By Sally Martin Katz

I am delighted to present the work of Arthur Tress, an American photographer born in Brooklyn in 1940, who resides in San Francisco. He received a BFA from Bard College and attended film school in Paris. His work is included in major collections such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA, LACMA, and the Centre Pompidou. After working as a documentary and ethnographic photographer, Tress embraced a more personal, theatrical approach to photography, combining elements of real life with fantasy. Aligning himself with the genre of “magic realism,” he stages tableaux that visualize dreams or scenes from his imagination. Influenced by shamanism and the work of artists like Duane Michals, Giorgio de Chirico, and graphic novelist Lynd Ward, his photographs take on a mystical and surrealist dimension.

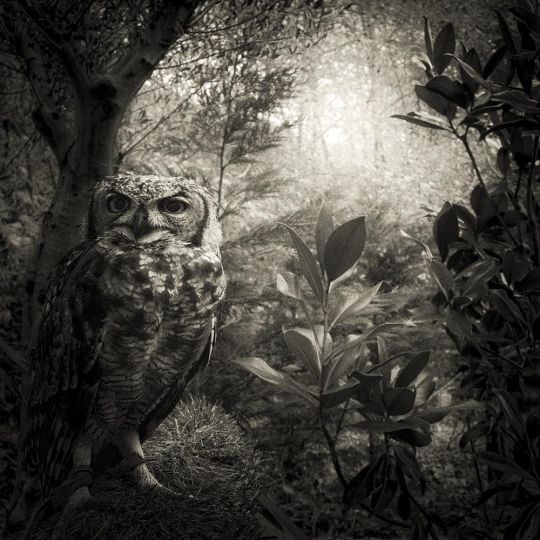

The 96 gelatin silver prints presented today are from Tress’s 1974 shadow series, which depicts the artist’s own shadow as the mythical protagonist of a shamanistic “vision quest.” Organized as a sequential visual narrative, the series is divided into thirteen sections that portray the shadow’s escape from confinement and its travels through urban and natural environments before experiencing a transformation and finally a state of illumination. Although Tress uses his own body to act out these dream voyages, these are not self-portraits; he creates an anonymous character physically separated from his own skin that takes on a life of its own.

To make the series, Tress would hold a wide-angle lens camera in one hand and gesture with the other, often while wearing or holding props. Working across different locations within New York, Arles, Nice, Cannes, and San Juan, he wandered around these cities, performing a sort of pantomime. He tried to capture the sense of amazement and wonder of discovering the city that this archetypal shadow character feels. There are almost no other people in these photographs—they are about his solo journey and the idea of a rite of passage, a learning experience.

The story, or “novel in photographs,” conveys a progression over time. The first chapter, titled “The Prisoner,” is about inserting the body into barred spaces and structures. By playing with the position of his camera and the directionality of his shadow, he has visually imprisoned the figure. In this way, he is able to place himself visually in a space he does not physically occupy. Tress constructs a fiction by deliberately framing the shadow within his compositions. He can fabricate a story that is not actually happening in reality. The titles, which dramatize the scenes, serve to imply this storyline or guide the viewer to make certain associations or interpretations. In the last photograph in this sequence, we see the shadow getting out, being released from confinement. The following chapters depict the shadow out wandering, discovering different landscapes like the ocean or the dry salt flats in the Camargue.

Tress uses visual tricks where the shadow is broken, or split across different surfaces, and the wide-angle lens allows him to give a dreamlike quality to the images. They challenge our understanding of perspective and dimensionality in a photograph. A shadow is flat and horizontal, but here it appears vertical, as if standing up out of the background plane. The shadow skews our sense of proportion, monumentalizing or dwarfing the figure it represents. Through his geometric compositions, rich black and white tones, and emphasis on chiaroscuro, Tress evokes a sense of drama, suspense, and mystery. He experiments with photographing at different times of day to vary the length of his shadow and create different personalities of this shadow alter ego. Inspired by the idea of spiritual pilgrimage, Tress illustrates how after wandering across landscapes, the shadow reaches a state of transcendence, as seen through imagery of ladders of light and upward-moving shapes.

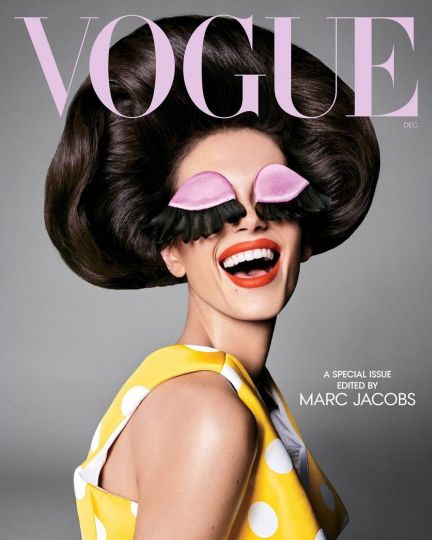

Throughout the series, Tress employs props to aid his storytelling and add a fantastical element to the different scenarios he enacts and the characters he embodies. In the “Labyrinth” chapter, he appears as the Minotaur, and later, using a poncho and a crown, he transforms his shadow into a bat-like creature looking down over the cityscape. In the “Transformations” section, he suggests a metamorphosis of the body’s shadow into something inhuman, like a three-headed lamppost, or into another entity, melding into the environment as he merges the shadow of a tree with his own. In a sort of self-referential way, Tress concludes the vision quest with his shadow reaching enlightenment, becoming a sort of lightbulb figure, or planetary god, who comes back to the world through his lens, which the artist holds in his hand like a crystal ball.

Sally Martin Katz

Curatorial Assistant, Photography

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The Shadow series is featured in the current group exhibition:

Don’t! Photography and the Art of Mistakes

curated by Clement Cheroux, Matthew Kluk, and Sally Martin Katz

Until December 1, 2019

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

151 3rd St,

San Francisco, CA 94103