The following is a “manifesto” we drafted last fall while formulating the initiative called “A Day Without News?,” which launches this Friday.

David Friend, Aidan Sullivan, Sara Solfanelli

Overview

On Friday, February 22, 2013, we inaugurate an annual day of remembrance, solidarity, and action called “A Day Without News?”.

That day, most notably, is the first anniversary of the loss of journalists Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik, who were killed while covering the ongoing conflict in Syria.

“A Day Without News?” attempts to raise awareness of the dangers faced every day to record the truth. We are asking consumers of news to imagine a journalistic worst-case scenario: a world in which correspondents are everywhere absent, unable to bring voice to the voiceless.

The goals of “A Day Without News?”:

–to remind people that harming journalists in a war zone is considered a war crime

–to increase public awareness about the fact that we get our news

from intrepid journalists at risk in conflict zones

–to support the successful prosecution of perpetrators of war crimes against journalists

–to gain support from within the media community for those

organizations that are dedicated to these issues

The Rationale

Imagine a war without photographs. Imagine a conflict zone where no correspondent ever dared venture. Imagine a humanitarian crisis that came and went without eliciting a flicker of video, not a second of audio, not a single news story, not a lone blogpost. Imagine war crimes without witness—atrocities whose perpetrators were held forever unaccountable.

This, of course, is not some dystopian vision. This, in fact, was how war was waged across the dark millennia. Men took up arms; the mightiest seized power; combatants and innocents perished; and history, fitfully, moved on. Except for the stories passed along through the generations by tribal elders, reconstructions rendered by historians, or accounts related by first- or second-hand observers, such was the steady state governing every clash, every famine, every calamity—before journalism came along in the 17th century.

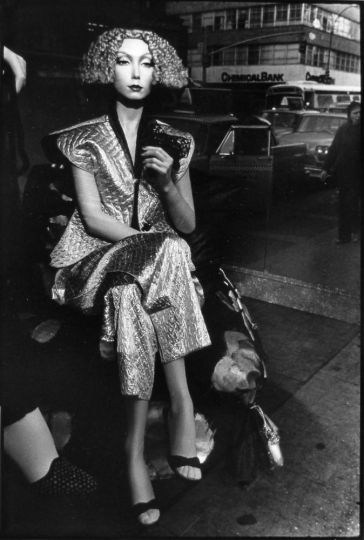

Today, however, the world is a wired one. When conflict breaks out, the theater of war is flooded with men and women—professionals, amateurs, and concerned citizens caught in the crossfire—armed with notepads and cameras, laptops and tablets, microphones and mobile phones. And instead of our having to wait days or weeks for their dispatches, coverage is virtually instantaneous, reaching those “on the outside” who might be in a position to intercede or resolve or, at the very least, attempt to understand.

But not for long.

Today, those who cover conflict are more at risk than at any time in the history of war reporting. More and more frequently, journalists are singled out for abduction, acts of brutality, or murder; they are imprisoned or held against their will; they are censored, besieged with threats and harassment, or expelled from their home country; they are subjected to psychological abuse or sexual violence. In many instances they are victimized because of their profession—by combatants who, in some instances, are intent on silencing them as witnesses. Indeed on 22 February 2012, in one of the most alarming such incidents in recent memory, correspondent Marie Colvin and photographer Remi Ochlik, while on assignment in Syria, were slain by government troops who, according to some observers, had specifically bombarded the press center where the journalists had been stationed.

“There is no question that it has become much more dangerous to be a journalist,” Paul Steiger recently remarked. The former chairman of the board of the Committee to Protect Journalists [http://cpj.org/], Steiger was journalist Daniel Pearl’s editor at The Wall Street Journal in 2002 when Pearl was kidnapped and subsequently killed in grisly fashion by his militant captors in Pakistan. “In the past,” he has observed, “if you had a press pass … it tended to protect you. Now it can be a magnet for murder.”

Indeed, the world over, virtually no violent crime against a journalist is ever prosecuted. And this lack of retribution or consequence may very well contribute to the continued cycle of violence.

How, then, to help ensure the safety of those in the field? How to raise consciousness about journalists’ collective predicament in an ever-more-perilous working environment? How to engender respect for the job of the correspondent covering conflict? How to attach a sense of indispensability—in the mind of the reader, viewer, listener, or browser’s—toward the sources of their supply of hard news, investigative journalism, and humanitarian reportage? In sum, how to get the word out that news gatherers matter—and in certain instances are actually paying with their own lives in their attempts to enlighten their audience?

Thus, we launch the initiative “A Day Without News?”

For more information and to lend your support, visit ou website.

David Friend