Human intelligence at the Helm: 50 ans dans l’œil de Libé by Françoise Denoyelle

First the Arles exhibition, at the Abbey of Montmajour, an austere but fresh place, conducive to the shock that the alignment of so many exceptional photographs provides.

Exceptional, the word is not overused and is simply explained. For 50 years, photographers have selected images in their reportages, directors of photography, editors have chosen one or two to feel in for the thirty that appear every day. A fairly substantial sum of photographs accumulated throughout the 52 weeks or so (there were a few daily interruptions). In the end, it’s called archives, kept in the suburbs in 280 boxes and 120 others at the newspaper’s headquarters, to which are added the hundreds of thousands of captures saved in servers fed by the uninterrupted flow of new images arriving every day. All that remains is to select the quintessence to make a book and then subtract two-thirds to install an exhibition, i.e. the supreme editing: the selection of icons that make history.

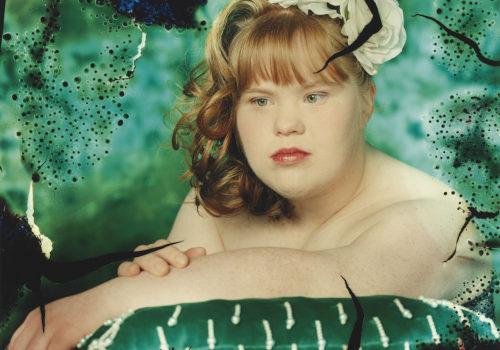

The icons still have to be there. If I rely on my experience of press funds: L’Illustration, Le journal, Paris-Soir, France-Soir (National Library of France, National Archives of France, Historical Library of the City of Paris) there are some nuggets and something to delight in, as in the Excelsior collection, the first daily to really take an interest in photography (L’Équipe/Roger-Viollet), but not to such an extent. At Liberation they are there in profusion. Images of Francine Bajande, Laurent Van der Stockt, Didier Lefèvre, Patrick Artinian, John Vink, Martine Franck, William Klein, Jean-François Campos, Jérôme Bonnet, Claudine Doury, James Natchwey, Antoine d’Agata, Bertrand Desprez…The list is covering the entire history of photoreportage of the period, unfolding the swings and moods of photography. Masterpieces on all levels.

The exhibition offers them published, displayed on the front page of Liberation as the common thread of the events and actors who have marked this half-century. Then come the majestic prints whose large format allows you to scrutinize the details. The images of armed conflicts, urban guerrillas, social struggles, presidential campaigns where the candidate puts on a show, social conflicts, urban violence, but also the decisive moment of a football match, the effervescence in the places of power and in the backrooms of culture… Portraits, demonstrations, often accompanied by the photographer’s commentary. True happiness to read and even to listen to their audacity, strokes of luck or fears. Xavier Lambours recounts his portrait of François Truffaut, strand of hair in the wind, with a frightened look (Cannes 1983) “At the time of this photo we did not know that he was sick. He had just learned that he was condemned. I believe that is what we see. He knew he was going to die. »

The photographers present at the opening talked about their memories (Raymond Depardon, Françoise Huguier, Xavier Lambours, Jean-Claude Coutausse, etc.) and at greater length at the end of the afternoon during a round table which brought together curators Lionel Charrier, Charlotte Rotman and Serge July. The photographers had come in large numbers to talk about their job, of their passion, their commitment for one of these moments which are part of the history of the Meetings. If Christian Caujolle was absent, his name, repeated at will, sounded like one of those tunes that stick in your head. “Libé is July but the photo in Libé is Caujolle”, even if they were never alone, even if they had brilliant successors. Journalist in the cultural service of Liberation, after a brief stint at the CNRS, he chronicled photography exhibitions and books from 1978 to 1981. Promoted head of the photo service, in charge of the daily’s photographic, editorial and visual policy, he was in favour of another kind of photography in the press which had little regard for the aesthetic qualities and was only interested in scoops for which it could invest considerable sums. Caujolle, had a clear editorial line, always reiterated: “We had convictions, among others, those of really considering the photographer as an author, of bringing together diversities of writing and looks and the strong desire to spread, at the international level in the press, and also in the cultural network, singular ways of questioning the world and shaping it . »

From the photographs of the exhibition, everyone will retain those that have moved, questioned, disturbed, amazed, softened or exasperated. Those he found like a brother in arms, those he had forgotten, those he discovered as an unexpected gift. That of Guillaume Herbaut taken at the Nation, April 29, 2002, while Jean-Marie Le Pen was a candidate in the second round of the presidential elections. “When I took the photo, I saw a lot of things. I saw two painting. I saw Liberty Leading the People by Delacroix and The Raft of the Medusa by Géricault. The representation of the Republic, in the process of sinking, and us still clinging to the raft. The photo made headlines a little later. “Or those of Bruno Boudjelal “employed by Liberation for a year to cross the African continent” offering a unique look at countries so close, so far. Or even the portrait of “Messerine on the run” (June 1979). Enemy number 1, by Alain Bizos or that of Orson Wells by Xavier Lambours (1982): “The Giant”.

I left the exhibition haunted by four photographs that show so little and say so much about the history of the world, the history of men. “Lip Vivra” (the striking workers in a watch making factory), August 4, 1976. Fotolib. A large affirmation “Vivra” suspended at the top of a tower, under the Lip brand logo, is a banner of struggles, hopes, utopias. And for Libé “the story that made France dream” while the newspaper was still at the heart of trade union struggles and published Les travailleurs de Lip : 53 photographies for the benefit of the strikers.

“Coup d’Etat in Mali”, March 26, 1991, by Françoise Huguier. “I saw the mothers who stood close to the brains of their children. She photographed the trail of blood from a body dragged on the floor of a morgue. Just a trace. Like a howl.

“Genocide of the Tutsis”, 1994, by Gilles Peress. In less than a hundred days, nearly a million people had been decimated in Rwanda. A pile of machetes, sharp steel blades tell of a country like an open-air cemetery. The silence of the dead.

“Paris Le Bataclan”, November 13, 2015 by Frédéric Stucin. A couple. One or the other, maybe the two of them, back from hell, hug each other. The life. Still, mostly. A premise of “You will not have my hatred” in the face of barbarism.

This is for the exhibition centered on essential photographs. The book, more complex, with the preface by Serge July, better shows the evolutions of Liberation. If the photographs are always outside the expected frames, outside the standards of journalistic information, they are well in line with the ideological and political life of the daily and its evolution from ultra-sectarian proletarian left to failing social democracy. This is an other story. That will be for a later text.

Françoise Denoyelle

50 ans dans l’œil de Libé

Curators : Lionel Charrier, Charlotte Rotman

Exhibition at l’abbaye de Montmajour

Until September 24 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

50 ans dans l’œil de Libé

Lionel Charrier, Charlotte Rotman

Preface by Serge July

Paris, Seuil, 2023, 335 pages, 39,90 Euros

https://www.seuil.com/ouvrage/50-ans-dans-l-oeil-de-liberation-charlotte-rotman/9782021510652