Curated by Carolina Ponce de León — formerly of the Luis Ángel Arango Library in Bogota, El Museo del Barrio in New York, Galería de la Raza in San Francisco, and the Ministry of Culture in Colombia — the exhibition devoted to Colombia deconstructs social, historical, and environmental identity of the country.

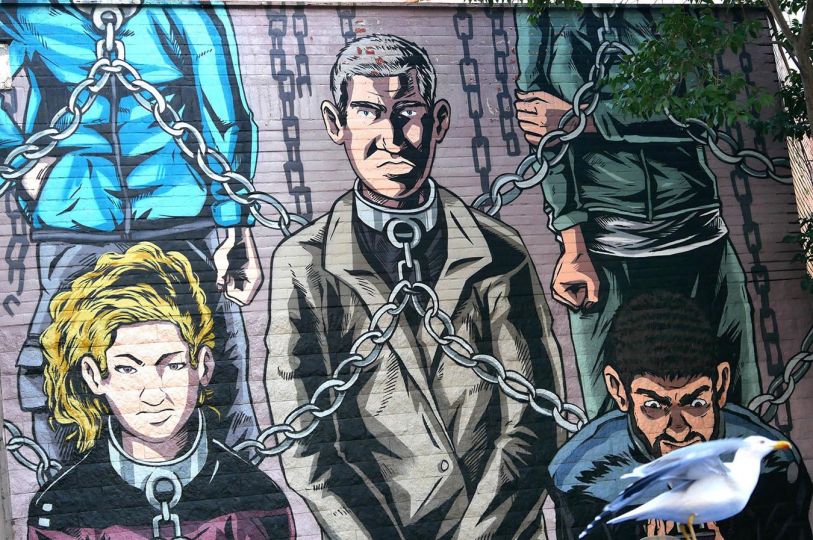

It is not surprising that the first topic it broaches is the armed conflict, “which has only perpetuated the culture of political violence in Colombia over the past six decades,” as we learn from the Introduction. The work of the young artist Andres Orjuela (b. 1985), exploring the topic through the visual archives of a Bogota tabloid, is well worth a detour.

Through annotations and recontextualization, Orjuela reappropriates countless images of prisons, killings, arrests, and other instances of violence, attacking a certain form of revisionism pertaining to that chapter in Colombian history. Some captions on the backs of photos are thus corrected, sometimes crudely, by simply crossing out and overwriting the original without worrying about the credibility of the added information. This is true of an image of two men standing before sacks filled with marijuana, where the new caption plainly indicates, “coke traffickers,” even while cannabis leaves are visibly poking through the burlap. This game of alteration of photographic prints is far from innocent in a country where the identity of murder victims has been falsified to enrich the assassins. This was the case in the famous scandal involving doctored prints: it came to light in late 2008 that members of the Colombian national army had been assassinating innocent civilians and passing them off as guerrilla fighters killed in combat, in order to bolster the results of their combat brigades. Orjuela’s work thus tries to point out the discrepancies in the political discourse as it relates to history and deconstruct lies.

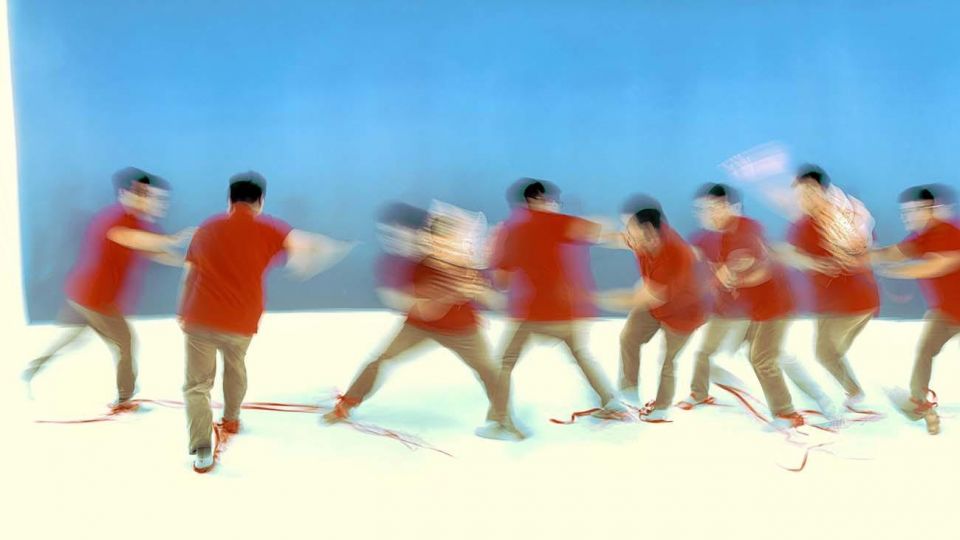

Similarly, Liliana Angulo (b. 1974) attacks another form of revisionism. Her work restores the Afro community, suffering from widespread scorn and contempt, to its rightful place in Colombian identity. Using sometimes caustic humor, Angulo’s practice revolves around the notion of negritude, dissecting stereotypes and their social and political implications. “I work with words, their different meanings and connotations in Spanish, as well the origins of the resulting expressions,” she explains as a way of introducing her approach.

In Negro utópico (2001), Angulo reprises the Afro aesthetic of the 1960s and 70s, namely the voluminous hairdos typical of the disco era. She dresses up her model in the fabric of the same pattern as the background, arms her with household tools, and has her mimic postures expressing cheerfulness and spontaneity. Angulo deployed the same approach in Mambo Negrita (2006), in which a woman wears a boubou and a hair wrap tied in a top knot over her forehead, both made of the same polka dot fabric as the backdrop. Borrowing an aesthetic dear to studio photographers in Africa, with poses reenacting situations generally associated with white people, Angulo subverts the negative stereotypes attached to the Afro-Colombian community.

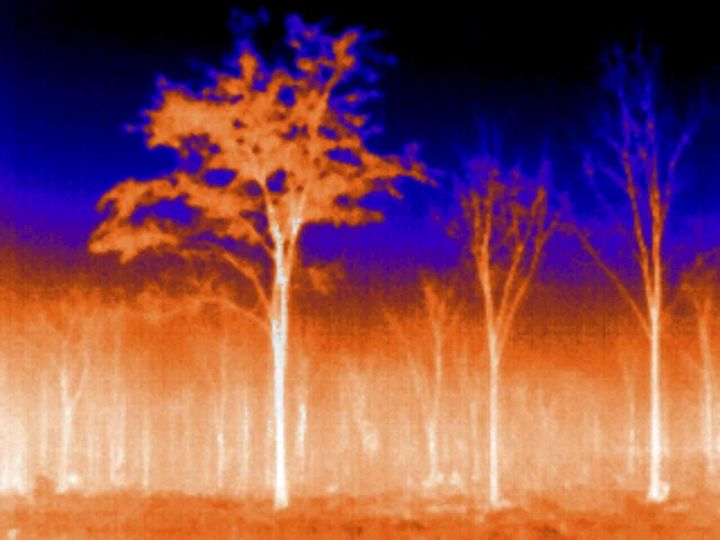

Lastly, the exhibition emphasizes nature, from the early scientific expeditions through the present, foregrounding the country’s wealth in terms of biodiversity. This may be shown with incisive humor, as in the inventory of artificial plants by Alberto Baraya (1968).

Laurence Cornet

Laurence Cornet is a journalist specializing in photography and an independent exhibition curator. She divides her time between Paris and New York.

La Vuelta

Festival des Rencontres de la Photographie d’Arles 2017

July 3 to September 24, 2017

Arles, France