Seventeen years ago, photographer Adam Jahiel embarked on a mission to document buckaroo life. Thousands of images later, he says he’s still discovering the secrets of one of America’s most unique cultures.

Story by Ryan Thomas Bell

Photographs by Adam Jahiel

The term “daybreak” bears a loose definition on a buckaroo outfit in the Great Basin. For the cook, it comes around 3 a.m., when he rises to fire the stove and make breakfast. Next to rise is the horse wrangler, who saddles in the dark and rides into the black desert to jingle the cavvy. While he’s away, the rest of the crew stirs. No reveille of trumpets sounds, just the hiss of propane lanterns as they’re lit one by one.

The cowboys bide their time, waiting for the lanterns’ heat to warm the air inside the canvas tent walls. Finally, they dress and emerge, carrying lanterns in one hand and cigarettes in the other. Gathered in the cook tent, the crew is somber, few of them looking up from cups of coffee long enough to make small talk. Metal forks plow eggs across plastic plates as they wait for the sound of the wrangler and the saddle herd’s arrival.

The men pay little attention to photographer Adam Jahiel, who waits on the periphery.

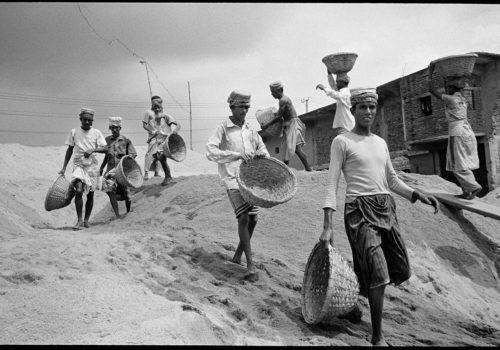

Armed with a medium-format camera, Jahiel has created a body of work that documents nearly two decades of Great Basin ranching. He calls it “The Last Cowboy Project.” Every summer since 1989, Jahiel has traveled parts of Idaho, Nevada and Oregon, capturing images of the region’s cowboys, landscapes and historic ranches.

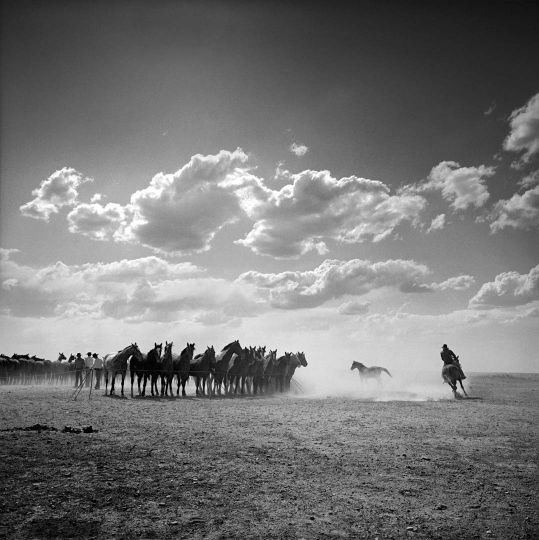

Today, his photographs number in the thousands and include portraits of buckaroos, horse roundups, summer brandings and tent camps in the middle of wide-open country. The pictures evoke a feeling of permanence for the buckaroo culture, seemingly rooting it to the soil like sagebrush.

Cookhouse Inspiration

The Last Cowboy Project was born on a summer day in 1989, when Jahiel — then working for The Sacramento Bee — was sent to a ranch on the California-Nevada border to shoot photographs of the famed rodeo bull Skoal’s Pacific Bell.

“After we drove around the ranch shooting photos of the bull, we ended up back at the kitchen for a cup of coffee,” Jahiel remembers. “I looked around inside the cookhouse and saw how stark and pared-down everything was. There was the obligatory table with red-and-white checkerboard tablecloth and a conglomeration of ketchup, mustard, Tabasco and toothpicks. The walls were whitewashed wood, and there was absolutely nothing fancy about it. In the other room, there was a couch that had been destined for the dump years before. Cowboy gear was everywhere and someone had drawn a crude bucking-horse illustration that hung on the wall.”

Jahiel felt like he’d landed in a picture by Walker Evans, one of his photographer heroes. During the Great Depression, Evans documented 1930s rural America for the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

“There was something incredibly compelling about those FSA images,” Jahiel says. “They’re technically perfect, and the subject matter had real historical importance. It wasn’t just eye candy. They were historical documents.”

Jahiel asked the ranch owners for permission to return and shoot photographs on his own time. They agreed and provided him with a letter giving him access to the many ranches they owned across Nevada.

“The first ranch where I spent significant time was the IL in northern Nevada,” Jahiel remembers. “I arrived and began taking photographs, even though I really didn’t know what I was doing. I kept my eyes open and mouth shut. I didn’t want to miss anything and just tried to stay out of the way as much as possible.

“After about 10 days of shooting, I thanked the cow boss, told him I’d gotten the pictures I needed and that I’d be leaving that morning. All he said was, ‘Okay,’ then rode off on his horse to go back to work.”

The departure felt anticlimactic, and as Jahiel packed up his gear, he thought about how difficult it might be to enter the closed-off world of the Great Basin buckaroo. Then, the cow boss rode back to Jahiel and said, “If you want to do any more shooting on any other ranches around here, you can use me as a reference.”

Jahiel had a foot inside the door.

“As a rule, these guys are poker-faced and men of few words,” Jahiel observes. “I had no idea where I stood with them. So, when the cow boss said that, it was one of the greatest honors I’ve ever received. That set everything in motion.”

Wall Art

As a photographer, Jahiel is drawn to moments that go beyond shots worthy of Marlboro ads. He divides his Last Cowboy images into two categories: “hero” photographs and “documentary” shots.

His hero photographs are those that command attention and make for popular wall art. One such shot, one Jahiel calls Rancho Grande, depicts a rearing horse looming larger than life over a cowboy whose face is obscured by the shadow of the corral fence. The photo is packed with action and dramatic contrasts between clouds, shadows and light. Jahiel sees in it a statement about man’s relationship to the natural world.

Jahiel’s documentary photographs are taken from everyday life and give the viewer an intimate feel for buckaroo culture. They’re less likely to hang above a fireplace, but Jahiel appreciates such images for their “soul and grit.

“So much of the material I’m interested in takes place before and after work,” he says. “Guys get up and do their thing, take off for the day’s work, and when they get back, they work on their saddles, read, fix gear, snooze and tell stories. Really, it’s a miracle such a style of life exists in this day and age.”

Naptime is an unassuming Jahiel documentary photograph that makes up in story-telling what it lacks in action. Taken during an afternoon branding on Nevada’s TS Ranch, Jahiel remembers how the photograph unfolded.

“There were horrendous numbers of cattle to brand, and it was one of these days that just seem to go on and on. Everyone was dead tired,” he explains. “In the background of the picture you see a couple of guys working. There’s an older kid full of energy and spinning around with his arms and legs in motion. Then, there are a couple guys standing around checking stuff out. One man, sitting with his back to you, has a big triangle-shaped sweat stain across his shirt. And, in the foreground, there’s a young kid, maybe 6 years old, who’s crashed out, asleep. He has an old man’s hat on, his face is dirty, and he clearly couldn’t take it anymore.

“I saw the scene and realized how many incredible storylines were being told. It’s such a great one, but it isn’t a flashy photograph that anybody will ever buy to hang on a wall.”

Cowboy Portraits

Any photographer who hopes to take a portrait of the notoriously stone-faced buckaroo has his work cut out for him. One of Jahiel’s greatest challenges has been to blend into the woodwork and put his subjects at ease so they act naturally in front of the camera. The key to his success has been returning to the same ranches through the years, eventually earning the cowboys’ trust.

“Sticking with something for more than 15 years will get you a different feel than if you just go once and leave,” Jahiel observes. “I like returning to visit these guys, and they open up to me as a result.”

Jahiel discovered that when he arrived at an unfamiliar ranch, a reference from a cowboy down the road was worth gold.

“From one ranch to the next, it’s such a small world,” he says. “The more time you spend, the more guys you meet, and the more you fit in and learn the ropes. You learn when to disappear and when to reappear.”

A portrait photographer’s goal is to catch a subject in a moment when his nature is unaffected by the presence of a camera. Sometimes, Jahiel has succeeded by catching his subjects unaware. Portrait photographs like Riley Cleaver have an intimate quality, putting the viewer alongside the cowboys in a cook tent or bunkhouse. For other photographs, Jahiel used a technique he learned working with portrait photographer Arnold Newman, whose images of people like President John F. Kennedy and the composer Igor Stravinsky are world-famous.

“He was a crusty old guy,” jahiel remembers of the late Newman. “He’d fuss around with his lights for what seemed like forever. The people he was photographing were excited to get their picture taken, but they’d nearly fall asleep by the time Arnold was ready.”

“I realized he was doing it on purpose. As he bored his subjects to death, he’d scope them out to observe their nature. Little by little, as you relax, you become more real.

“I’m always watching people, how they sit, their body language. When I told these cowboys I was going to take a picture, immediately they’d stiffen up. So, I would guide them back to sitting the way they were when they were acting naturally.”

At Shutter Speed

Jahiel is a cowboy and horseman at heart. Horses graze outside the window of his Wyoming studio, and working gear — ropes and bits — intermingle with his endless collection of photographic equipment It’s understandable, then, why Jahiel draws a parallel between the professions of buckaroo and photographer. He sees in both a need for skilled expertise and “gut” instincts, whether it’s throwing a difficult loop or snapping a technically perfect picture.

“Any kind of art form — writing, photography, roping, saddlemaking — requires so many great things to come together,” says Jahiel.

That revelation came to him during the summer of 2006, when he visited a cow camp on Nevada’s Spanish Ranch. One day, he overheard the cowboys discussing a ranch roping they’d attended in Elko, Nevada.

“They described one particular cowboy’s rope throw in an incredible way, as if they’d watched it in slow motion,” he recalls. “Listening to them, you could almost feel the position of the cowboy’s hand and wrist, how the rope slowly uncoiled, the shape of the wave it made as it went through the air, and the way it landed so the calf stepped into it.”

Jahiel recognized in their conversation a concept he was used to discussing as a photography teacher, the idea of a “slice of life.” In theory, Jahiel thinks of a photograph as a frozen moment in time that enables the viewer to see details that aren’t visible with the naked eye. The cowboys, in effect, were discussing a “slice of life” taken during the Eiko ranch rodeo, a moment printed to memory and visible without the need of a camera.

Of all the pictures in The Last Cowboy collection, Roping a Cloud stands out as Jahiel’s masterpiece. He took it one predawn morning at a cow camp on the IL Ranch. The wrangler had corralled the saddle herd, and the outfit’s top roper was methodically roping out the day’s mounts.

“The scene was pregnant with possibilities,” Jahiel remembers. “There are a lot of patterns that occur from the repetition of cowboy work, like roping, branding and herding. You know what’s going to happen, so a photographer can have a leg up on things and be prepared. I recognized the pattern of the wrangler as he’d step forward, throw the rope and catch horse after horse.”

The sun was not yet up, and there was next to no light available. Jahiel looked through the viewfinder and saw only black. Nonetheless, he adjusted the camera’s settings to capture as much light as possible, training the lens on the center of the rope corral. He relied on timing alone to take photo after photo, not knowing what image he was capturing. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later, when Jahiel returned to his Wyoming studio and developed his film, that he found out whether or not he was successful.

“There was one picture that I could see from a mile away was ‘the one,'” Jahiel recalls. “The rope happened to be encircling a solitary cloud in the background sky. Did I sit there and wait for the wrangler’s rope to go around the cloud? Of course not. I didn’t even realize the cloud was there. That’s the magic of photog- raphy. You prepare yourself the best you can, then trust the luck factor.”

The Anonymous Buckaroo

In a deserted bunkhouse on southeastern Oregon’s ZX Ranch, Jahiel stumbled across an artifact of cowboy archeology, a buckaroo’s journal. The author’s entries were short, sometimes cryptic and often comical. One thing about the diary, though, was articularly intriguing: It was written graffiti-like on the walls of the bunkhouse in a barely legible handwritten cursive, as if the buckaroo were a prison inmate marking time on his cell wall.

The entries began at ceiling height, with straight-lined sentences that descended into columnar disarray at waist-level. He recorded livestock movements, wrote about the events of daily life, and concluded each entry with a comment about the weather.

10-6 Rode in lower reservoir.

110 pairs.

Rained all afternoon. – Cold.

10-7 Bosses late for work.

Being the loyal, dedicated,

hardworking crew, we went on with work.

Shipped 80 pair. For Little

Coyote moved 204 cows

and 22 bulls from B.

Coyote to Upper Res. Mike

took sick with Yellow

Belly. Clayton’s birthday.

– Cold, windy.

10-8 Gathered Thompson

into Big Coyote. 91 cows

4 bulls. SOBs. The whole

bunch was. – Nice.

Like the musings of that disappeared cowboy in the abandoned bunkhouse, Jahiel has observed firsthand that the ranching culture of the Great Basin is fading. During his nearly two decades in the region, he’s witnessed cowboys getting older, retiring and passing away. Younger cowboys have become scarce, drawn away from the ranchhand life by economic, political and social pressures. The ranches themselves are even disappearing, sold to owners who don’t require cow camps or the buckaroos who tend them.

“The ‘disappearing cowboy’ is a huge cliche,” Jahiel admits. “However, no matter how much you think you’re living in the ‘old days,’ you’re not. That part of the country [the Great Basin] is a slice of the past that’s practically disappeared. Those cowboys live in camps, tents and teepees. They have camp cooks, maybe a radio, even if they can’t pick up a signal. From morning to night, they’re camped out somewhere in the desert, miles from civilization. Because of that, they have to rely on what bare necessities they have.

“Visually, it’s fascinating to see a bunch of teepees out there in the middle of nowhere, the makeshift corrals they put up and the ancient buildings left behind that mark the old locations of former camps.”

It’s understandable why Jahiel considers a deserted, graffiti-walled bunkhouse an archeological treasure. Walls get painted over or, worse, come down altogether when the building crumbles. Likewise, the Great Basin buckaroo is himself anything but a permanent fixture. In the end, windblown sagebrush will outlast him. But, through Jahiel’s work, he’s guaranteed a spot in history and some form of cowboy afterlife.

Text reprinted with permission from Ryan Thomas Bell – Author