation passed through every hard step of China’s development, the 3-year Disaster, the Cultural Revolution and the Open Door Policy of 1979. The policy was the first of its kind where Deng Xiaoping said we should focus on the economy, not just the political aspects, but on expanding and growing as a whole.

Before 1973, it was not easy due to the dearth in food. The 3-Year Disaster, 1960-1963, was one of the hardest times growing up because the food was very limited. China also had some problems with Russia.

I was starving when I was little where we shared limited food with a big family. We would get a small pan, boil some water, and put vinegar and salt in it. And we’d drink that convincing ourselves it was soup. I remember eating potatoes several different ways. The leaves in the trees didn’t taste good, but we ate it. The grass, we ate as a kind of vegetable as well.

My youngest brother had it harder because my mother was too malnourished to produce milk. This meant that my aunt’s one sheep needed to be fed to produce milk. It was the sheep’s milk that helped my younger brother to survive. We looked like malnourished African children with a swelled belly that you would see in magazines at one point.

My second major experience was with the Cultural Revolution, which started when I was 10 years old. I was sent to a small county, Huai Bin to work in the countryside for 6 months. My parents did not go. Only the children were sent.

More people focused on learning the philosophies and ways of life of the rural farmer than on their own studies. We embarked on government-mandated trips to the countryside where we learned from the soldiers, the peasants and the workers, 3 important social classes at that time. Even if you weren’t the best student, you could obtain a high-ranking position before you finished high school.

High school graduates were also sent to work in the countryside for 4 years. At the age of 18, I was sent to the south to Xinian, Henan Province. We did the same kind of work as the local farmers, planting peanuts and beans and doing everyday chores.

After my 4-year commitment, I became a soldier and served in the army for the next 10 years. I went into the Vietnam War in 1979. At that time, Vietnam wanted to take Cambodia so they started a war in Cambodia. But China being allies with both countries helped to protect Cambodia from being overtaken. I was there for just one month, but within that month was able to witness the destructiveness and reality behind war. The value of life and enjoying life became crystal clear.

By the end of 1986 the army was reduced by 1 million soldiers. Since I was not needed in the army, I was moved to the tax department on January 2nd, 1987. During the next 14 years, I went from working as a basic secretary to an official and eventually was promoted to a high-ranking official.

In 2000, the government structure changed. There were too many leaders in the government, and they asked some in high positions to retire earlier so the younger staff can assume some positions. Knowing that I wanted to explore other interests in my life, especially photography, I took the offer. My same salary and benefits were maintained, but the work was given for the younger people to do.

When did you become interested in photography?

Since I was in middle school, I liked photography. I liked drawing and taking pictures when I was a teenager. I didn’t have money to buy a camera but one of my classmate’s parents had one. And I always asked to borrow his camera to take some pictures.

After the war, all survivors in the army received a stipend/award of 110 RMB (11.7 Euros), I used this to purchase my first camera for 80 RMB (8.5 Euros) to get a camera, Haiou (Bird Flying over the Sea) camera.

This interview was conducted and edited by CYJO