On the occasion of Gilles Aymard’s retrospective at the Municipal Archives of Lyon, which are held from November 8th, 2024, to February 8th, 2025, we had a conversation with Laurent Baridon, professor at Lyon 2 University and art historian specializing in 19th-century architecture, who was curator of the exhibition.

What led you to present the work of Gilles Aymard?

There are several things. First, a familiarity with Mourad Laangry (Exhibition Manager at the Municipal Archives of Lyon), with whom I have worked on several occasions in relation to the archives. Then he invited me to join a meeting with Gilles Aymard, and as we talked, I became increasingly involved, then Mourad asked me to take on the role of curator and also contribute to the exhibition catalog.

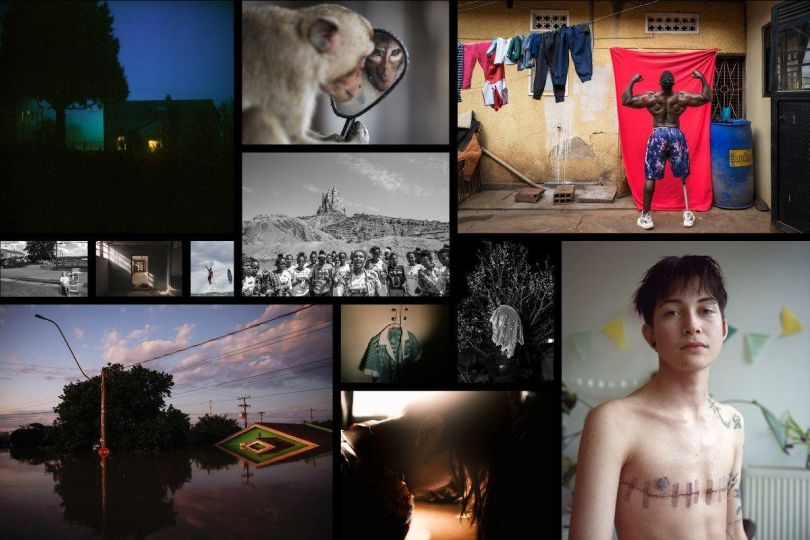

We had many discussions with Gilles about the focus of this retrospective exhibition. He showed us hundreds upon hundreds of photographs, and the question was, how do we blend all of this together? Eventually, we found a guiding thread to convey the diversity of his work, as well as his unique way of photographing people in spaces and capturing their professions with great empathy. The exhibition is constructed around architecture, but it also reflects how Gilles is able to bring architecture to life for those who observe it. Most people don’t necessarily think to appreciate architecture this way, not just the grand monuments, but also in daily life.

The challenge was to show how architecture is made alive by the people who live within it, and how it’s essential to convey that life within architecture through photography. We tried to highlight this in the exhibition. For the catalog, I wrote most of the texts with Nathalie Pintus, who is also an art historian and has specifically studied 19th-century architectural photography. Mourad was interested in having this dual perspective and situating architectural photography within a broader historical context.

Are you particularly familiar with photography?

Not specifically with photography itself, but with the representation of architecture more generally, especially the ways it intersects with texts to create coherent narratives. I am very interested in illustration overall, and that naturally includes architectural illustration.

In your opinion, how has photography served architecture?

Initially, I think photography took over the role of drawing. The illustration within texts and the rise of illustrated books in all categories became significant in the first half of the 19th century. A classic example is Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to the 16th Century in 1858. It was the first truly ambitious, historical, and theoretical book with in-text illustrations. At this point, photography clearly took on the mission of replacing drawings, though it was not yet easy to reproduce or incorporate into books. Techniques didn’t immediately allow that.

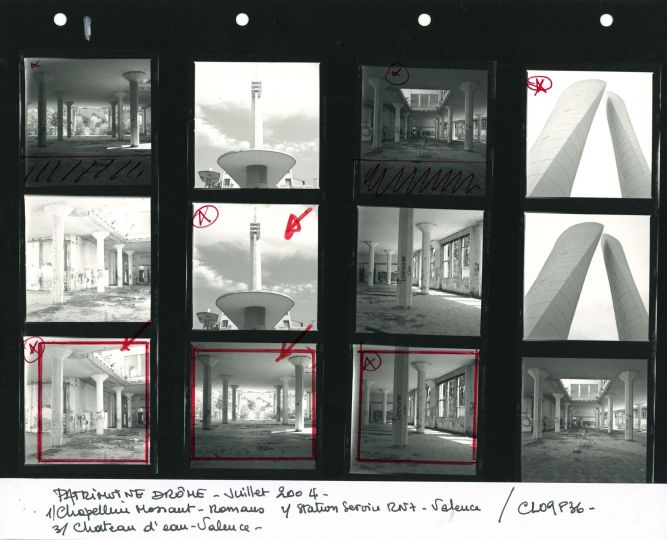

But this tradition of architectural drawing persisted, particularly with the specific goal of showcasing national heritage. Heritage was a crucial driver in the development of architectural photography. At the same time, lists were being compiled to prioritize which buildings should be preserved or funded. So there’s a dual influence here: the illustrated book and the longstanding tradition of architectural imagery, which evolved with the advent of photographic tools.

There are, of course, several types of architectural photography. Earlier today, I was showing my students Le Corbusier’s photos of the Acropolis in Athens from his 1911 trip. He had a small portable camera, which he used to take documentary shots, yet some of them are still highly aesthetic.

There’s also a very artistic style of architectural photography. I’m thinking of Thomas Ruff, for example, or architectural firms like Herzog & de Meuron, who merge aesthetic appeal with architectural imagery.

And then, as Gilles himself pointed out, there’s commercial architectural photography, which produces images for architects and developers a commercial product. Gilles’ talent lies in developing a more artistic approach alongside this. He captures the formal aspects, understanding volumes and plays of light and shadow, but he also gives empathy to the buildings he photographs. Just as one would create a portrait of a person, Gilles doesn’t merely see a building that needs to be showcased. He seeks to highlight it with an intimate understanding of what the architect intended.

His talent also lies in perceiving the finer details, embodying the idea that, as Mies van der Rohe said, “God is in the details.” Architecture, no matter how grand, is fundamentally about details and finishing touches. Gilles understands this, and he brings the volumes to life, showing both the strengths and tensions, always with great subtlety. One can’t help but think of the photographers associated with the New Objectivity movement, particularly those linked to the Bauhaus, with their powerful compositions of balconies seen from below, and strong geometric contrasts. Photography is an integral part of the aesthetic definition of architectural objects—it’s not just a commentary or explanation. It’s truly part of it, even though, of course, the architectural object existed before it is photographed; the aesthetic intentions remain the same.

More information