Harold Feinstein cannot be reduced to a single series. Nevertheless, for this native of Coney Island, this ‘land without shadows’ remains first and foremost the field of his photographic practice and above all the perfect illustration of a certain vision of American society.

In partnership with The Harold Feinstein Photography Trust. This exhibition takes part of the Rencontres d’Arles program as part of the Grand Arles Express manifestation.

Born in 1931, Harold Feinstein’s sole ambition was to become a photographer. His biography is well documented. It is known that he joined the Photo League at the age of 17 and, in Sid Grossman’s entourage, he learned to empathise with the common folk of New York, those excluded from ‘prosperity’.

In this post-war America, despite it not being a good idea to show sympathy for this group of resolutely committed artists, Harold Feinstein saw no other possible path for his photographic practice than to remain as close as possible to the senses and the living. This is why Coney Island is more than a theme. For sixty years, the photographer regularly returns to this subject, to the origin of things. The perfect combination of a biography and a community.

Coney Island, an area of Brooklyn and a former island, the westernmost tip of Long Island, has seen the development of activities linked to the major waterfront since the beginning of the 20th century. For New Yorkers, Coney Island offers the possibility of escaping the heavy summer heat.

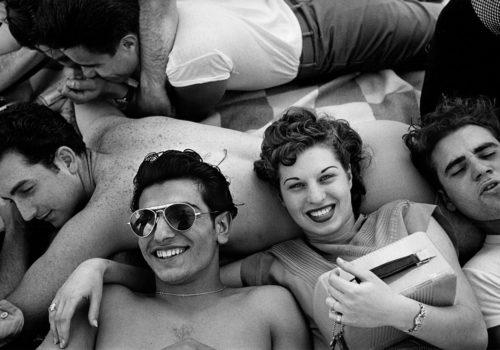

Until the 1950s, the use of the beach was inseparable from the use of the many amusement parks. It is home to the largest concentration of attractions in the United States. Several million visitors a year flock to The Wonder Wheel, The Cyclone or The Parachute Jump. New Yorkers of all backgrounds, whether Italian, Jewish, Puerto Rican or Black, attend the Mermaid Parade, have their palms read and leave the fairgrounds delighted and satisfied. This is not a catalogue of entertainment, nor is it a collection of portraits or a restrained melancholia.

The set of images produced over time forms the backdrop of a work that is characterised by its desire to write a series of short stories from day to day. The narrative dimension remains the fundamental contribution of photography that eliminates all negative tension in favour of a collective dimension, of an experience shared by an entire population. Behaviour hardly differs from one class to another, from one community to another.

The beach, the Riegelmann promenade and the attractions form a common way of being. The mode of appropriation of the place is collective and unifying. Harold Feinstein’s Coney Island is a photographic transcription of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue: ‘Music should express people’s thoughts and aspirations, as well as their era. I am a man without tradition, my people

are Americans and my time is today. I have the modest claim to contribute to the great American songbook. That’s all.’ There is no ‘pure’ contemplation in these images, it is above all an ethical disposition, an aesthetic of the ordinary. There is nothing important in these series of small moments. Nevertheless, it is these moments, these gestures and stances, these strange encounters, that structure and ensure the continuity of a commu- nity. All of this ultimately composes an ensemble, a great songbook in the midst of the upheavals of American society, with the Great Depression, the exacerbation of racial tensions, McCarthyism, etc.

In contrast to the images of Diane Arbus, there is no anxiety here; everyone is together and in communion around the same practices. These simple events are the foundations of the nation as Harold Feinstein envisions them, a fusion of races, communities and age groups. ‘What’s remarkable and nourishing about Harold’s black and white work is that he addresses a really gritty, stressful, difficult environment – an archetypal city like

New York, which many people have shown as dark, dangerous, gloomy, isolated, inhumane – and consistently finds in it the moments of charm, pleasure, human tenderness, generosity – even the spiritual – that is there.’

It was then, in 1952, that the young Harold Feinstein, drafted by the army, found himself in the American expeditionary force in Korea. Denied a position as an official photographer, he served his time in uniform like any other conscript: ‘I was assigned to the infantry. In retrospect, this was a great boon, because I was able to carry my camera everywhere and simply capture the day-to-day life of a draftee and not the official handshakes and medal ceremonies I would’ve been required to shoot as an official photographer.’

His photography documents the stages that accompany the life of each draftee from conscription to military operations in an original way. ‘I was 21 in 1952 when I got called up to go to war. I had recently been married. I remember being in a room at Camp Kilmer with hundreds of other young men around my age, stripping down for the physical, walking through the inoculation “assembly line” and then getting transported to Fort Dix for sixteen weeks of basic training before being shipped to Korea.’

The format that Harold Feinstein experiments with in the Korean narrative brings together the every day and the art of the blues. He invents a narrative full of shades of grey and delicate contrasts. The slow rhythm and muted tones all provide extreme consistency to a series made up of sensitive appropriation and abandonment of the subject to the photo- grapher’s desire.

Upon his return to the United States, Harold Feinstein established himself in the Jazz Loft, New York, where he met the musicians Hall Overton and Dick Cary. This was the period in which he began his collaboration with the Blue Note Records label. Crucially, he also met W. Eugene Smith, with whom he collaborated on the layout of the Pittsburgh Project. His career took off once again when he exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1954 and at the Limelight Gallery in 1955.

It is this vision of the world, of photography committed to the benefit of a united humanity, that the photographer seeks to convey. The other passion of Harold Feinstein is teaching. He obtained his first teaching fellowship at the age of 29 at the Annenberg School for Communication (Philadelphia), followed by a post at the Maryland Institute College of Art (Baltimore), then at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art and finally at the New York School of Visual Arts. His approach is in some ways close to ‘street photography’. His images taken in the underground or the streets of New York, captured with all their details, form a singular perspective. Narrative worlds unfold yet the work remains a unified whole. Harold Feinstein introduces a singular tension into the narrative aesthetic between accidents and mirror effects; the work is an entity that imposes itself as an immediate sentiment, held together by its style rather than its subject matter.

François Cheval

Centre de la photographie de Mougins

43 rue de l’Église

06250 Mougins

www.cpmougins.com