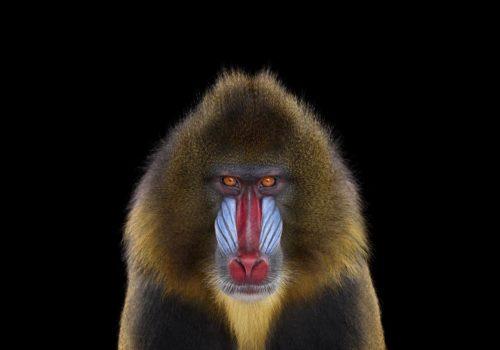

American photographer Brad Wilson has been developing the Affinity since 2010. The photographer travels with his mobile studio to zoos and wildlife sanctuaries to capture the wildlife living there.

He is always in search of what he calls his Holy Grail: to capture the direct gaze of his model, to create that unsettling face-to-face encounter that makes us question the distance that separates us. Brad Wilson agreed to answer a few questions for The Eye of Photography.

Portraiture seems to have always been your favorite genre. What drew you to portrait photography, and what keeps you interested?

I find my subjects (both human and animal) to be complex and mysterious, so it is always a unique and interesting challenge to reveal and capture something meaningful and insightful during each session. For me this is the artistic journey–one that illuminates not just what is in front of the camera, but what is behind the camera as well. The more I learn about my subjects the more I learn about myself.

What is more difficult and more rewarding about photographing animals rather than people?

Most of the animals I photograph are effectively wild. Although they have been habituated to people to some degree, they are not domesticated or trained the way a dog might be. I cannot communicate with them or direct them the way I would a human subject, so I have to wait patiently for them to settle and show me some uncommon moment, some brief, but authentic window into their world. Even during the best shoots, this window is only open for a few seconds at most. That is the challenge and the reward.

Your photographs of animals borrow from the codes of portrait photography rather than those of wildlife photography. What is your intention in replacing humans with animals?

Once art moved beyond the religious iconography of predominantly church-based commissions, portraits began to feature a variety of individuals from society at large. You might see laborers in a field or hunters on horseback for example, but only wealthy art patrons or aristocrats were depicted without context. They were deemed special or unique enough to be pictured alone. I brought this historical convention to my portraits of animals to challenge our collective notion of human exceptionalism, and help define a new paradigm to recognize the significant consciousness and deep emotional lives of our fellow creatures.

Your photographs raise many questions about the circumstances in which they were taken: how did you gain access to the animals? How far away are you from them? What equipment do you use? Who is with you during these sessions? Can you tell us a bit more?

The hardest part in the beginning of the project was gaining access. Animal sanctuaries or zoos do not want to let just any photographer in to work with the wildlife they are caring for and protecting. At first I paid significant fees (in the form of donations) to produce my photo shoots, and soon I had created a number of nice portraits that I could show people as clear examples of what I was trying to accomplish. After this access was much easier, but still expensive.

In general, I set up a full photo studio where the animals live or somewhere nearby. I use a variety of commercial photography lights and high-resolution medium-format digital camera equipment to capture the best quality image possible. And, of course, a very large black cloth background. On each shoot there are a number of animal handlers (anywhere from 2-5) and my photo assistants. In general, I am very close to each animal – usually a few feet away. There is a feeling of connection and intimacy with this closeness that I am trying to capture in the final image.

Your work also raises the issue of animal welfare. How do you ensure that the sessions are not too stressful for the animals?

Every photoshoot I do proceeds at the pace of the wildlife I am working with. Nothing is forced. When the animal is done, the shoot is over–whether that is 5 minutes or 3 hours. The well-trained sanctuary or zoo workers know their animals and are in a good position to judge the situation, so I trust them to determine when it is time to stop. Of course, the animals can let you know in very direct ways also. If a lion or tiger lays down to take a nap, the day is finished.

You said, “I would describe each session as a kind of meditation in the midst of organized chaos.” What do you mean?

I am usually surrounded by multiple handlers and assistants–all focused on the wildlife, not me. The animals are not caged or restrained, so they are free to explore and they often wander off, or turn over equipment or come right up to the camera. A lot of rather chaotic activity is happening around me so I have to ignore it, relax and focus on one thing: finding my photograph. I let go of the strong emotions generated by being in such close proximity to these magnificent creatures so it feels like a meditative state.

Do you have an ideal photo in mind at the start of each session, and do you try to guide the animal towards it?

As humans, we connect with others and the world around us through sight (more than any of the other senses). Making direct eye contact with another person or animal offers us a strong feeling of connection. With this in mind, I try to get each of my subjects to look straight into the camera. This is an extremely difficult task since animals often perceive direct eye contact as a challenge or a threat, so they only engage in this behavior under specific circumstances. It is hard to “guide” the wildlife I work with to do this, but if I am lucky, I might get one or two images over the course of the photoshoot.

Looking at your photographs, it’s clear that people’s fascination with animals is as strong today as it was when our Palaeolithic ancestors drew animals on cave walls. Why do you think this is?

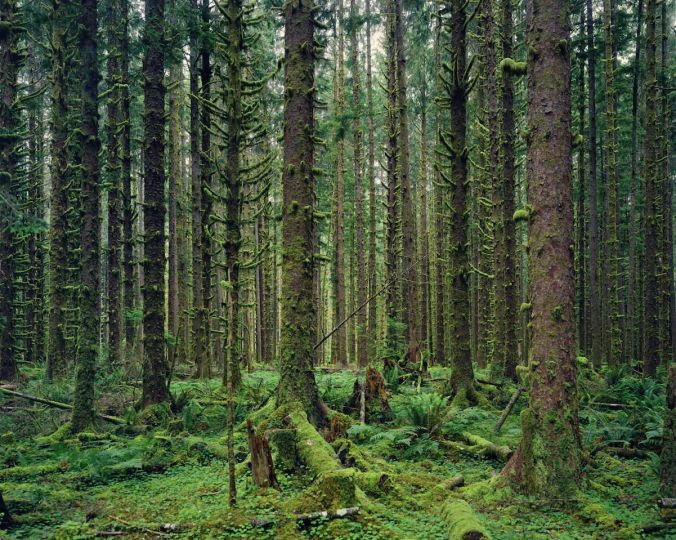

It is funny that you mention cave walls. My newest series of photographs entitled Artifacts (soon to be released) references those walls, our early homo sapien ancestors and the first art they created. We evolved alongside animal species for millions of years, and until about 12,000 years ago (when we started farming and building permanent settlements), we lived exactly as they did, inhabiting the same natural environments. Our history is a shared history. This connects us to wildlife in a deep and profound way that is part genetic memory and part kinship.

Dan Flores points out in his foreword to your book that our reaction to animals is both instinctive and cultural. Has this project changed the way you look at animals?

I certainly saw animals differently after interacting with them in such a close and direct way. There is a profound intelligence and presence that resonated with me on a primal and emotional level – something that elevates each creature to a sort of “equal but different” stature. This is much less apparent and powerful when you are seeing wildlife from a distance for very brief periods of time, which, unfortunately, is how most people experience animals. Instead of knowing or understanding them in any real way, we create our own cultural mythologies around their existence, and then treat them accordingly.

Do you think your photographs can change the way people look at them? What thoughts do you hope to provoke through your work?

I do hope my photographs can, in some small way, change the way people look at animals. Through the process of creating this series of work, I discovered a world that we, as humans, have largely abandoned – a place of instinct, intuition, and present moment awareness – a fully natural world, distinct from the increasingly urbanized and digitized landscape that surrounds us. In the midst of our modern human civilization with all its technological complexities, animals still remain stark symbols of a simpler life and a wilderness lost. Perhaps these images can stand as a testament to this other fading world, and remind us, despite the pronounced feeling of isolation that too often characterizes our contemporary existence, that we are not alone, we are not separate – we are part of a beautifully rich and interconnected diversity of life.

For more information:

View Brad Wilson’s biography, video interview and portfolio on the Artistics website: