On the occasion of Art Paris, which will take place from April 4th to 7th at the Grand Palais Éphémère, Galerie XII is dedicating its booth to Sophie Zénon, who joined them at the end of 2023.

Our correspondent Zoé Isle de Beauchaine met the French artist at her studio, where her diverse practice involves several skills to explore how a plant can bear witness to history.

You are exhibiting at Art Paris the final installment of a cycle titled “Rémanences,” in which you address the memory of war landscapes through the prism of vegetation. How did this project come about?

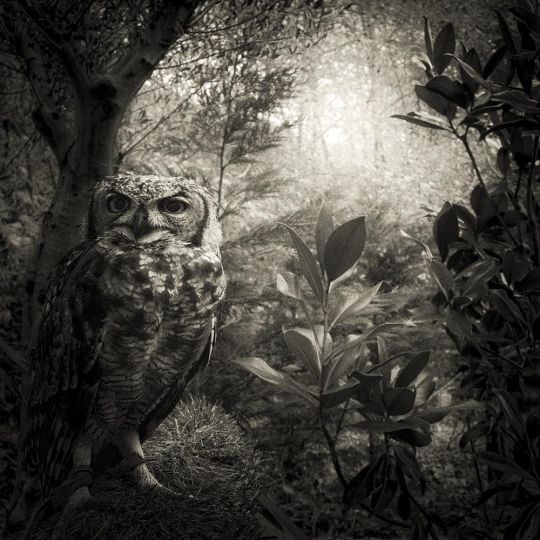

The “Rémanences” cycle began in 2013 with an artist’s book titled “Verdun, ses ruines glorieuses,” a plastic interpretation of the “broken faces” created from postcards of German and French soldiers, engravings, and excerpts from the book “La Bataille d’Occident” (Actes Sud, 2012) by the writer Éric Vuillard. I specifically chose passages related to fragmented and shattered bodies, to the devastated landscape. My book ends with this phrase borrowed from the author: “a battlefield is a landscape like any other,” opening up to the question of war landscapes and their representation. This introduced me to a universe and led me to question the beauty of the forests in the Grand Est region, sites of terrible conflicts. Is it possible to allow oneself to find these forests beautiful despite all the tragic history that has unfolded there? Building new narratives with the dead, establishing a connection that takes us elsewhere, and in this case, for me, towards the living, is a common thread in my approach. Because even though death is very present in my work, the question of the living is at the heart of my reflections: how to live after, how to live with? And how, through and with photography, to account for it?

These questions drive the different installments of “Rémanences,” whether it’s Verdun mentioned earlier, “Pour vivre ici” created on a site of the First World War in Alsace, or “Frondaisons,” which brings together photographs of a Breton forest that hosted the Maquis de Plésidy-Saint Connan in 1944. What about “L’Herbe aux Yeux Bleus“?

In the Vosges in 2017, at the Hartmannswillerkopf site, I discovered the work of the botanist François Vernier on obsidional plants, those propagated by armies during periods of conflict. François Vernier discovered twenty-one plants inadvertently introduced to Lorraine from the Napoleonic wars to the Second World War: by the Cossacks, the Russians, the Bavarians, the Germans, the Americans, and also by French troops coming from other regions. These seeds were found in soldiers’ uniforms, under their shoes; they dispersed and colonized the landscapes of the region. Among them, the “Herbe aux Yeux Bleus” (or Mountain Blue-eyed Grass), a tiny and delicate flower that blooms at a specific time of day, was introduced by American troops during the First World War, contained in the hay intended for horses.

How did you approach the history of these plants?

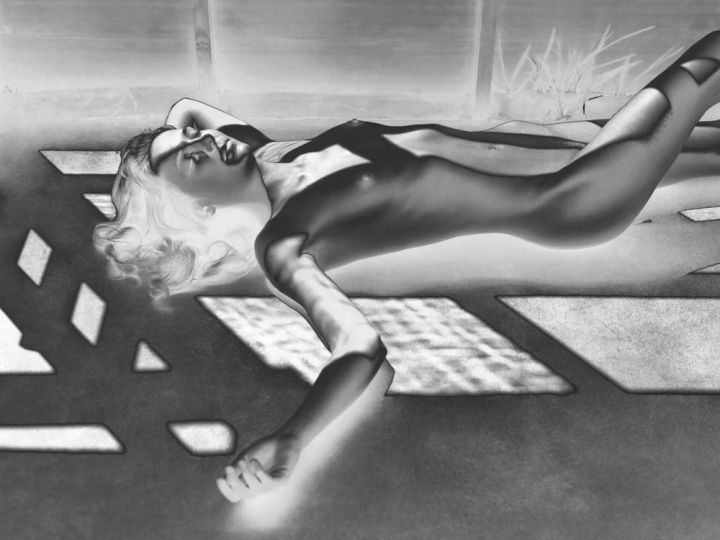

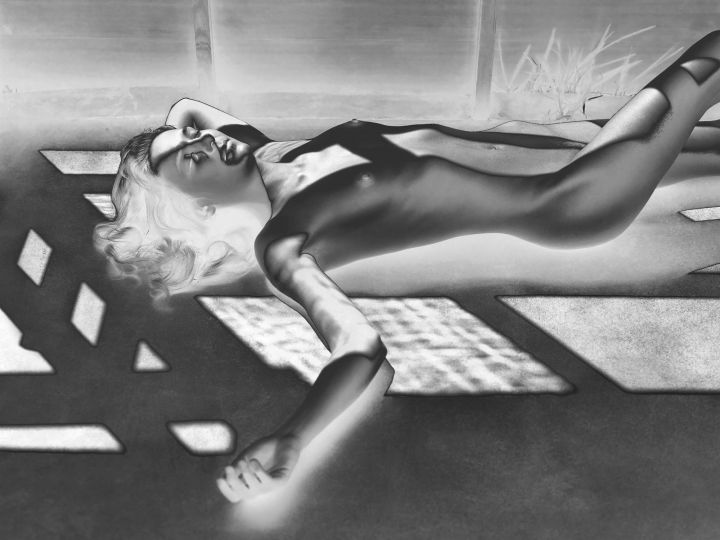

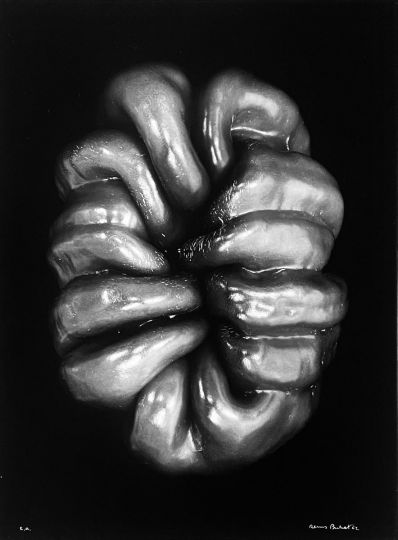

These plants are witnesses of witnesses; they grew on the ashes of the dead. I positioned myself as an intermediary; I put myself at their service because they are the ones with a story to tell us. From there, the idea of making photograms was born, which are the direct imprint of the plants. I wanted an organic work, rooted in materiality. Whereas photography only reveals the surface of things, the photogram will account for the density of a stem or the concavity of a leaf. I also wanted there to be no intermediary between the plant and the viewer. I worked with the printer Diamantino Quintas for the large formats, whom I have known for over twenty years. We followed an experimental path; I wanted to go beyond the rendering of a “classic” photogram (only black and white) to create materials, colors, enigmatic landscapes from which smoke or battlefield illusions would emerge.

The exhibition will also feature several artist’s books combining these plants with history.

I drew inspiration from the codes of the herbarium to imagine artist’s books made from iconographic archives of “L’Album de la Guerre” (1914-1919), published in 1923 by the newspaper “L’Illustration.” For each plant, I designed an album in which, like a palimpsest, I made the plants converse with the archives (“Herbarium florum obsidionalium“). For the “Bunias Orientalis,” for example, I mounted a photograph of this flower printed on extremely thin Japanese paper on an archive depicting a battle scene, all enhanced with pigments, wax, and earth.

In addition to obsidional plants, your exhibition addresses the history of so-called “mitraille” trees.

These trees are witnesses to the great battles of history. They grew back while keeping shrapnel or shell fragments inside them. They are recognized by the scars visible on their trunks. I made photographs on a 1:1 scale of these scars, printed in charcoal to transcend our initial vision of the bark (“Stigmates“). In the Art Paris exhibition, they are juxtaposed with orotones (photographic prints on glass plates with gold leaf), giving a complete view of the tree, an ancient process allowing me to render these precious and delicate trees (“Duramen“). The ensemble is presented in the form of a mosaic mixing deep blacks with touches of golden light. From these same trees, I imagined delicate and fragile paper sculptures, made from imprints of their bark on Chinese paper usually used in calligraphy. Then came the modeling, made possible by delicately weaving the paper with brass or copper threads (“Vegetal Topography“), created with the complicity of textile designer Charlotte Kaufmann. I wanted to move away from the primary register of the bark to create an imaginary landscape, an animal skin, a delicate envelope. I then went further and, inspired by a soldier’s coat from 1914, I cut out my imprints and sewed them with small stitches into a “Manteau de Neige,” evoking a ghostly presence. All this work revolves around the notions of macrocosm and microcosm: from the tree trunk to the 1:1 detail of the scar, to the imprint of the bark itself, a form of abstraction that ultimately becomes very incarnate.

Would you say that the “L’Herbe aux Yeux Bleus” installment marks an evolution in your practice?

With each of my projects, the challenge is to avoid repetition and to find the plastic form that is most in line with what I want to express. This involves photography, hybridizations, but also other mediums. This last installment of “Rémanences” is a large woven canvas from which I pulled many threads, and each thread has helped enrich another. With “L’Herbe aux Yeux Bleus,” it’s the first time I’ve gone so far in experimentation.

More information