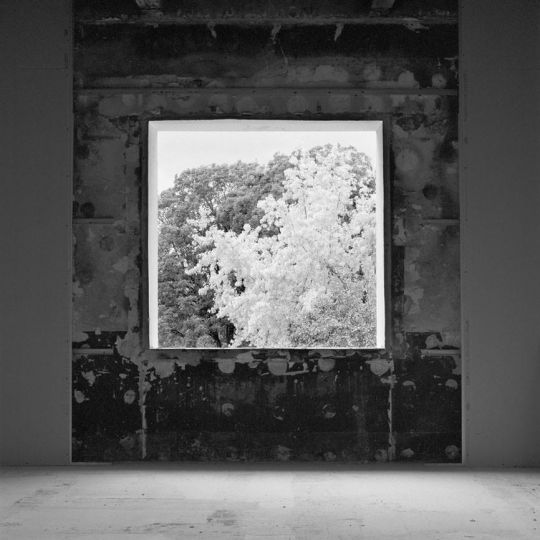

As a kid, Kirill Golovchenko spent a lot of time on the beach and most of the summer in a seaside holiday home. He took a swimming tyre and shot photos through it. The circular image this created reminded him of a ship’s porthole.

Summer. It’s hot. I’m six-years-old. The sea. It’s scorchingly hot. The sand burns your heels. This is the last summer of my carefree childhood. But I would learn that later.

I, my older brother Andriy, and our grandma Klava spent the whole summer living in Aunt Olia’s house near the Black Sea in Karolino-Buhaz. She was dad’s client and, if we were living in her house, probably indebted to us. Our parents stayed at home. They had to do the remodeling that was planned annually, the work for our good and the good of the fatherland.

We went to the sea every day. Andriy and I in front and Grandma bringing up the rear. We passed by the old military bunker. Partisans hid there during the war. They were heroes. But now the bunker reeks of shit and is covered in various cuss words that have been forbidden by grandma.

“Kirill, don’t go in there. You’ll get dirty again!” Grandma is strict; she used to be a teacher.

“Andriy, don’t read that nonsense!”

“What does ‘fuck’ mean?”

But grandma obviously doesn’t know what to say. She rolls her eyes and tries not to react. She even resorts to distractions: “Look! There are waves in the sea!”

We take the well-worn path down the almost vertical incline straight along the railroad tracks. They are impossible to avoid. We clamber over the tracks, sometimes at almost the same time that a train is barreling down them. We’re very scared, but we definitely want to slip across. After this, the sea is very near.

We get to the beach, to “our” place, even though the beach is public and as big as the Red Square. There are way too many people today. They probably bussed in vacationers. They’re white like seagulls and strangers to us.

“Grandma, should we keep going?”

“Who’s going anywhere?” our commander hesitates.

“Let’s go over there!” and I point to the left where we can see an enormous, sandy bald spot. “There’s a sandspit over there.”

“You can’t go onto the pit without your dad. You still can’t swim. There are deep, black pools near the shore over there,” Grandma retorts.

We always come to an agreement with her; of course there’s only one choice—it’s two against one. She gives in but the whole way keeps going on about how she’s afraid of falling in a black hole. She’s making my head hurt.

We finally get to the new spot and lay out our blanket. At the water’s edge we use our hands to dig a pit and carry wet sand in our cupped palms onto the beach. We build a big fort surrounded by a moat and pour the runny sand into it.

Grandma decides to stick her nose in our work, “Don’t dig so deep—the sea’s small enough without you!”

“Grandma, when will the rainfall come?” Andriy asks looking at the sky. He’s finished first grade and already way too smart.

“Who knows? This summer it only rains on TV.”

Time passes and the sun moves to noon. It’s stopped and not moving at all. It’s barbecuing us. The work and the heat take their toll; we want to swim and we want to eat. Grandma sticks an umbrella in the sand and realizes after she digs around in our things for a while that she forgot our food at the apartment. Andriy will run home to get it. He’s older. He immediately agrees because he also forgot his pail and shovel. Just like before, she instructs him to look both ways before crossing the tracks.

It’s hard to build a fort without an assistant. I look out at the sea toward the black pools. They’re right up near the shore. Dad said they’re dangerous and can suck you in. I walk along the beach past the holes. What if I tried to go in the water? I’d be able to tell Andriy about it. Grandma’s asleep under the umbrella with a book protecting her face from the sun.

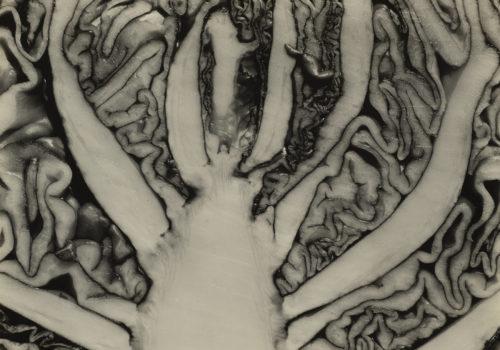

The pool is dark. Scary. What if it suddenly sucks me in? I take my first step near the shore and step into sand that’s loose like straw. Another step and along the steep edge the earth slips away from under my feet and like lightning I’m up to my chest in water. I want to shout, but the water’s already up to my nose. Quickly inhaling whatever air’s left, I find myself under water. I try to back away, but I’m just slipping deeper into the black hole. I stand motionless. Yet I’m still sliding down. In a panic, I exhale all my air.

That’s it… The end… I can already see that I’ve drowned, but I still don’t know what happens next. My life doesn’t flash before my eyes in bright pictures. For a second I mourn the chocolate Hryliazh candies carefully hidden away in my satchel; my brother will probably get them. My mouth opens automatically and I gulp water. My life is sinking into a dark abyss of soft seaweed. It wraps around my legs. I throw back my head and see the green surface of the water. I’m fading… Delirious, I see Grandma and me on the bench near the house. She shouts:

“Kirill, don’t crack sunflower seeds onto the floor. Then I have to clean them up!”

I frantically kick my legs and suddenly…I’m out of the hole. I don’t know how. It was probably me. I climb out. I raise myself up a bit. I get sick. I can see our umbrella. I crawl over and plunk myself down near Grandma. “Oh, honey, I dozed off…,” she slowly opens her eyes.

I sluggishly come to. I look around. There’s not a soul on the beach besides us. That means there was no one to save me. How did I get out? Maybe I floated up like a turd. Or have I learned how to swim?! I really want to tell her, but if Grandma finds out, she’ll forbid me from even looking at the sea!

When Dad came, he was surprised to see that I could already float. And in the fall, on September 2, my parents gave me a gift: I went into the great swimming unknown school. By then I had eaten the chocolate Hryliazh in my satchel. I went unprepared, not knowing exactly how to read or write.

Kirill Golovchenko

Kirill Golovchenko, Out of the Blue

Published by Rodovid Press

30€