Spanish artist and researcher, Ixone Sádaba (1977, Bilbao) has been working for around twenty years. She has an art degree from the University of the Basque Country, she has been exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and at the MOCCA in Toronto. It is today at the Azkuna Zentroa cultural and art center in Bilbao that her images of the abandoned Lemoiz nuclear power plant are projected, life-size Escala 1:1 (1:1 scale). Encounter.

Jean-Jacques Ader: Did you choose to work on the Lemoiz nuclear power plant and why?

Ixone Sádaba: Absolutely. It started during confinement, when our movements were limited. I was on a motorcycle ride with a friend, we were passing this road near the power plant, I saw buildings overgrown with vegetation, and, looking at the political-social history of the construction of the power plant, suddenly the whole past came back to me. The history of its construction dates from the Franco era, in 1972, which planned the installation of four power plants, Lemoiz was abandoned in 1984, after the political transition with a lot of social unrest. A second reading, from my point of view, concerns the Anthropocene, collapse, environmental problems etc. I found it incredible that no one had done research on this.

Why present the rendering in the exhibition at real scale (1:1)?

IS: Among the themes I intended to address, the scale of representation was essential. When you look at the plant from above, it appears very large but never as impressive as when you are right in front of it. Also, the architecture of these buildings is from another era, a time and an imperialist spirit. Of course, scale is important in photography. The image projections therefore start from the ground to give visitors the most realistic vision possible; here at the art center, there are very large rooms that allow that.

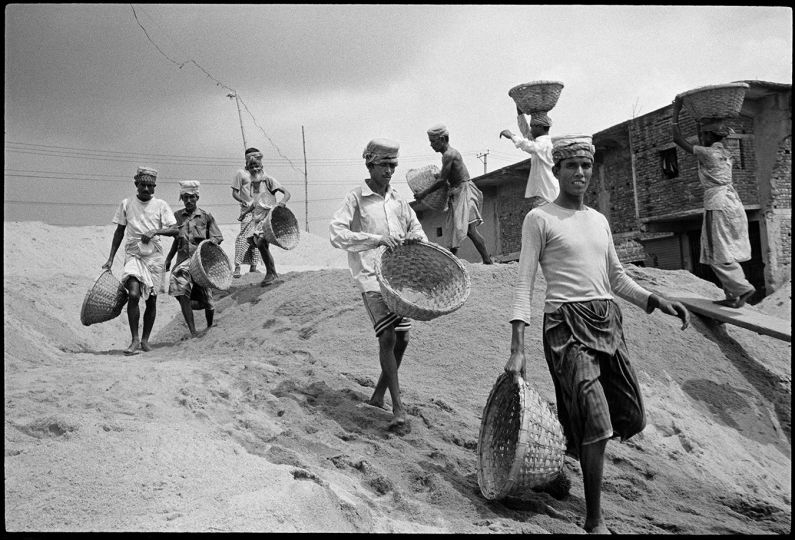

You took some photos in color (presented on stands in portfolios) but the large projections are in black and white

IS: I don’t have any particular preferences in photography; I am even quite critical of the medium when I use it, but I tell myself that if I see in color I must photograph in color. On the other hand, in this project I think that black and white facilitates the dialogue between the infrastructure of the buildings and the surrounding vegetation.

How did you go about shooting in subjective vision, to scale, and reproducing it on different screens?

IS: Oh, it was a nightmare… (laughs) I had to define a frame with my camera at a 1:1 scale by aiming at a specific element in the image, from a specific point of view; and then move laterally, counting my steps, with the distance markers materialized by ropes, to be able to encompass the buildings in two or five shots, depending on the case.

I read in your bio that you deal with “political scenarios” like this unfinished nuclear power plant project, but is it the view that is political or the subject?

IS: I think it’s both, right? The place where the power plant is located has never been contaminated, for example, but there is social and political contamination, and this is why the site is closed and still secure, fifty later. And when you look at this site or the images on the site, you look at it from your well-defined place, you also choose your point of view.

You seem to pay attention as much to the form of representation as to the content of your works.

IS: Yes, it’s a reflection on my work but also on photography. This Escala 1:1 exhibition has two subjects: the nuclear power plant of course, and the other is photography, or its history at least. Because photography holds a special place in representing the idea of progress. For example nuclear energy, of which we know the terrible risks, and the fact that it is not a viable solution. Photography contributed to this idea that progress can be beneficial.

Does being a photographer mean being at the right distance?

IS: I think we have to enter the subject. When we look at a photo we don’t see a camera, but there is no photography without a camera. I consider it a performance to take pictures; here, it was a bit David against Goliath because of the immense size of the buildings, all this concrete, isolated in the middle of nowhere, I had to play with the light or rather it played with me, I had to come back numerous times, more than twenty times, for hours, it was very physical. Also, rather than choosing the right distance from your subject I believe you have to dive into it.

Is it complicated to be faithful to reality?

IS: Of course. Photography cannot be objective, it necessarily comes from a point of view. This is why it is important to remember, even if we do not see the camera in the images, that it is constitutive of photography, so everything is subjective. The distance, the scale, the size, the colors. I actually believe that the main point of this exhibition is that reporting on a 1:1 scale is impossible, we cannot be perfectly faithful to reality.

Jean-Jacques Ader

ESCALA 1:1, exhibition by Ixone Sádaba at Azkuna Zentroa Alhóndiga in Bilbao (Biscay, Spain) from February 6 to April 27, 2025.

Exhibition curator: Carles Guerra (teacher and art critic)

Information: https://www.azkunazentroa.eus/en/

https://www.ixonesadaba.com/