If you love photography, it’s highly likely you know—and love—Magnum, the legendary photo cooperative co-founded by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger, and Chim (David Seymour) in 1947. But what really is Magnum, exactly? And what has it been trying to do all these years anyway?

These fundamental questions are central to “Magnum Manifesto,” a co-production between the International Center for Photography, in New York, and Magnum Photos on the occasion of the cooperative’s 70th anniversary. The answers, of course, are complicated.

That’s perhaps most evident in the “epilogue” for the show, a slideshow of photos set to Bach’s Goldberg Variations interspersed with quotes by Magnum members describing their understanding of Magnum’s values and mission. “Magnum is not a capitalist business,” Inge Bondi says in one slide. In another, Elliott Erwitt directly contradicts that view. “Magnum…is a business,” he says. Later, Burk Uzzle says, “Magnum is a divided, chaotic organization, with little or no idea of what it wants to be about, no idea of what the future might be.” Chris Steele-Perkins then offers the opposite view. “There is somehow this, even in the broad church that Magnum is, this collective sense of we’re swimming in the same direction.”

These tensions— the individual versus the collective, the radical versus the traditional— play out time and again in “Magnum Manifesto.” Rather than pick just one lens through which to view the cooperative, Clément Chéroux, Clara Bouveresse and ICP Associate Curator Pauline Vermare have chosen instead to hold all these contradictions up for examination, to present Magnum, as John G. Morris described it, as a “paradox,” and an “utterly impossible concept in the history of journalism.”

The result is, nonetheless, surprisingly cohesive. Chéroux, Vermare and Bouveresse have combed through decades of history, thousands of images, and wildly differing artistic visions, and come up with a narrative that probes and challenges, but manages not to confuse or overwhelm. If visitors leave with any single takeaway it’s that, when it comes to Magnum, single takeaways aren’t possible.

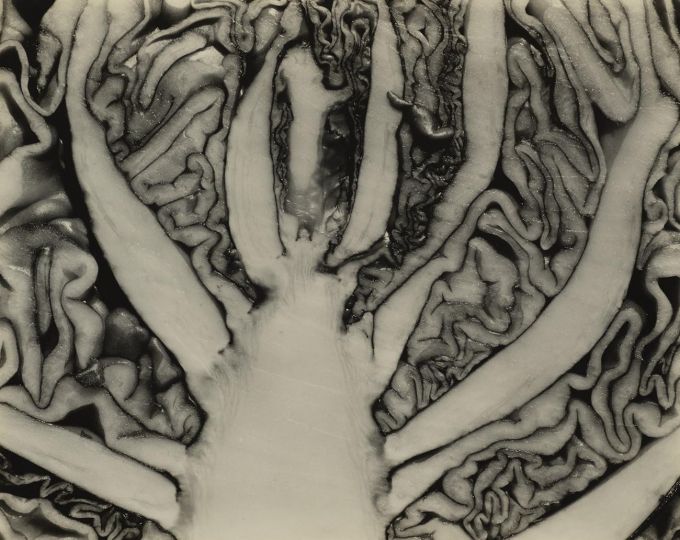

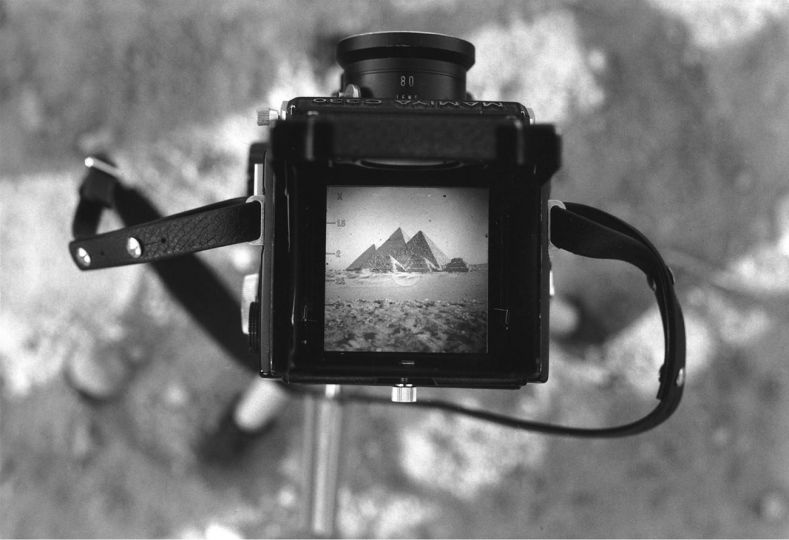

The exhibit is organized in three parts according to chronology and theme. The first, “Human Rights and Wrongs,” focuses on Magnum’s early years, and frames its members’ work under the umbrella of “universality,” a concept echoed in the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This section opens with a wall shared by a single photo from all of Magnum’s members, and continues with individual projects, like Paul Fusco’s “RFK Funeral Train,” that focus on the ties that bind disparate groups and people.

“It wasn’t just a collective of individuals; it was a group,” Chéroux said during a tour of the exhibition for journalists.

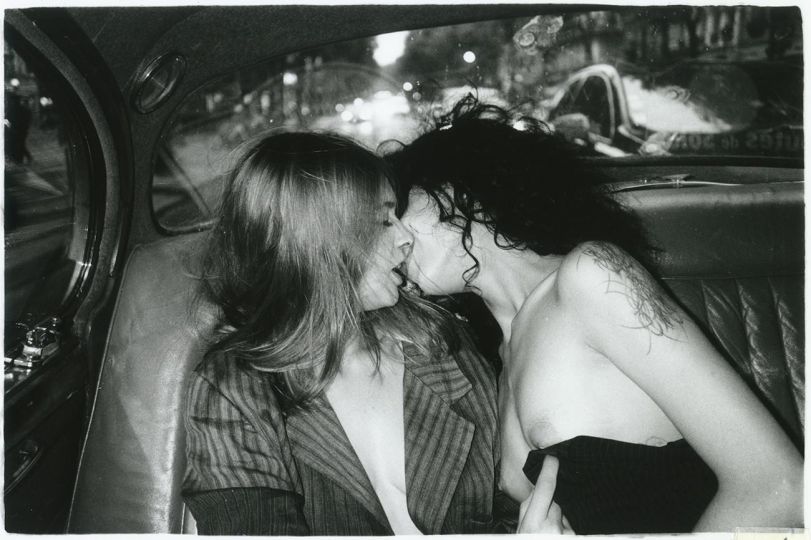

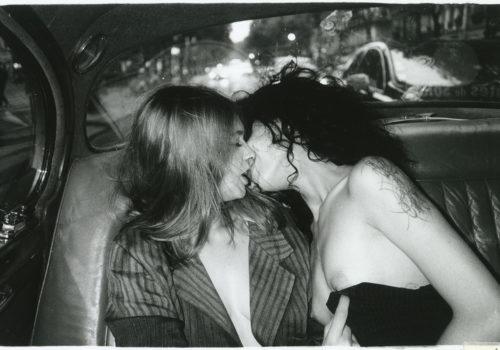

The spirit of the next section in the exhibit, “An Inventory of Differences,” varies vastly from the first. Rather than focus on Magnum’s humanist impulses, it shows the cooperative’s interest in “otherness.” Here, we see Danny Lyon’s 1967 photographs of inmates in Texas that capture, according to wall text, the “sheer hopelessness of prison life.” We also see photos from Jim Goldberg’s Rich and Poor, a project highlighting the differences between San Francisco’s wealthiest and underprivileged.

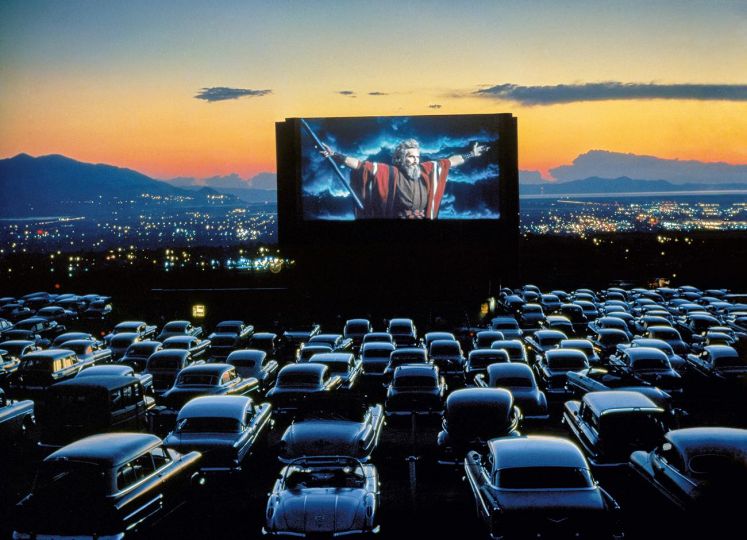

There are two “intermission” segments in the exhibit, and they are both fascinating. The first, positioned between the first and second section of the exhibition, features an interactive slot machine. When visitors pull the crank, it triggers a projection of three images, which roughly fit the theme of the collapse of the American dream, chosen at random. Downstairs, just before the third part of the exhibition begins, there’s a wall dedicated to work made by Magnum photographers for the annual reports of private companies. Reconciling this work with Magnum’s renegade, radical reputation is a head-scratcher.

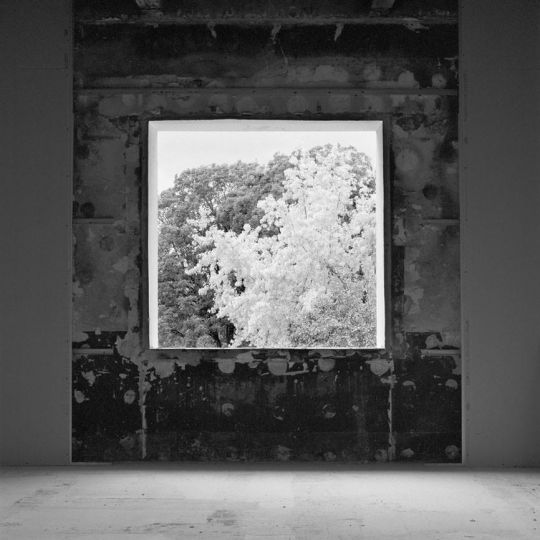

The third section, “Stories About Endings,” showcases works by current Magnum photographers. Their unifying theme is, as the title suggests, the end of things. This includes large concepts like colonialism and communism and specific practices like traditional fishing and the Concorde airliner. Highlights include Mark Power’s photos of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Jerome Sessini’s photos of the mourning of Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, and portraits of Taliban soldiers collected by Thomas Dworzak.

Where does Magnum go from here? It could go anywhere and everywhere, which is really what it’s been doing all along, if this exhibition’s thesis is correct. A quote from Lee Jones in the aforementioned epilogue sums it up nicely: “Magnum is, and should fight to remain, an anachronism.”

Jordan Teicher

Jordan G. Teicher is an American journalist and critic based in Brooklyn, New York.

Magnum Manifesto

May 26, 2017 – Sep 03, 2017

International Center of Photography

250 Bowery

New York, NY 10012

USA