In late 1982, Andy Warhol and a small entourage were invited to Hong Kong by Alfred Siu, a young industrialist who had commissioned portraits of Prince Charles and Princess Diana for I Club, a huge new disco he was opening on the island. Upon arrival, Siu surprised the party by informing them he had been successful in arranging a VIP trip to Beijing, the Forbidden City and the Great Wall. Andy Warhol was to visit China for the first and only time. We caught up with the man who captured the trip, Warhol’s close friend and personal photographer Christopher Makos, ahead of his show here in Shanghai this month.

“It was really a disco trip to Hong Kong,” Christopher Makos says, “Alfred Siu had commissioned Andy for the Prince Charles and Lady Di portraits to decorate his new club in Hong Kong, and then surprised us with the Beijing trip. We all were actually surprised. And excited to see mainland China.”

Described by Warhol as the “most modern photographer in America,” Makos was at the time working on Warhol’s Interview magazine. Also on the trip were Fred Hughes, Warhol’s flamboyant Texan manager, Hughes’s girlfriend, English aristocrat Natasha Grenfell and documentary maker Lee Caplin with a small film crew.

“Andy was the sort of front man of the band,” Makos has said of the party. “And we were the backup singers.”

Yet while Warhol was at the height of his fame in his home country, the 54-year-old artist was virtually unknown in the People’s Republic of China, which had only recently emerged from almost total isolation from the outside world and instigated the policy of Reform and Opening Up.

“For some strange reason, some Chinese did recognize Andy, much to our surprise,” says Makos. But for the most part the very recognizable artist only stood out in a crowd “because he looked so unusual, not because he was the guy who painted those portraits of Mao.”

Yes,with the Mao portraits. In 1972, the year Nixon went to China following ping-pong diplomacy, Warhol had reached outside Hollywood and America for his next superstar: Mao Zedong. Stripping the iconic image of its propaganda context, he rendered it ironically fashionable in the West with his use of wide, colorful brushstrokes and hand drawn lines. Whether intended or not, the works mirrored political efforts to give China a friendly face in the eyes of Americans.

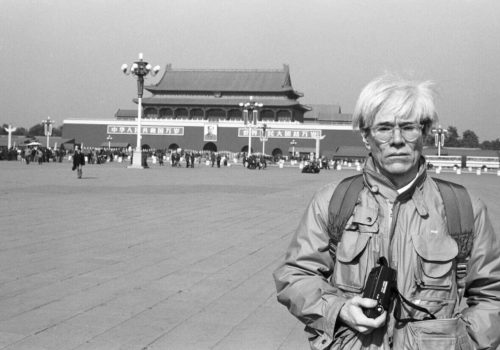

A decade on and Makos photographed Warhol posing in front of the original in Tiananmen Square. “Andy actually thought the real Mao portrait was better than his, and really loved the original,” says Makos. “We were all fascinated with the real portrait.”

“Gee it’s big,” Warhol said himself at the time. “Yeah, I painted Mao about four hundred times. I used to see how many I could do in a day.”

It is this notion of replication and uniformity that makes the concept of Warhol in China resonate. “It was a Warholian experience,” Makos later reflected on the trip. “Here’s the guy that, you know, did the Campbell’s soup can — he was all about the multiplicity of things, and here was a whole lifestyle based on that idea.

“I loved the sense of isolation, especially in a fashion sense,” Makos says. “It was just a sea of these people all in crisp navy blue suits. They looked so chic. To me, the new group that was experimenting with Western-style dress just looked so un-cool. Because they were so isolated, they really had no sense of how to dress, so it was intuitive. Sometimes a hit, most of the times a miss.”

It is a sentiment that was echoed by Warhol, who even had a copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao, better known as The Little Red Book. “I love his book,” he said. “I read it all the time.

I like the simple thoughts. “I like this better than our culture. It’s simpler,” he said. “I love all the blue clothes. Everyone wearing blue. I like to wear the same thing every day. If I were a dress designer I’d design one dress over and over.”

(Ironically, Warhol wore the same outfit every day while in China, even sleeping in his clothes. But for hygiene rather than aesthetic reasons – he complained that the Peking Hotel, where he and Makos were staying, was full of cockroaches.)

If Warhol approved of the Mao era, they were less positive about what he represented. By 1982, younger artists were beginning to be influenced by Western art, but later that year the Chinese government initiated an Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, with ‘spiritual pollution’ being defined by as “things that are obscene, barbarous or reactionary; vulgar taste in artistic performances; efforts to seek personal gain and indulgence in individualism, anarchism, and liberalism.” Contemporary art was decreed “bourgeois,” and several exhibitions were banned.

In fact, the only artist Warhol met during his visit was the traditionalist Chang Ku-Nien, a master calligrapher and landscape painter, who professed not to know much about Western art, but had seen a picture of Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe in a foreign magazine.

In an artistic exchange, Chang inscribed ‘long life,’ in calligraphy and gave it to Warhol, while Warhol drew a large dollar sign in magic marker and wished Chang “good fortune.” When Makos later teased Warhol for making such a crude gesture, and of always having money on his mind, Warhol retorted: “I have mind on my money – it’s different, kid.”

While Warhol professed preference for the simplicity and conformity of China, the absence of the usual ubiquitous cultural icons and lifestyle of convenience that his works reflected left him somewhat uneasy. “Andy asked ‘Where are the McDonalds?’ when we were in Beijing,” says Makos, “And when we were out at the Great Wall, he asked, ‘Where is the escalator?’”

As Ai Wei Wei notes in an essay in the opening of Makos’ Andy Warhol China 1982, a photographic book chronicling the excursion: “He never once believed that a world without McDonalds could be sympathetic or kind; as in a child’s eyes, a place without McDonalds could never be good – no matter what else it had.”

Changes were already underway though, and as Warhol himself predicted – on first being told there was no McDonald’s in Beijing, “Oh, but they will,” was his rejoinder.

Things moved on artistically as well as culturally, and just as he was known as the ‘Pope of Pop’ in America, a case can be made for Warhol as the godfather of contemporary Chinese art. His simple aesthetic and replication of ever-present imagery has influenced those in the Middle Kingdom fusing pop and Cultural Revolution–era propaganda to create a style referred to as ‘political pop,’ while some here have become so successful they have begun art ‘factories’ of their own, just as the master had.

As such, Warhol’s 1982 trip to China is a brief yet fascinating look at the artist in a culture that both influenced him, and was to be influenced by him.

April 2013, www.thatsmags.com

Warhol in China by Makos

June 14-18, 2013

The Wine Gallery

41 Hengshan Lu

Shanghai

China